Introduction to Modeling with MapleSim

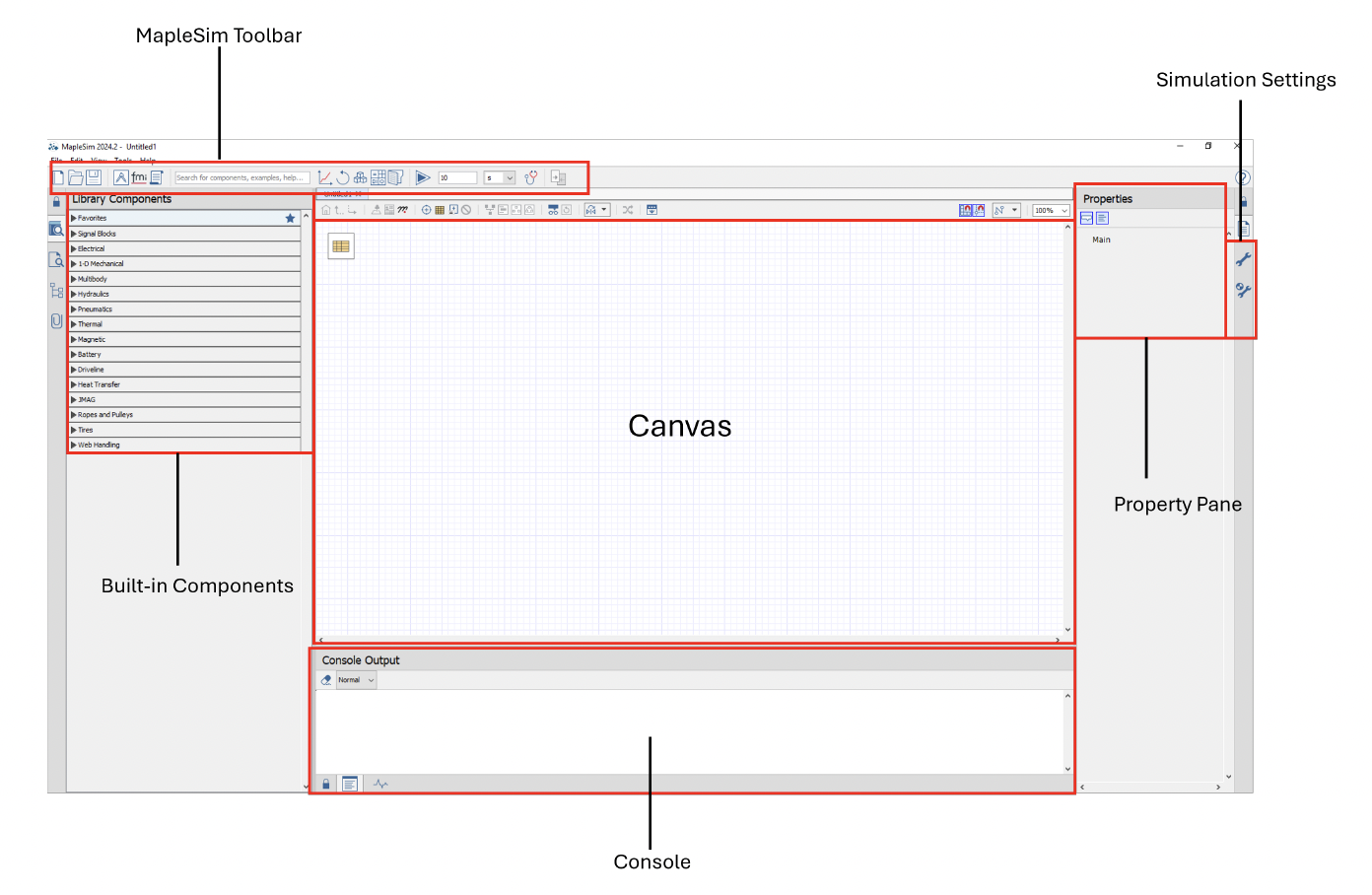

MapleSim is a multidomain system-level modeling and simulation tool that enables users to perform dynamic simulations across various domains using built-in libraries. These domain’s include Web Handling, Electrical, Multibody, Hydraulics, Pneumatics, and more. To build dynamic models in MapleSim, users must first become familiar with the environment. This chapter focuses on understanding the MapleSim interface, constructing a simple model using library components, exploring key features for model setup, and running simulations.

In this section, we will explore the MapleSim interface and gain a comprehensive understanding of the various features and functionalities available to users. To begin with we will discuss on the different modeling components, parameter configurations, and simulation settings that are essential for constructing a well-defined system model.Furthermore, we will explore options such as configuring solver settings, and modifying the simulation parameters for better performance.

Finally, we will dwelve into the post-processing capabilities of MapleSim which includes looking into our Result manager window where a user can look at the results such as plots/3D model to gain valuable insights into their system’s behavior and refine their models accordingly if need be.

Figure 1.1: MapleSim Interface

The MapleSim canvas serves as the primary workspace within the tool, allowing users to drag and drop components from the library to construct their models. The placement of components on the canvas is purely for visual organization and does not influence the actual simulation.

While users have the flexibility to position components anywhere within the canvas, the physical behavior of the model is determined by the connections between components and the port information. These connections define how different elements interact and ultimately influence the simulation results.

MapleSim’s component library contains more than hundreds of pre-built components that can be used to build models. These components are catogorized into different domains making it easier to navigate and quick selection of the most suitable components for a given application. Furthermore, users are not restricted to the built-in components available in the library. MapleSim provides the flexibility to create custom components, enabling users to tailor models to their specific needs. This capability will be explored in detail in a later session.

MapleSim toolbar provides a range of essential tools that can help the user with their modeling workflow. It allows users to:

Run simulations to test and analyze their models.

View and interpret simulation results through built-in result manager window.

Perform reruns to refine model performance and troubleshoot issues

Import external files, such as CAD models and Functional Mock-up Units (FMUs), to integrate with existing designs

Open a Maple worksheet enabling advanced custom post-processing.

Access built-in applications that provide additional functionalities to enhance model development and post-processing.

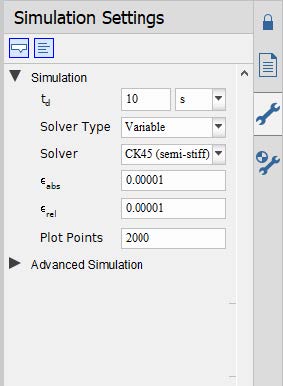

The simulation settings provide users with the ability to configure various aspects of their model setup.

Figure 1.2: Simulation Settings

These settings allow users to:

Adjust the simulation duration to match the requirements of their analysis.

Select the most appropriate solver type based on the specific application needs.

Define the minimum number of data points to be plotted for accurate result visualization.

Import external files, such as CAD models and Functional Mock-up Units (FMUs), to integrate with existing designs

Set error tolerances to ensure numerical stability and precision in the results.

The Advanced Settings provide additional configuration options for a more detailed model setup

The Console Output presents progress messages that reflect the status of the MapleSim engine during simulation. Additionally, it provides details on model failures and warnings, helping users diagnose and troubleshoot issues effectively.

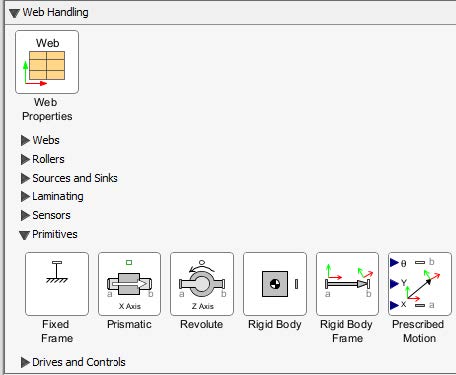

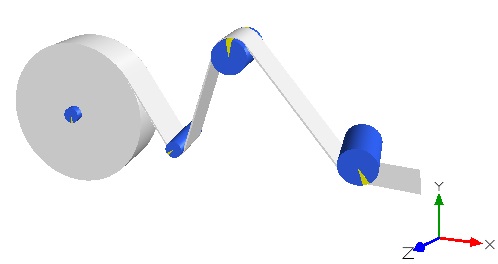

In this section, we will walk through the process of building a planar double-pendulum model in MapleSim, utilizing the primitives section of the Web Handling Library. The goal of this chapter is to guide the user in creating a simple model by effectively using the interface options discussed in the previous sections. While we will focus on the basic implementation of the model here, a more in-depth introduction to the components from the Web Handling Library will be provided in a subsequent chapter. The primitives section of the Web Handling (WH) Library consists of specialized multibody-based components designed to accurately position the web handling elements within a model. These components, much like the other elements found in the Web Handling Library, are restricted to a two-dimensional plane, specifically the x-y plane.

Figure 1.3: Primitives section-WH Library

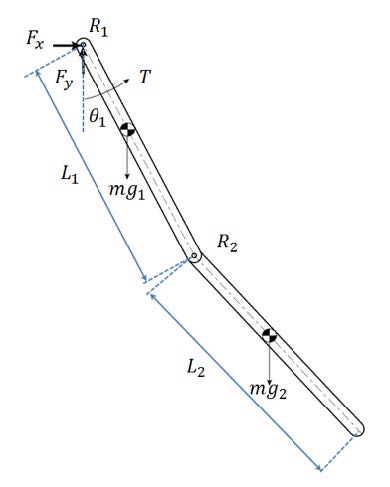

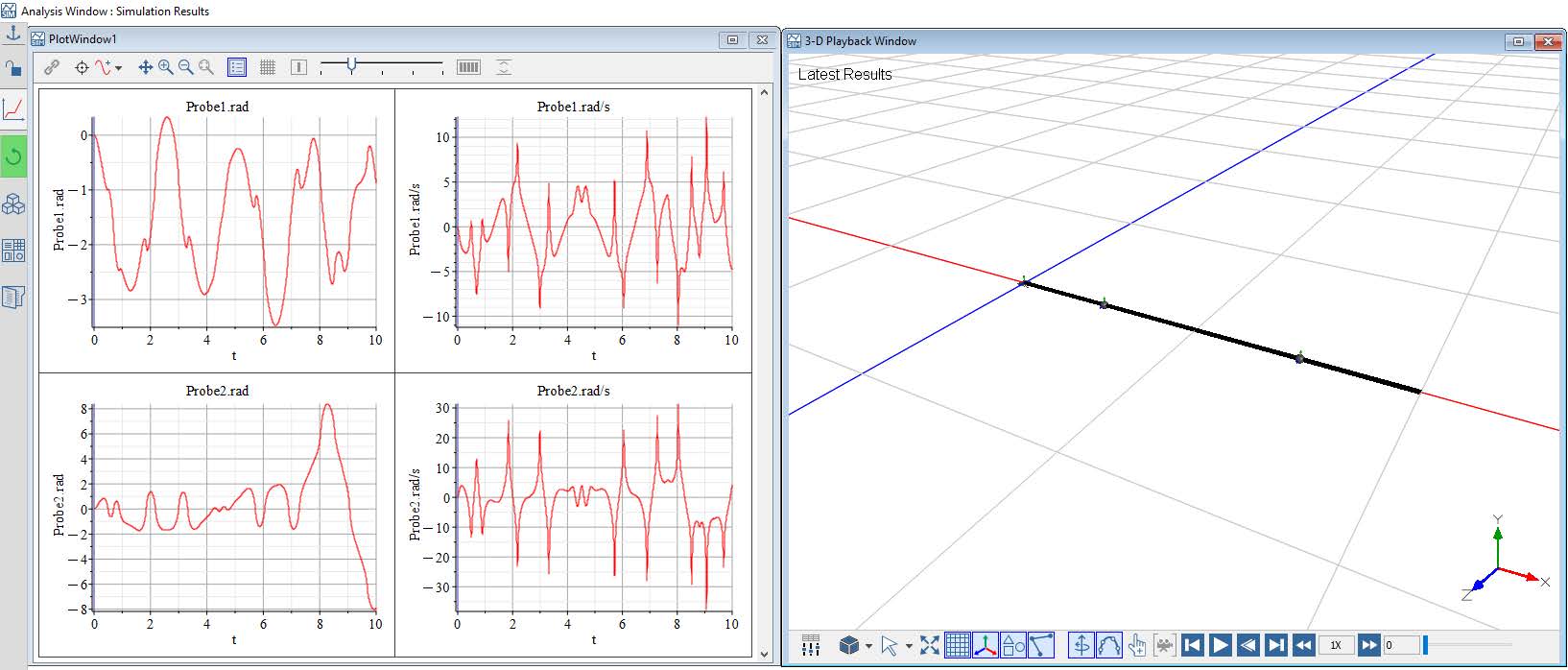

The schematic of a double pendulum model is shown below:

Figure 1.4: Double pendulum mechanism

This model consists of a revolute joint, R1, which is attached to the first planar link. This planar link is attached to the second planar link through a second revolute joint, R2. For the system shown in the diagram, gravity is assumed to be the only external force, acting along the negative y-axis.

However, it is advisable to follow the steps below to construct the model from scratch. The figure below provides an overview of the model that will be built in this section:

Figure 1.5: Double Pendulum Model

Use the following steps to create the model in MapleSim:

Open a new MapleSim document and save it as “Double_Pendulum.msim”

Under the Libraries tab, browse to the Web Handling > Primitives menu, and then add two Rigid Body Frame components and a Rigid Body component.

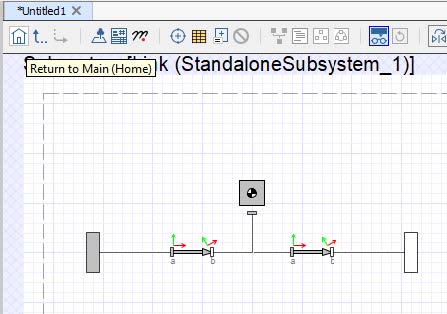

Drag the components in the arrangement shown below and connect the components together by drawing connection lines between the RB and RBF components.

Figure 1.6: Creating a linkage in MapleSim

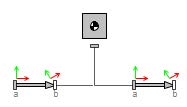

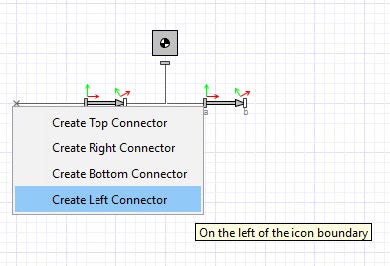

Select all the three components and right-click. From the context menu, select ‘Create Subsystem’. In the subsystem dialog box, enter ‘Link’, and then click ‘OK’.

Figure 1.7: Connecting component to subsystem boundary

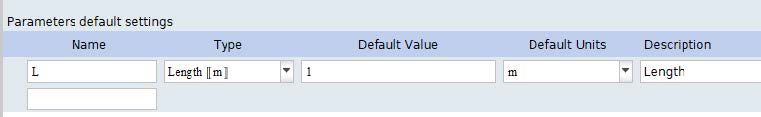

In this task, you will define a subsystem parameter, L, to represent the length of the link and assign the parameter value as a variable to the parameters of the Rigid Body Frame components. The Rigid Body Frame components will then inherit the numeric value of L.

To define and assign parameters:

Double-click on the ‘Parameters View’ (![]() ) to display the subsystem default settings. In the first row, define a parameter called L and press ‘Enter’. Specify ‘Length’ for ‘Type’, 1 for ‘Default Value’, ‘m’ for ‘Default Units’, and ‘Length’ for ‘Description’ as follows:

) to display the subsystem default settings. In the first row, define a parameter called L and press ‘Enter’. Specify ‘Length’ for ‘Type’, 1 for ‘Default Value’, ‘m’ for ‘Default Units’, and ‘Length’ for ‘Description’ as follows:

Figure 1.8: Define Link parameters

Click ‘Diagram View’ (![]() ) in the Navigation Toolbar to go back to the diagram view.

) in the Navigation Toolbar to go back to the diagram view.

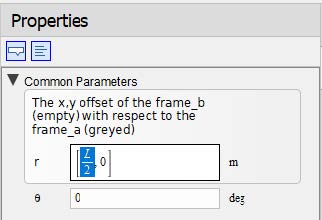

Select both of the Rigid Body Frames simultaneously by pressing ‘Ctrl’ and then selecting each of the components. Specify the common parameter ˜r to be [L/2, 0, 0] [m].

Figure 1.9: Define common parameters

Click ‘Return to Main’ (![]() ) located in the top left corner in the Navigation Toolbar to go back to the main level of the model.

) located in the top left corner in the Navigation Toolbar to go back to the main level of the model.

Figure 1.10: Return to Home

To create the double pendulum mechanism, follow these steps:

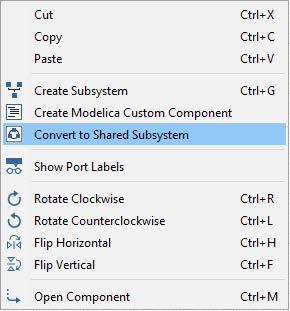

Right-click on the Link subsystem and select ‘Convert to a Shared Subsystem’

Figure 1.11: Right-click menu

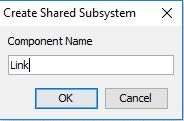

Enter ‘Link’ in the pop-up menu:

Figure 1.12: Enter the name for the shared subsystem

Click ‘OK’.

Under the ‘Library Components’ tab (![]() ), drag a Fixed Frame component and a Revolute from Web Handling > Primitives menu.

), drag a Fixed Frame component and a Revolute from Web Handling > Primitives menu.

Click the subsystem Link2 , enter 2 for the parameter L.

Connect the components and subsystems together as shown in the following diagram:

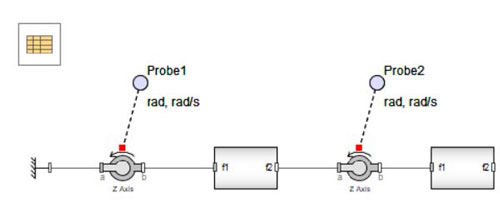

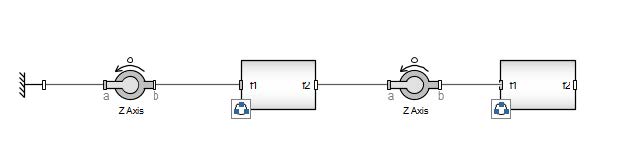

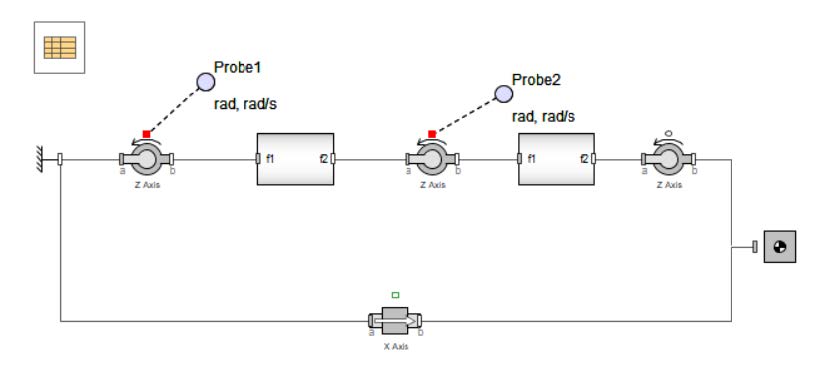

Figure 1.13: Double Pendulum

To simulate the model and observe the simulation results:

From the Model Workspace Toolbar, click ‘Attach Probe’ (![]() ).

).

Figure 1.14: Adding probes

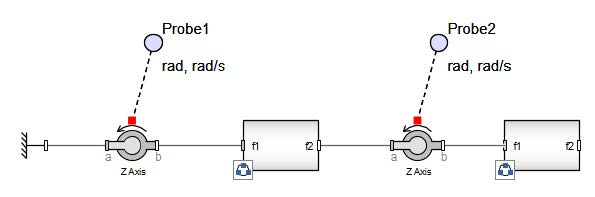

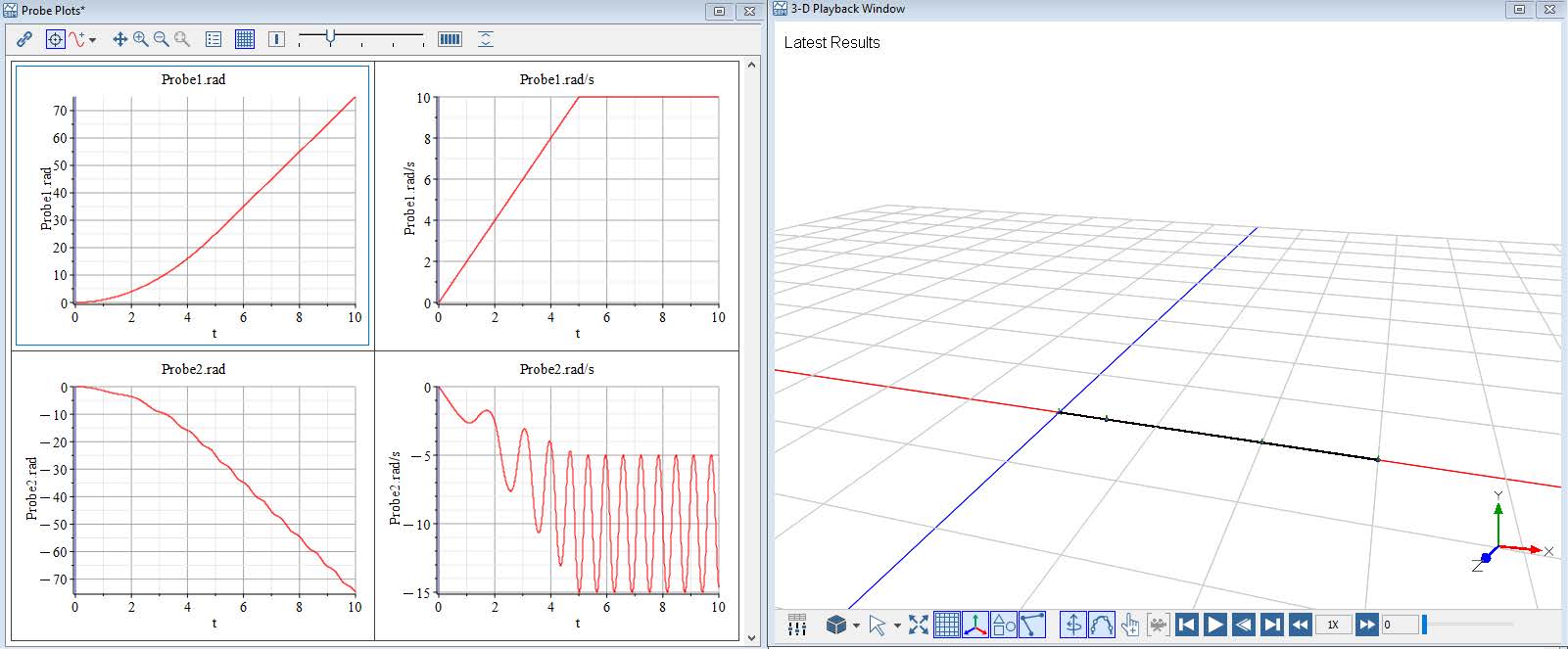

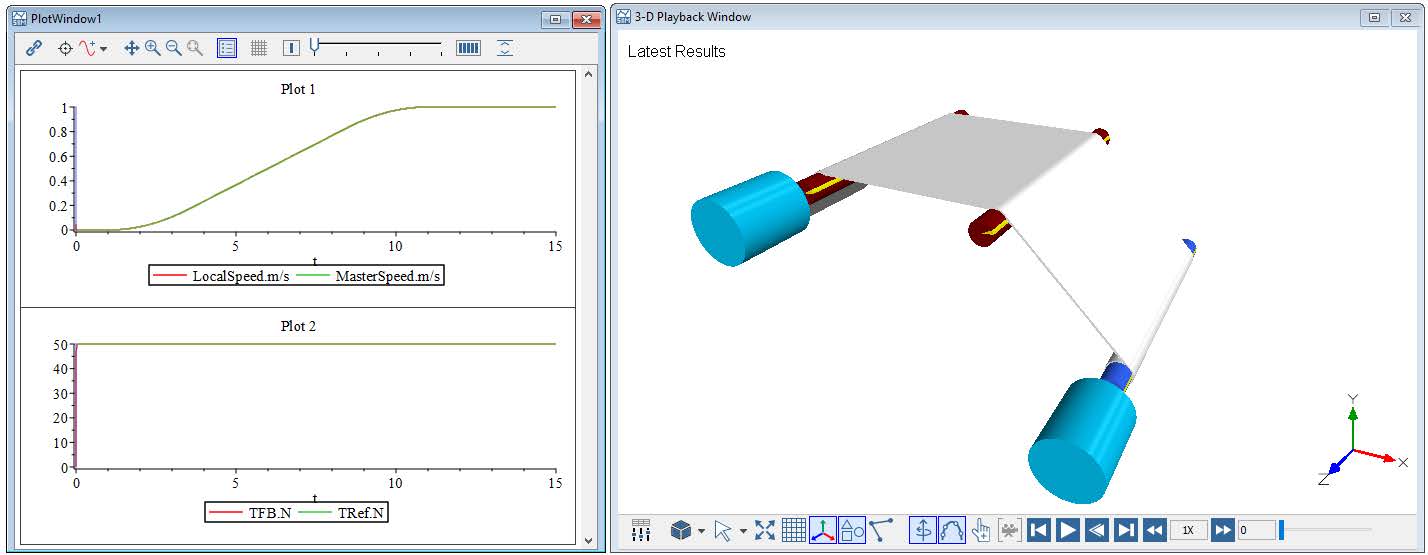

Click ‘Run Simulation’ (![]() ) in the Main Toolbar (or hit ‘F5’). When the simulation is complete, the following plots appear:

) in the Main Toolbar (or hit ‘F5’). When the simulation is complete, the following plots appear:

Figure 1.15: Simulation results

Click ‘Play’ (![]() ) in the 3-D Playback Window to see an animation of the simulation results.

) in the 3-D Playback Window to see an animation of the simulation results.

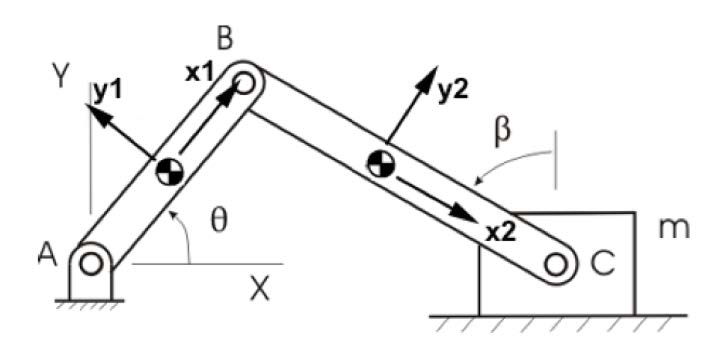

Using components from the Multibody mechanical library, you will model the planar slider-crank mechanism shown in the following figure:

Figure 1.16: Planar slider-crank mechanism

However, it is advisable to follow the steps below to construct the model.

The figure below provides an overview of the model that will be built in this section:

Figure 1.17: Slider Crank Model

The slider-crank mechanism can be created by expanding the double-pendulum example created in the previous section.

Open the “Double_Pendulum.msim” model from the previous section and save it as “Slider_Crank.msim”.

Drag a Rigid Body , a Revolute and a Prismatic component from the Web Handling > Primitives menu.

Connect the components together using the above arrangement.

Click ‘Run Simulation’ (![]() ) in the Main Toolbar (or hit ‘F5’). When the simulation is complete, the following plots appear:

) in the Main Toolbar (or hit ‘F5’). When the simulation is complete, the following plots appear:

Figure 1.18: Unactuated Slider Crank

This simulation shows the results of an actuation slider crank mechanism. Now lets add an actuation to the model.

In this section, we will introduce a basic actuation mechanism to the model by briefly exploring the 1D Mechanical Library in MapleSim. This will provide an initial understanding of how actuation can be implemented within the system. While this section offers a quick overview, a more in-depth exploration of actuation techniques, control strategies, and their impact on system behavior will be covered in the upcoming sections.

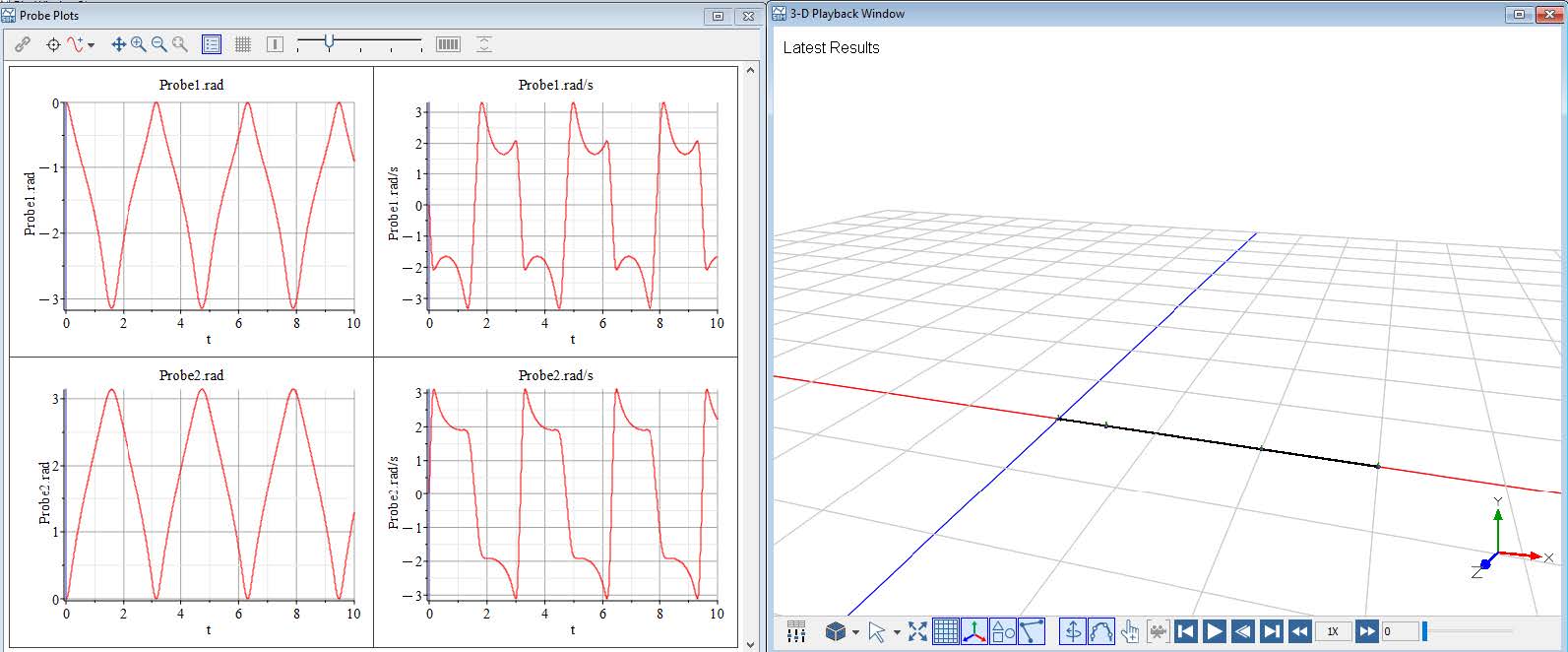

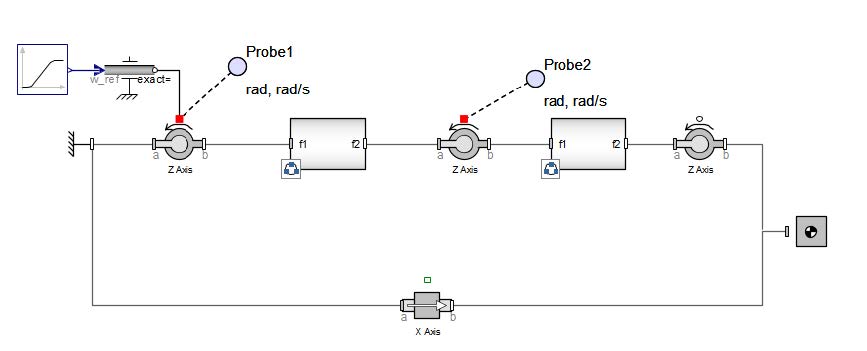

The figure below provides an overview of the model that will be built in this section:

Figure 1.19: Actuated Slider Crank Mechanism

Drag a Rotational Speed component from 1-D Mechanical > Motion Drivers menu. This component enerates a forced angular speed according to the input signal its connected to.

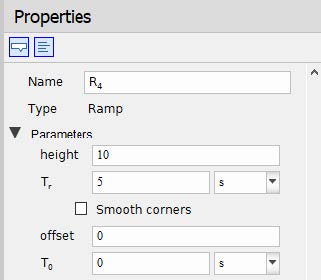

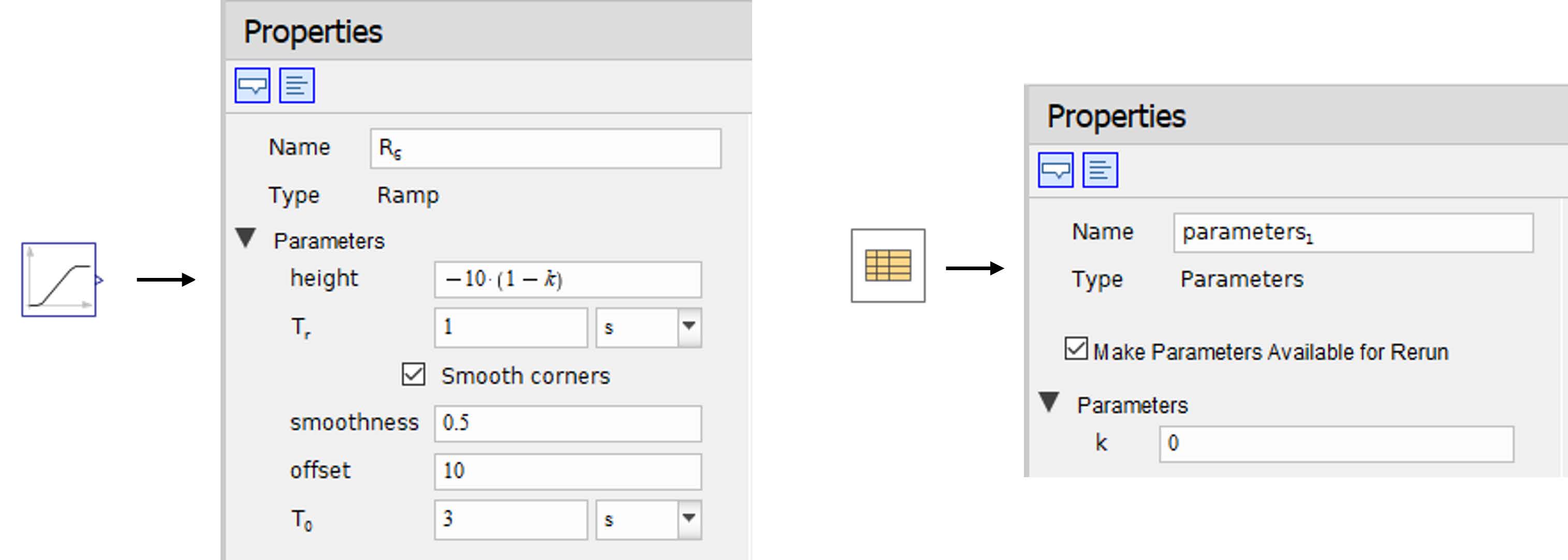

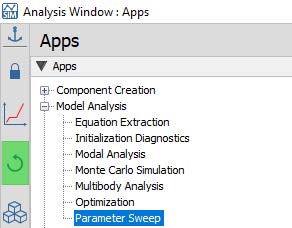

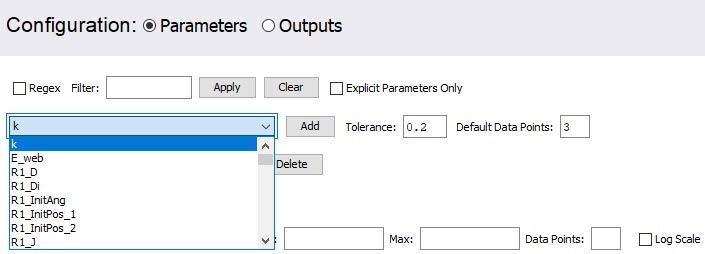

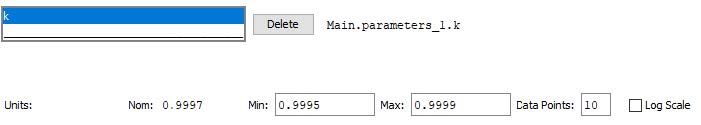

For the input signal, we are going to bring in a Ramp component from Signal Blocks > Common menu.

Use the following settings for the Ramp component.

Figure 1.20: Ramp parameters

Make the connection as shown in the above.

Click ‘Run Simulation’ (![]() ) in the Main Toolbar (or hit ‘F5’). When the simulation is complete, the following plots appear:

) in the Main Toolbar (or hit ‘F5’). When the simulation is complete, the following plots appear:

Figure 1.21: Actuated Slider Crank Results

Press the simulation play back button to visualize the simulation.

The Primitives subsection of the Web Handling Library which is used to build simple planar mechanism in this chapter is actually a subset of a much elaborate Multibody Library in MapleSim. If interested one can look into the Multibody Library which is specifically created to model 3-D multibody mechanical systems in MapleSim.

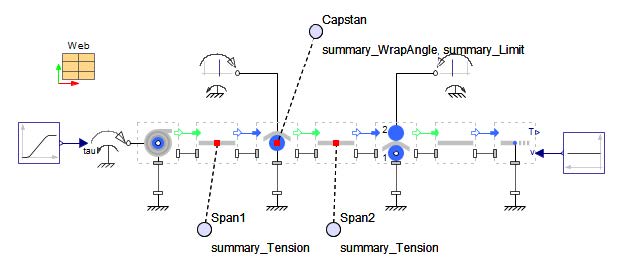

Introduction to Web Handling Library

Let us take a moment to briefly discuss the various components available within the Web Handling Library. Compared to other libraries in the tool, the Web Handling Library offers a more straightforward and intuitive experience for users, particularly when it comes to building and understanding system models. One of the key reasons for its user-friendliness is its planar modeling approach, which restricts the system to two dimensions—making it easier to visualize and comprehend. Additionally, the components in this library come with clear visual representations and built-in animations, which help users quickly grasp the physical behavior of the system and validate model functionality in a more interactive manner. Lets now look into the major categories of the library.

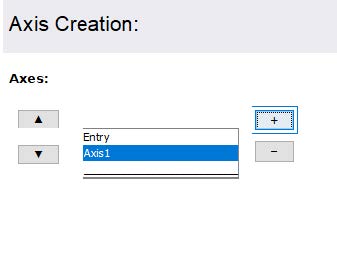

Lets look into the various sub-categories of the library components.

Web Properties

Webs

Rollers

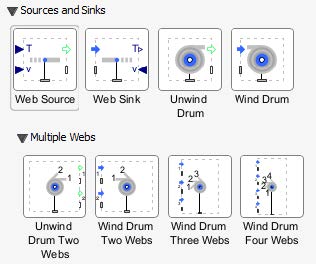

Sources and Sinks

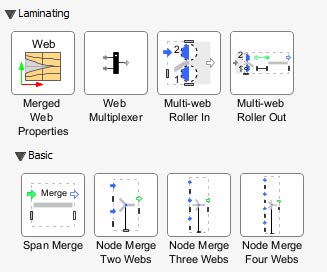

Laminating

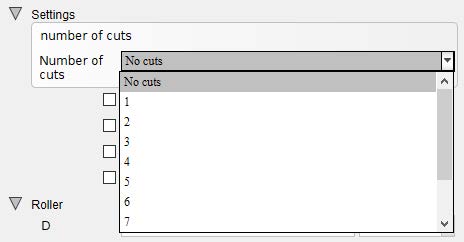

Slitting

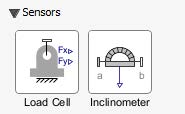

Sensors

Primitives

Routing

Drives and Controls

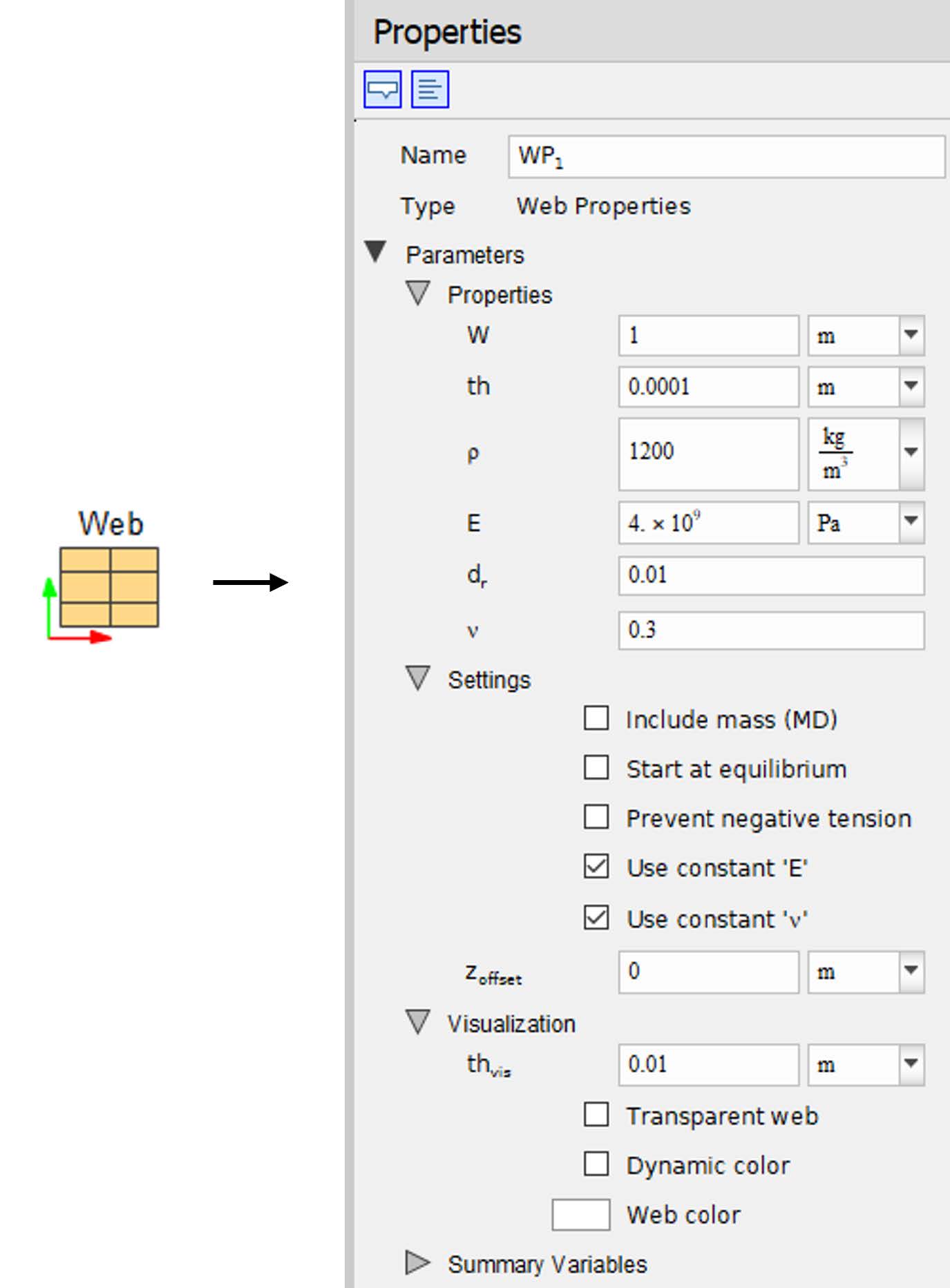

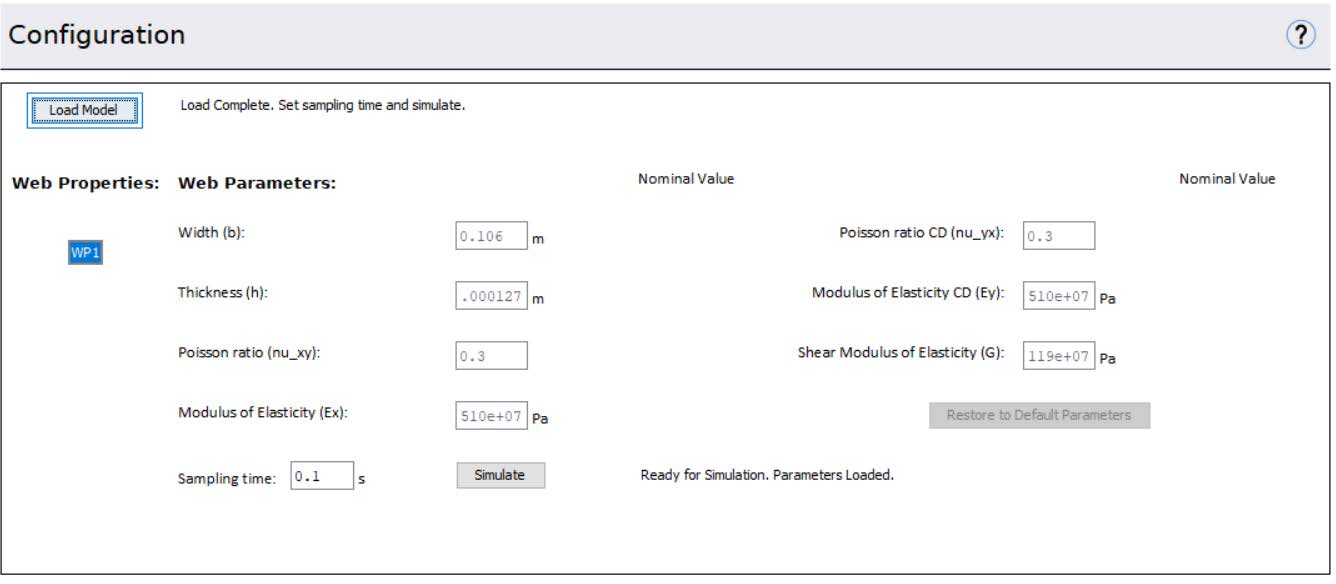

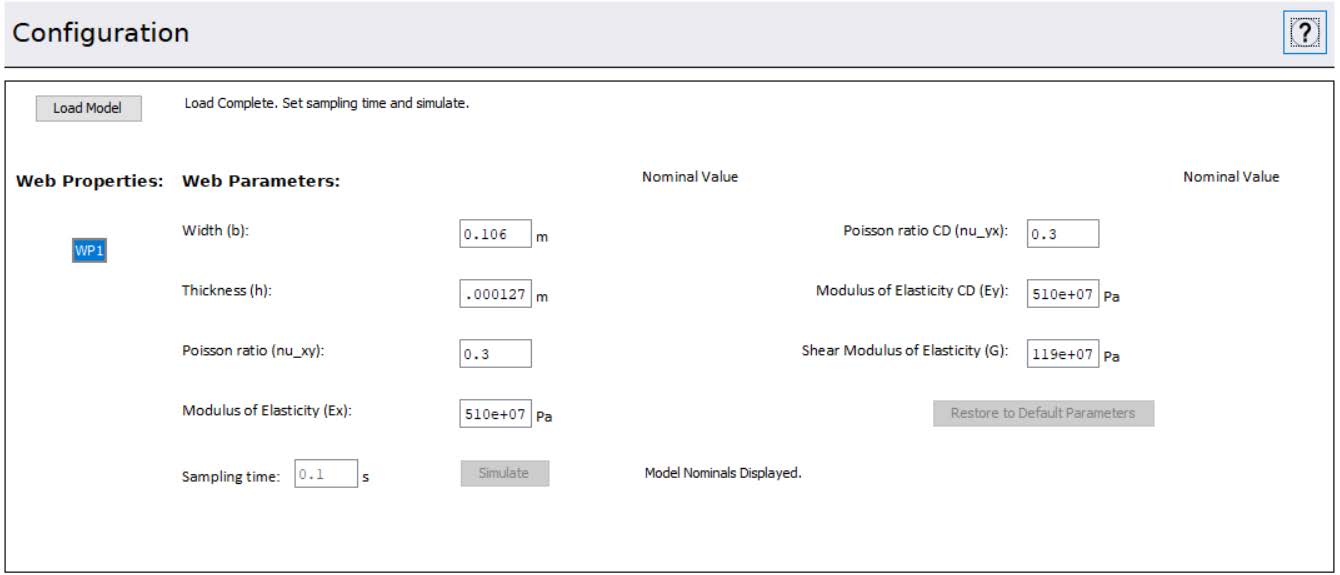

The Web Properties block allows users to define the mechanical and physical characteristics of the web material used in their model. This includes essential parameters such as width, thickness, density, Young’s modulus (elastic modulus), and Poisson’s ratio—all of which directly influence the dynamic behavior of the web during operation.

In addition to the mechanical properties, this block also enables users to configure the visualization settings for the web, allowing for clearer and more informative animations during simulation. This block is a record where the properties automatically apply to all components located at the same hierarchical level or within any subsystems below it. Moreover, each components from the library includes a field to reference a specific Web Property block. This allows models to incorporate multiple web types by assigning the appropriate Web Property block to each corresponding component.

Figure 2.1: Web Property Block

Nonlinear Material - Variable Modulus of Elastisity - When the Use constant ’E’ option is unselected, new parameters are enabled to define the modulus of elasticity as a function of strain via a lookup table.

Nonlinear Material - Variable Poisson’s Ratio - When the Use constant "’nu’"option is unselected, new parameters are enabled to define the Poisson’s ratio as a function of strain via a lookup table.

Include Mass (Machine Direction) - When the Include Mass (MD) option is selected, all spans in the model activate a second equation for the conservation of momentum.

Start at Equilibrium - When the Start at Equilibrium option is selected, upstream and downstream strain values are set to equal at initialization. In most case this results in the model starting with the web line initialized to the same tension as set at the source.

Prevent Negative Tension - When the Prevent negative tension option is selected, the stress in the span is prevented from becoming negative, however, strain can still become negative to approximately represent web accumulation. For more accurate modeling of such scenarios, use a Sagging Span component.

Visualization - When the Dynamic color option is selected, the user has the choice to have the span (and roller contact arcs) change color based on tension, velocity, width, or strain. When the web speed option is selected, the user has a choice to apply color to roller surfaces as well. This option can highlight large roller slippage.

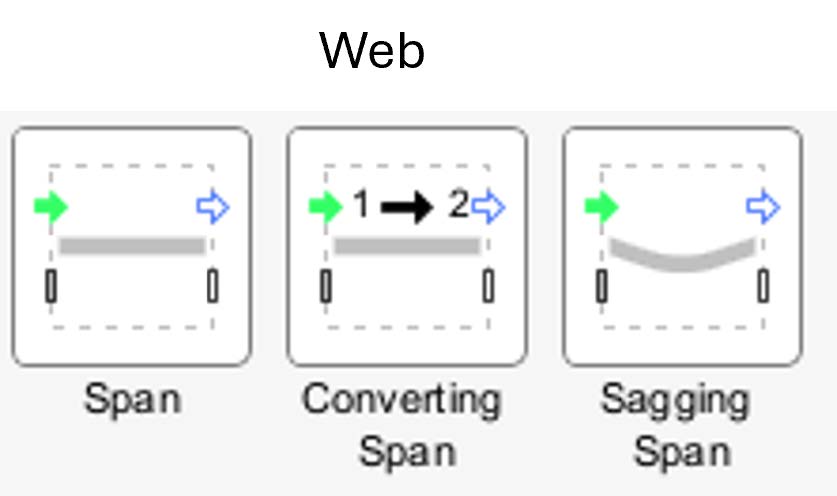

The Web subsection is specifically designed to model the web material and its behavior within the system. The components under this section represents the physical properties of the web spans crucial in determining how the web behaves dynamically as it moves through the system. This section contains the following components;

Figure 2.2: Web spans

Span - This component is used to represent the viscoelastic behavior of the web material as it moves through the system.

Converting Span - This component is used to represent a transition zone where the web material properties change from one type to another.

Sagging Span - This component is used to simulate the influence of gravity on the web span. It captures the sagging behavior that occurs when the web hangs between two rollers under its own weight.

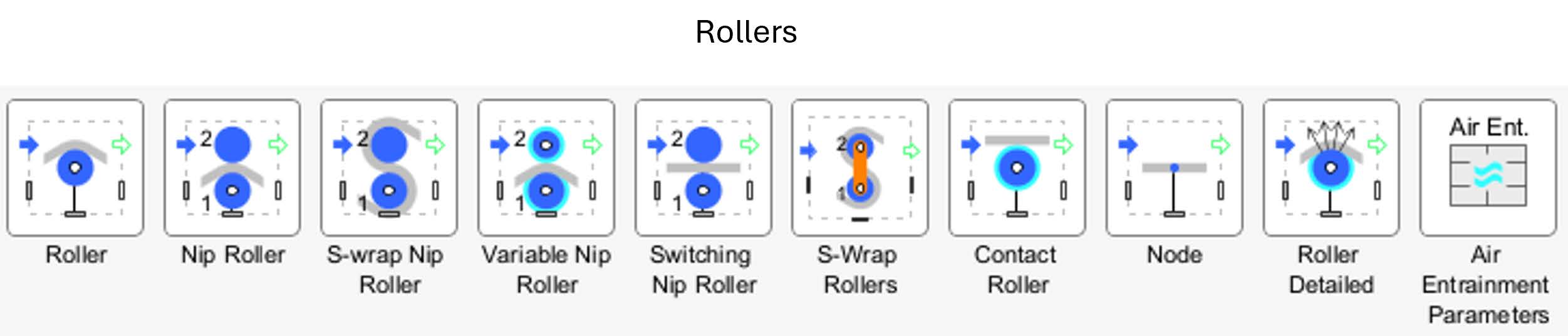

Rollers are essential components that guide and support the web material as it travels through the system, playing a crucial role in roll-to-roll (R2R) processes. The Web Handling Library offers a comprehensive selection of roller components, enabling users to accurately model the mechanical behavior and dynamics of their systems. This section includes;

Figure 2.3: Rollers

Roller - The Roller component is used to represent either a pull roller or an idler roller within the system.

Nip Roller - This component is designed to capture the interaction between a pair of rollers, more specifically a nip roller and a companion rollers. The key distinction of this component from a regular roller is the inclusion of additional dynamics—specifically, the combined inertia and bearing friction from both rollers in the pair. This added complexity allows for a more accurate representation of systems where the interaction between two rotating bodies influences the web’s motion and tension characteristics.

S-wrap Nip Roller - This component simulates a pair of rollers—a nip and a roller—through which the web is guided, wrapping around and passing between them in an S-shaped path

Variable Nip Roller - This component is designed to simulate a system consisting of two rollers: one represents the nip, where the material is pressed between the rollers, and the other functions as the roller that interacts with the nip.

Switching Nip Roller - This component is designed to simulate a pair of interacting rollers—specifically, a nip and a companion roller. While it shares similarities with the standard Nip Roller component in its basic structure, it introduces a key functional difference: the ability to dynamically switch the upstream and downstream web spans between the two rollers over the course of the simulation.

S-wrap Roller - The S-Wrap Rollers component simulates a pair of pull rollers arranged in an S-Wrap configuration, where the web material follows an S-shaped path as it wraps around the rollers.

Contact Roller - The Contact Roller component represents a single roller that has the ability to either engage with or disengage from the web during operation.

Node - This component simulates an ideal roller with zero radius. It represents an idealized point that enables interaction with or manipulation of the web from one side to the other without affecting dimensions, sizes, wrap angles, or other geometric properties. It is particularly useful for simplified, abstract analyses.

Roller Detailed - Slippage within a model can significantly impact the performance of a roll-to-roll (R2R) system. This component represents a pull roller that incorporates the effects of slippage between the roller surface and the web

Air Entrainment - This component stores the parameters that define the impact of air entrainment on a roller.

This section contains the components that define the boundary conditions of a roll-to-roll (R2R) model. In many cases, it is not necessary to model the entire system, but instead, it is more efficient to focus on a specific portion of the web line that is of particular interest. This approach can significantly reduce modeling time and complexity. The components in this section provide the means to set the boundaries for such a model, enabling the user to define the limits of the system being analyzed while maintaining the accuracy of the simulation for the selected region.

Figure 2.4: Sources and Sinks

Web Source - This component models an ideal web source with either a Speed and Tension input or by just specifying Tension alone.

Web Sink - This component represents an ideal web sink placed at the end of the web line. Here you can specify either a speed or tension as an input.

Unwind Drum - This component simulates an unwind drum featuring a variable roll radius and inertia used to model the dynamics of a drum as it unwinds the material from the roll.

Wind Drum - - This component simulates an wind drum featuring a variable roll radius and inertia used to model the dynamics of a drum as it winds the material into the roll.

Multiple Webs

Unwind Drum Two Webs - The Unwind Drum Two Webs component simulates the simultaneous unwinding of two webs, each with a variable roll radius and inertia.

Wind Drum Two Webs - The Wind Drum Two Webs component simulates the simultaneous winding of two separate webs, each featuring a variable roll radius and inertia.

Wind Drum Three Webs - The Wind Drum Three Webs component simulates the simultaneous winding of three separate webs, each with its own variable roll radius and inertia, on a single set of drums.

Wind Drum Four Webs - The Wind Drum Three Webs component simulates the simultaneous winding of four separate webs, each with its own variable roll radius and inertia, on a single set of drums.

This section contains the components that allows to model the laminatin process of R2R systems. This section contains the following components required to be used when a system contains multiple merging webs.

Figure 2.5: Laminating

Merged Web Properties - This property block defines the parmetes of the merged web defining the mechanics of the web and its visualization. The user can specify the web property to merge and Maplesim uses law of mixtures to determine the merged web property.

Web Multiplexer - This is purely an model organizational component used between multiple Web Roller in Component and Multi-Web Roller Out component.

Multi-Web Roller In - This component defines the entry configuration of the merging webs into the laminating rollers.

Multi-Web Roller Out - This component captures the merging of multiple webs and the exit configuration for the merged web.

Basic

Span Merge - The Span Merge component captures the merging of multiple webs from a Node Webs Merge component and the exit configuration for the merged web.

Node Merge Two Webs

Node Merge Three Webs

Node Merge Four Webs

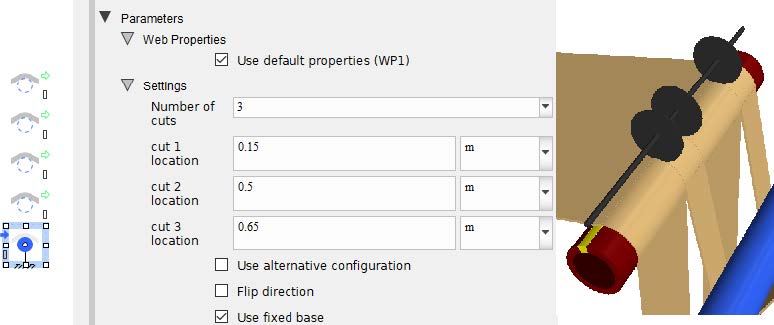

This component can be used to divide the upstream web into two or more webs downstream. Ideally this component must be between the upstream Span and multiple downstream slitted span components forthe model to work.

Figure 2.6: Slitting

The option for the slitting process can be found in the components property section which allows the user to specify the number of slits respectively.

Figure 2.7: Slitting process definition

Sensors play a crucial role in extracting variable data from the simulation, which can be utilized for a variety of purposes such as control feedback, monitoring system performance etc.

Load cell - The Load Cell component measures the force components in the X and Y directions.

Inclinometer - Measure the inclination angle of the line from one frame to another.

Figure 2.8: Sensors

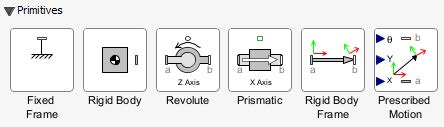

The Primitives section of the library is a specialized subset of the Multibody library, designed specifically for modeling planar mechanisms within roll-to-roll (R2R) systems.

Figure 2.9: components under Primitives

Fixed Frame - A stationary frame used to position the Web handling components corresponding to the XY Plane.

Rigid Body - The Rigid Body component models a rigid body that can move in the x-y plane and rotate about the z axis.

Revolute - The Revolute component allows a rotational motion around an axis in the z-direction.

Prismatic - The Prismatic component allows translational motion along either the x or y axis.

Rigid Body Frame - The Rigid Body Frame component models a fixed displacement in the x-y plane followed by a rotation about the z-axis.

Prescribed Motion - The Prescribed Motion component converts scalar signals to translation in the X-Y plane and rotation around the Z-axis.

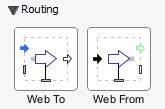

This section is used to simplify rouitng of the web line in a model.

Figure 2.10: Routing Components

Web To - This component defines where the web is coming from and must be connected with the Web From component.

Web From - This component defines where the web is coming from and must be connected with the Web To component.

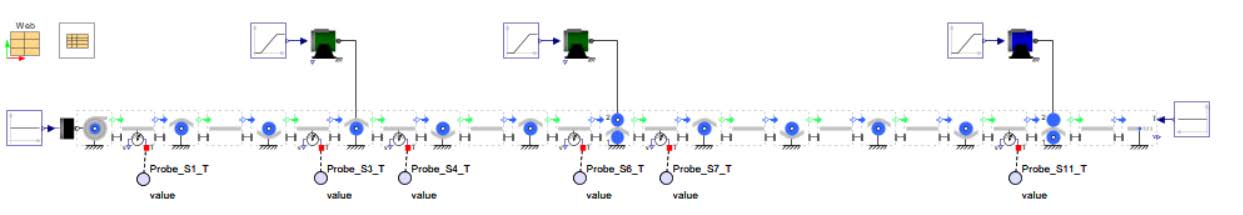

In this chapter, we will begin by learning how to construct a basic web handling model i.e. a simple web line. The objective is to introduce you to the foundational components and modeling techniques involved in simulating roll-to-roll (R2R) systems. Through this hands-on exercise, you will gain an understanding of how to configure the system, define key parameters, and run simulations to observe the web’s mechanical behavior.

Once the simple web line is built, we will explore how to analyze the simulation results, focusing on important variables that have impact on the system. Later we will go through the preocess of expanding the model and testing a basic control loop.

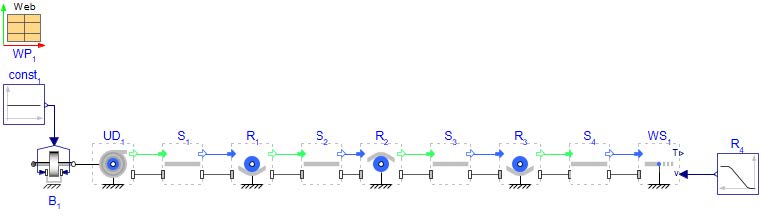

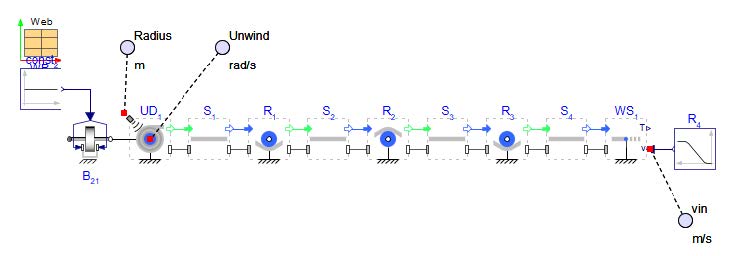

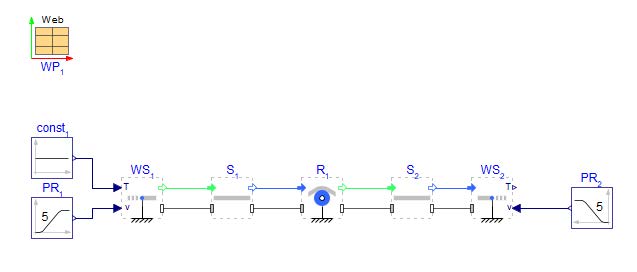

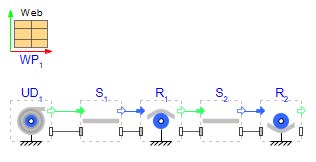

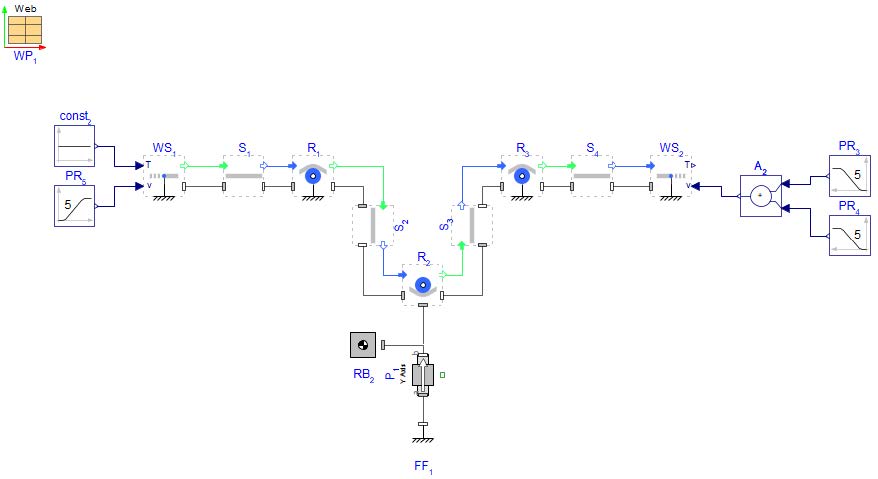

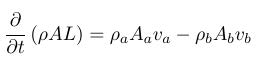

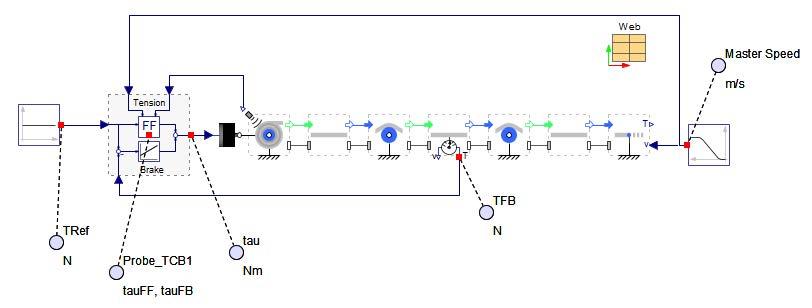

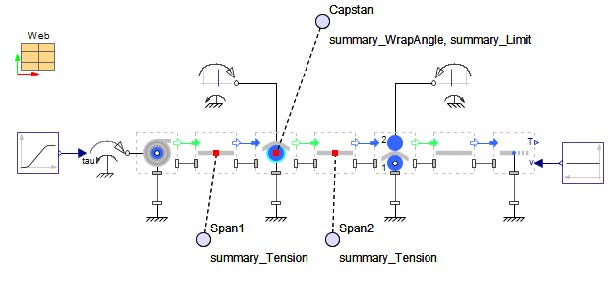

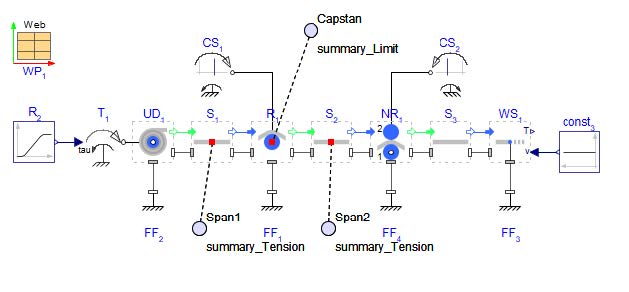

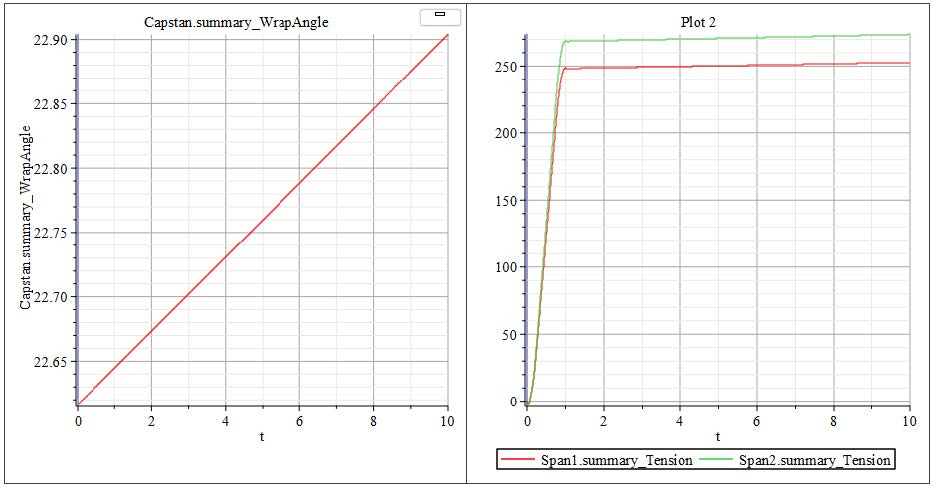

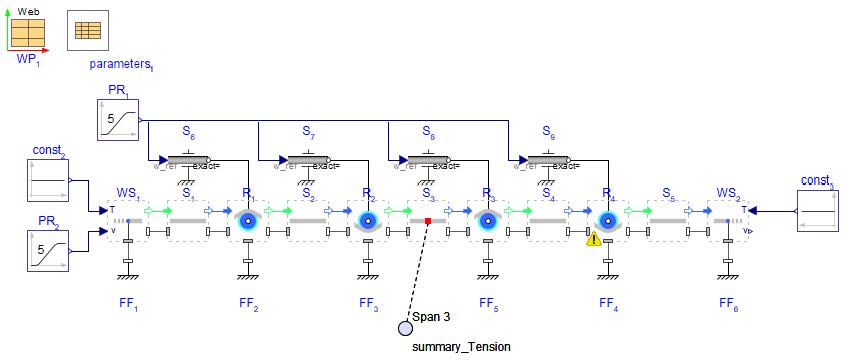

This simple web line will use 1 Unwind Drum, 3 Rollers and 3 Web Spans. The first step is the creation of the model in MapleSim. Figure 2.11 shows the model structure that will be created.

Nonetheless, we suggest following the instructions below to build the model step by step. The figure below provides an overview of the model that will be built in this section:

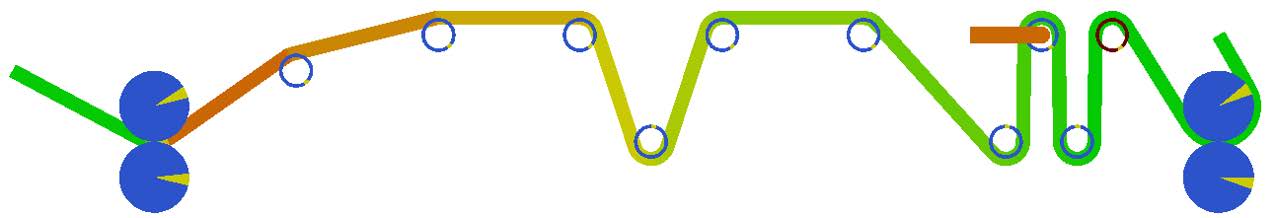

Figure 2.11: Structure of the start model

Open a new MapleSim document and save it as “StartModel.msim”.

Add a WebProperties from the Web Handling palette. The non-default parameters of the WebProperties are: W = 0.3[m], th = 0.005[m] which represent the width and thickness of the material.

Add a Unwind Drum from the Web Handling > Sources and Sinks palette. The non-default parameters of the Unwind Drum are: Dinit = 1[m], L = 0.4[m].

Check the box for Use Fixed Base within the Unwind Drum component. This allows us to define the coordinates for Drum respectively. Enter the values for the fixed base location r=[-1,0][m].

Add 4 Span components from the Web Handling > Webs palette.

Add 3 Roller components from the Web Handling > Rollers and place them between the Span components. Change the parameter L = 0.4[m], and check the box for Use Fixed Base in all Roller components.

Check the parameters of the left Roller (R1) and change the diameter D = 0.1[m]. So that, the left Roller would be smaller then the other rollers. Also in Roller R1 parameters, enter the position for the base r=[-0.3,-0.1][m].

Change the setting of the left and the right Roller (R1 and R3) and activate the "Use alternative configuration". This means the web is now under the Roller (This can be confirmed in the GUI on the canvas).

Open the parameters of Roller (R2). Change the following:

uncheck the parameter Use cylindrical geometry

mass m = 20[kg]

inertia J = 0.1[kgm].

postion for fixed base r=[0,0.5][m].

Add the fixed base position location of Roller (R3) to be r=[0.7,0][m].

Add a Web Sink from the Web Handling > Sources and Sinks palette. Check the box in the component parameters for Use Fixed Base and enter the position value r=[1,-0.1][m].

Add a Ramp block from the Signal Blocks > Common as shown in Figure 2.11. This defines the speed ramp for the startup phase of the machine. The parameters of the Ramp are:

height = 5[−]

Tr = 10[s]

Activate Smooth corners

smoothness = 0.5[−]

offset = 0[−]

T0 = 0[s]

Add a Brake2 block from the 1-D Mechanical > Rotational > Clutches and Brakes as shown in Figure 2.11. The non-default parameters of the Brake2 are: µc = 0.5[−] and reff = 0.2[m].

Add a Constant block from the Signal Blocks > Common as shown in Figure 2.11. This defines the braking force of the Brake2 . The parameter is k = 750[−].

Connect the components as shown in Figure 2.11.

Click ‘Run Simulation’ (![]() )!

)!

Once the simulation starts, The Analysis window will automatically open with the results displayed after the completion of the simulation.

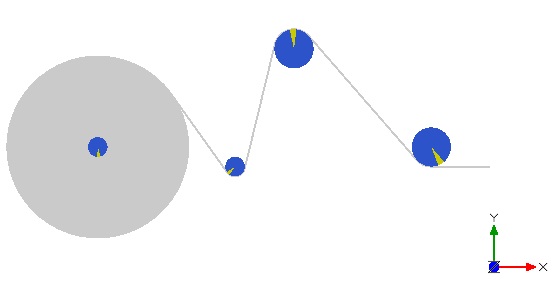

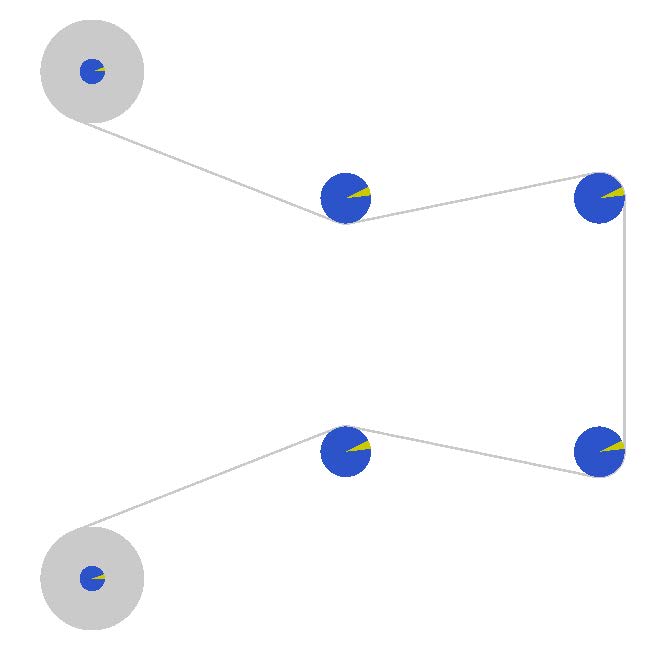

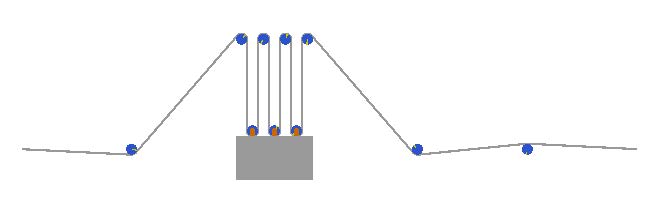

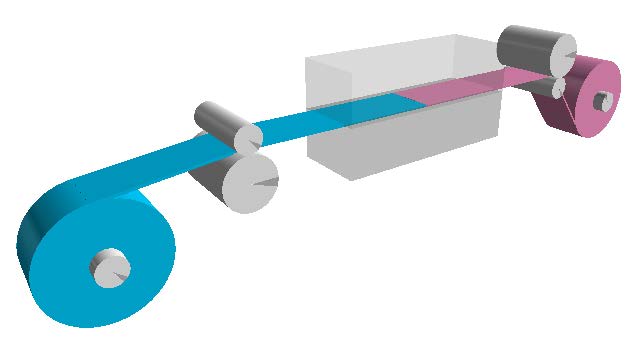

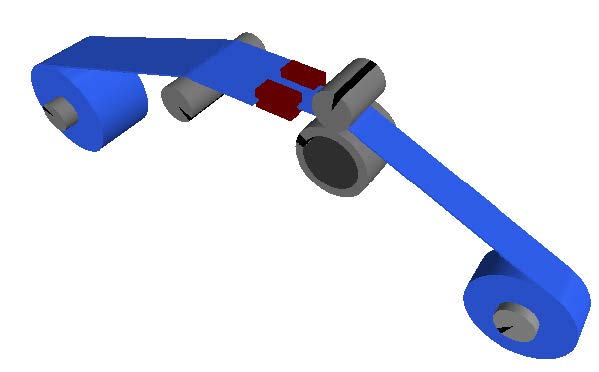

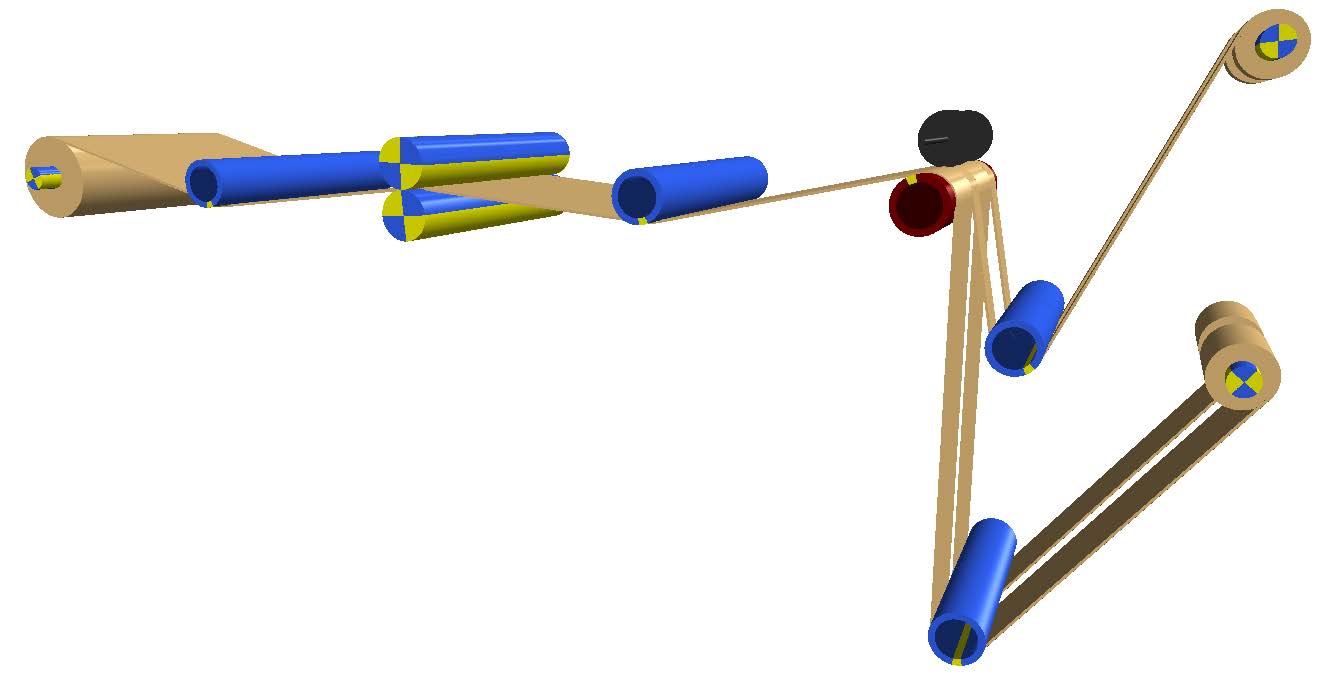

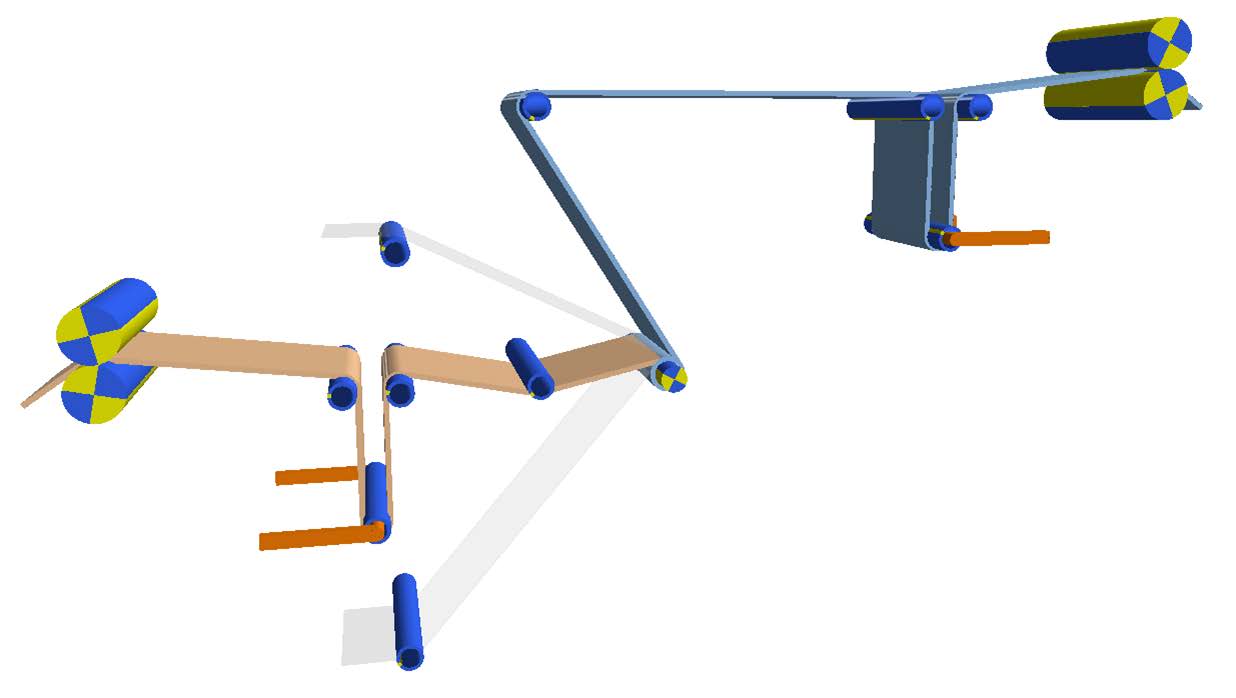

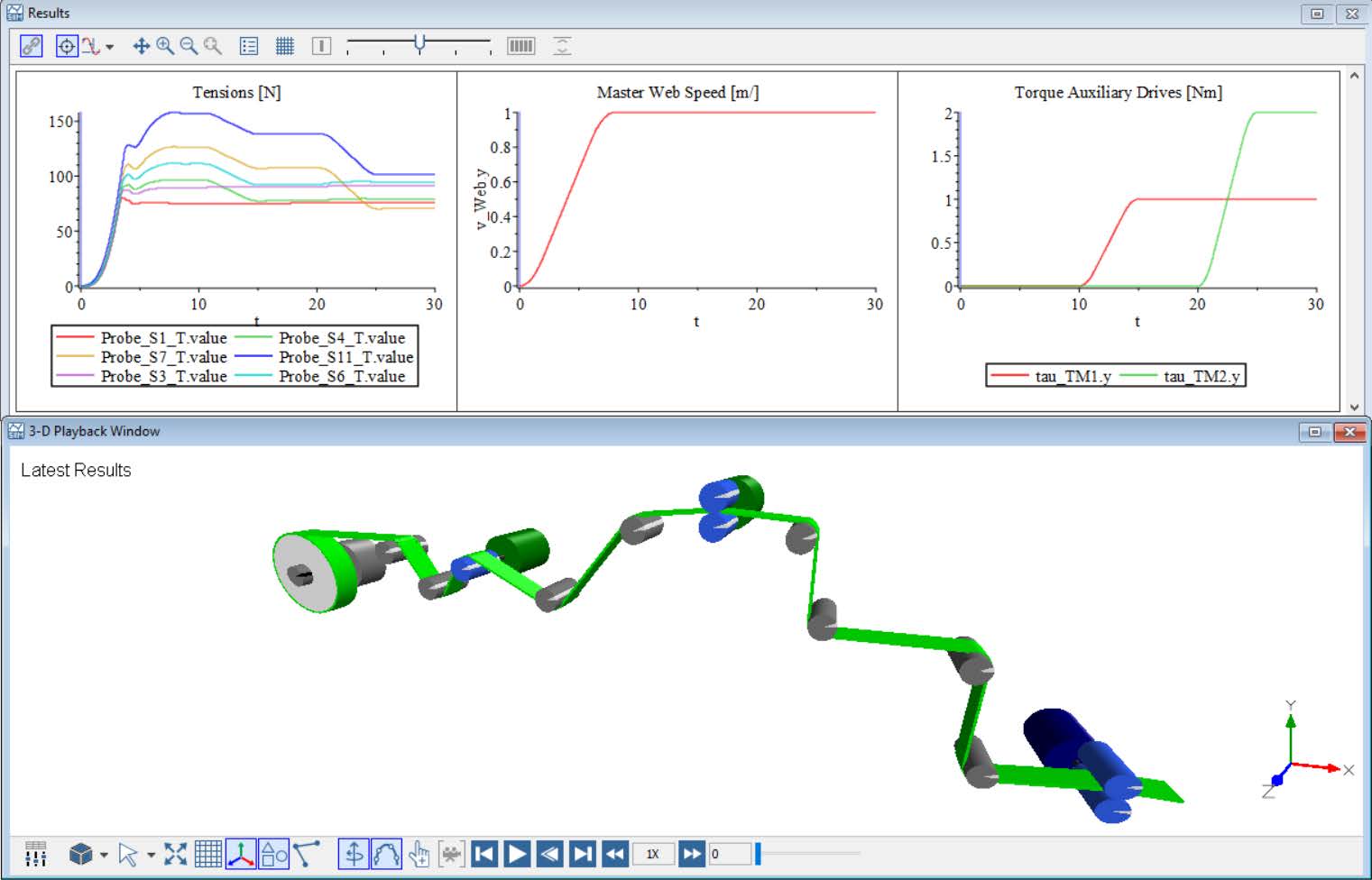

At first you can see the 3D view in the 3-D Playback Window (Figure 2.12). It shows the structure of the web handling model based on the defined coordinates of the Fixed Base positions in each component and the prescribed geometry of the rollers.

Figure 2.12: 3D view of the machine

Click on the ‘Select view type’ and change the view to ‘Front Orthographic View’. Note that the model approach is planar only and as such, the z-axis is not taken into account.

On hitting the play window we can now see the animation of the system simulated for 10 seconds time.

Figure 2.13: 2D depiction of the machine

Now lets gain a better understanding of the results of this model by plotting the system variables and analyzing the results. To do that lets add some probes in the canvas as shown below.

Figure 2.14: Added Probes to the Model use in Figure 2.11

The first probe is added within Unwind Drum component. The radius of the unwinder has to be selected to enable the port by checking the Enable Radius sensor in the component parameter section.

The second probe from the left measures the angular velocity of the Unwind Drum .

The last probe(From the left) measures the velocity output from the Web Sink

Once added, Click ‘Run Simulation’ (![]() )! again and view the plots in the new results window.

)! again and view the plots in the new results window.

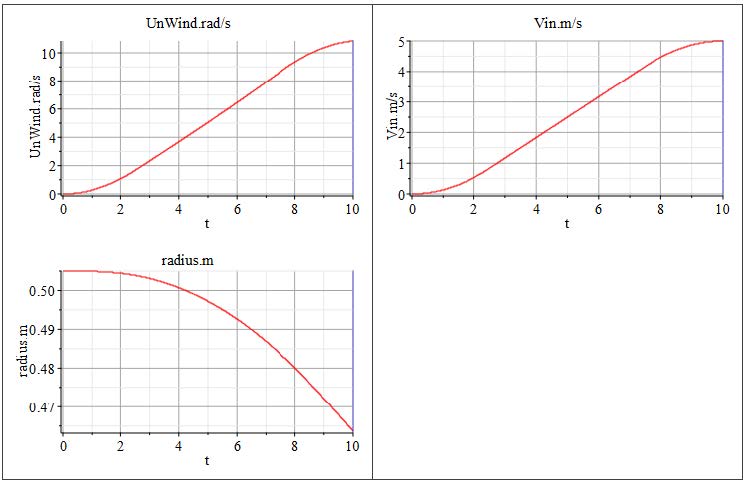

Figure 2.15: Probe plots from Start Model

These results indicate that as the radius of the Unwind Drum decreases, its angular velocity increases in proportion to the velocity specified at the Web Sink . This behavior reflects the principle of conservation of linear velocity which follows that;

v = Rω (1)

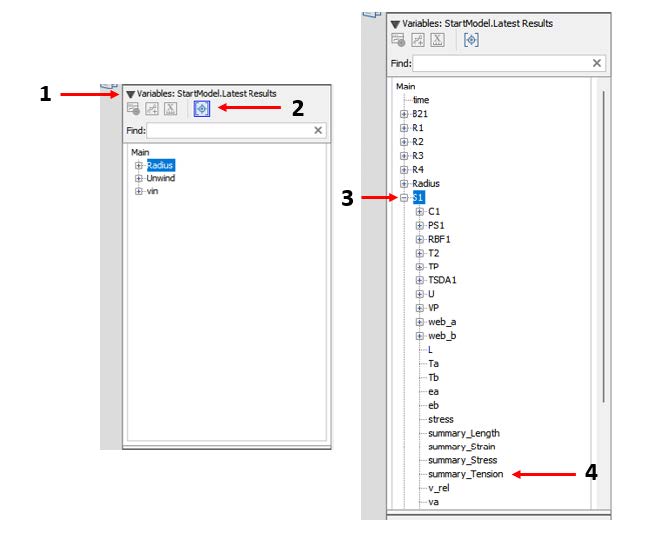

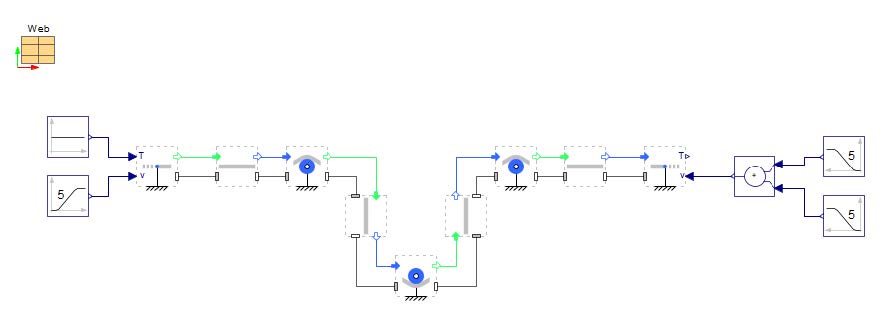

To look at the results of the Span tensions, there are multiple methods. One method is to use a probe on the component, or use the sensor that is located within the Span component. Another method is to create the tension plots in the results window. On the left-hand side palette in the results window, navigate to the section called Variables:StartModel.Latest Results, shown in Figure 2.16. Click the small icon on the far right that shows a probe symbol in square brackets - this will list all the components in the model. Presently, it only shows probed variables.

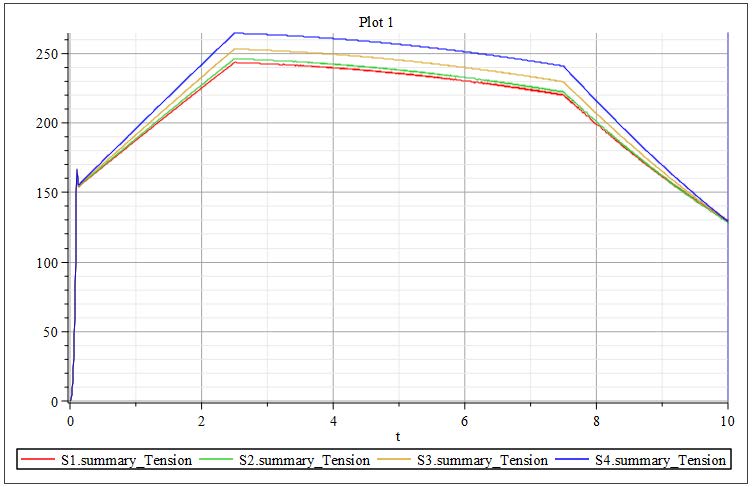

Figure 2.16: Steps to create plots from the results window

In this window there are a list of all the components in the model listed by component name. Click the plus sign (+) next to the component "S1" for Span 1 . Scrolling down there is a parameter called Summary Tension. Alternatively, if you know the name of the variable you are looking for, you can type the name of the variable in the text field Find: at the top of the window. Double click on this parameter and a new plot will open up. This plot shows the tension in Span 1 . Locate this parameter for the other 3 Span components and drag and drop them into the same plot such that they all appear on top of one another (Figure 2.17). Being able to put the parameters on the same graph allows for concise viewing and comparison.

Figure 2.17: Tensions of each span in Start Model

Summary Variables are specialized output variables provided within the Web Handling Library to give users convenient access to key internal parameters in user-defined units. These variables are globally accessible throughout the library and are designed to expose important quantities such as tension, web length, wrap angle, stress, strain, web velocity, and roller angular velocity. Users can customize the units of these summary variables through the Web Property Parameter Block, allowing for consistent output formatting across the model.

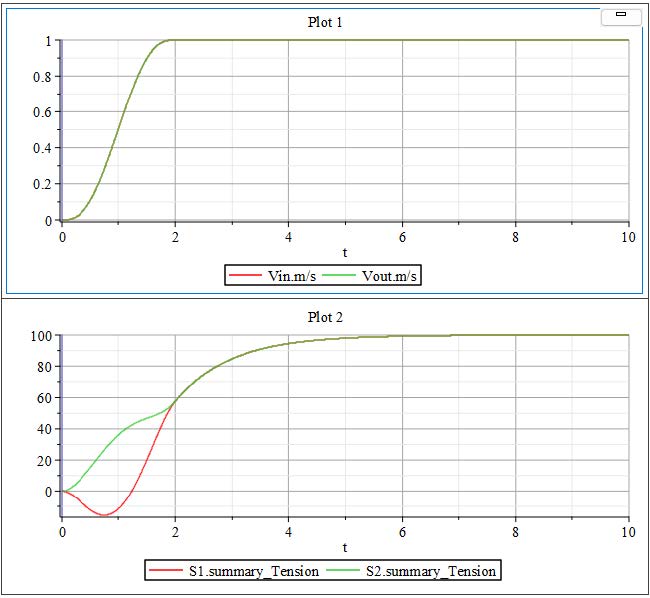

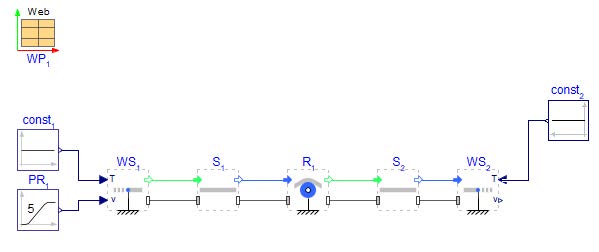

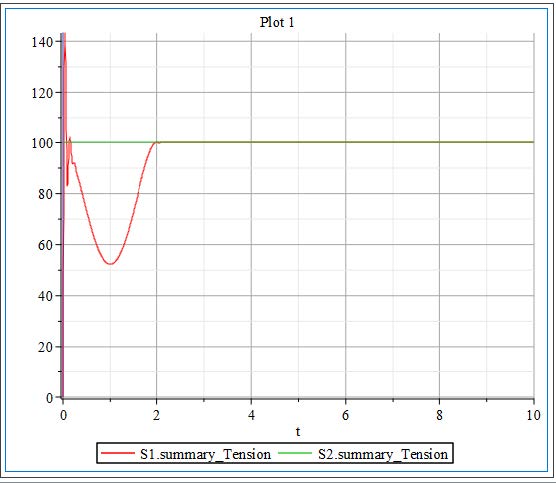

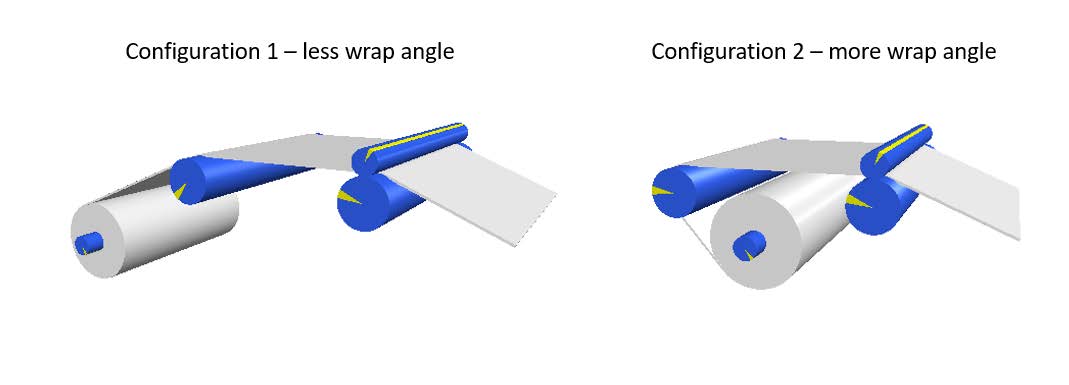

This section will allow a user to understand modeling boundary conditions in a web line and how they impact the results. for this we are goinng to consider a very simple system with just one Roller, a Web Source, and a Web Sink , as well as Spans between the components (Figure 2.18). There is a constant tension input to the web line of 100[N], and a constant velocity of 1[m/s]. By manipulating the inputs of tension and velocity, it will highlight how the two are affected within web lines.

The figure below provides an overview of the model that will be built in this section:

Figure 2.18: Simple model with one roller

Figure 2.19: 3D planar view of system

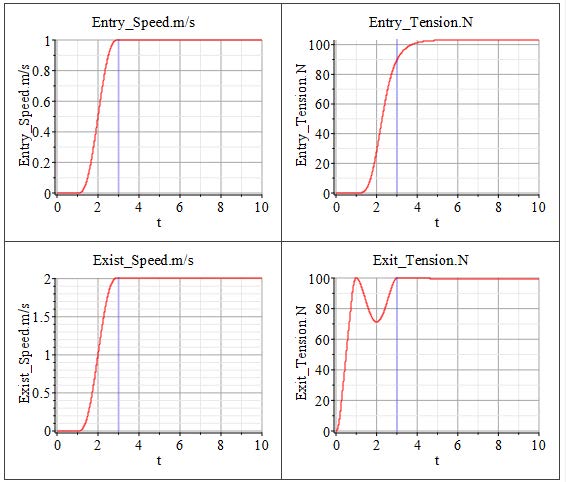

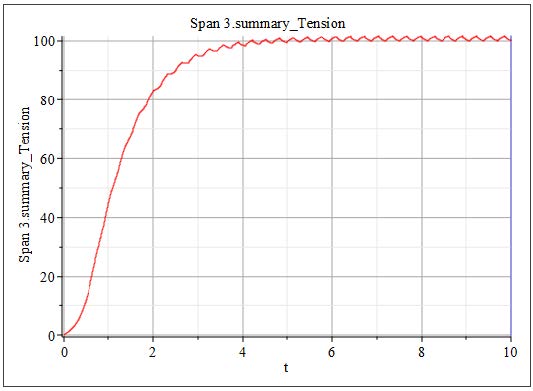

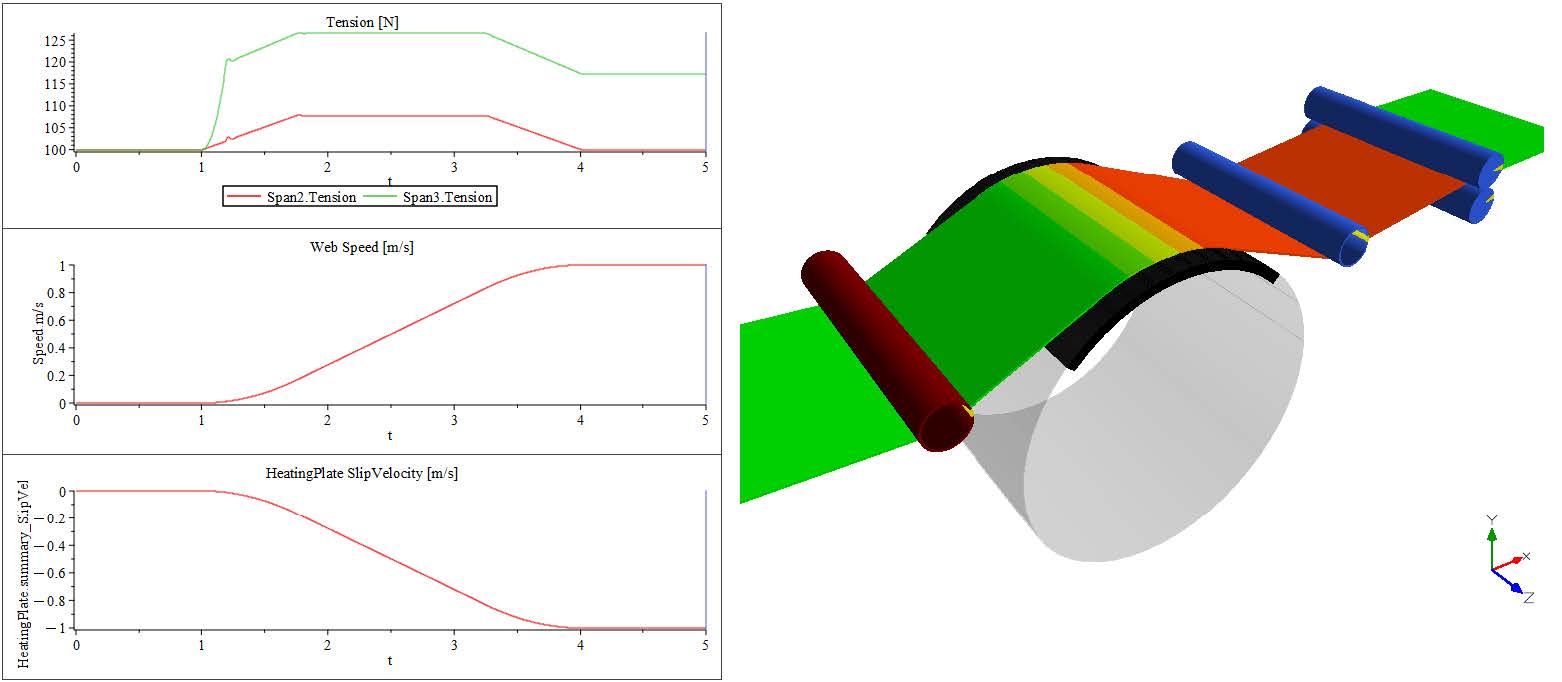

In MapleSim, a Ramp or Poly Ramp component is often used to define velocity profiles in web handling models. This approach helps prevent sudden tension spikes and ensures a smooth initialization of both speed and tension in the system. In the current example, the velocity is set to 1[m/s] at both ends of the web line, creating a consistent tension zone between the web source and sink. This is achieved by explicitly defining the downstream velocity. The results of this simulation are illustrated in Figure 2.20.

Figure 2.20: Results of simple model example

During the initial 2[s] ramp-up period, as the system velocity gradually increases, the web tension experiences noticeable fluctuations. These variations are primarily caused by the inertial effects associated with the acceleration of the Roller components. As the rollers begin to spin up from rest, their inertia resists the change in motion, resulting in dynamic tension changes within the web span.

However, once the rollers have fully accelerated and the system reaches the specified target velocity, the influence of inertia diminishes, and the system stabilizes. At this point, the tension within the web settles at a steady value of 100[N], which corresponds to the defined input tension setpoint. This steady-state condition indicates that the system has successfully transitioned through the ramp phase and achieved balanced web transport under the desired operating conditions.

There is a section of time in which the tension in Span 1 is negative, this means the web is experiencing compression. This is not possible as a web can only be in tension. How can this negative tension be addressed and ultimately reduced?

Explore - Try using larger or smaller values of velocity and tension input and see how it impacts the web line tensions and roller parameters.

The figure below provides an overview of the model that will be built in this section:

Figure 2.21: Simple model example with tension input to web sink

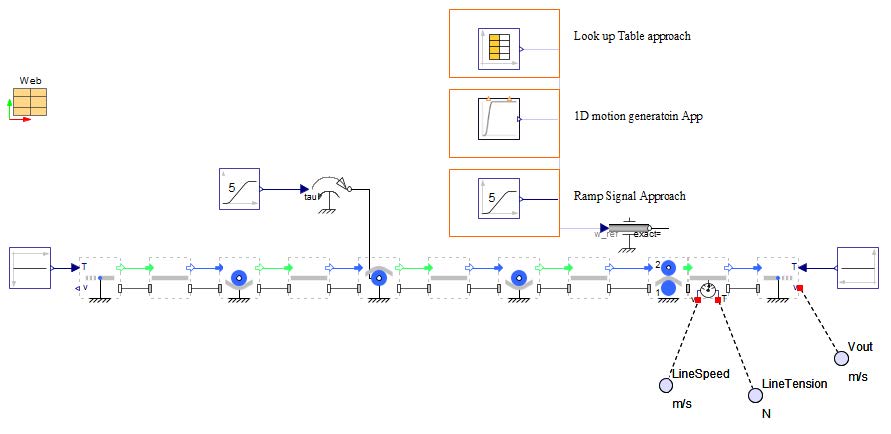

In this section we are going to walk through multiple methods of applying speed and tension control to a web line. The following methods will be explored in this chapter:

Applying actuation to a pull roller

Applying system data through usage of an interpolation table

Applying generated speed profile(s) in MapleSim 1D Motion Generation App

In the next section we will go a step further and apply tension zones to a web line using these methods. Figure 2.23 will be used as reference to the methods discussed.

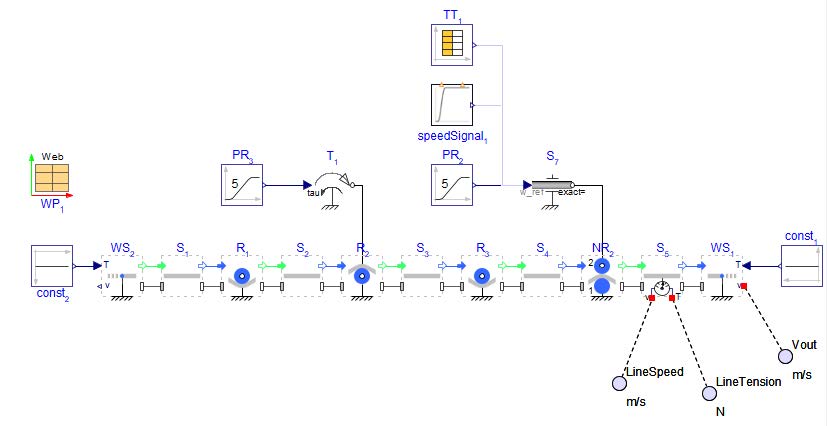

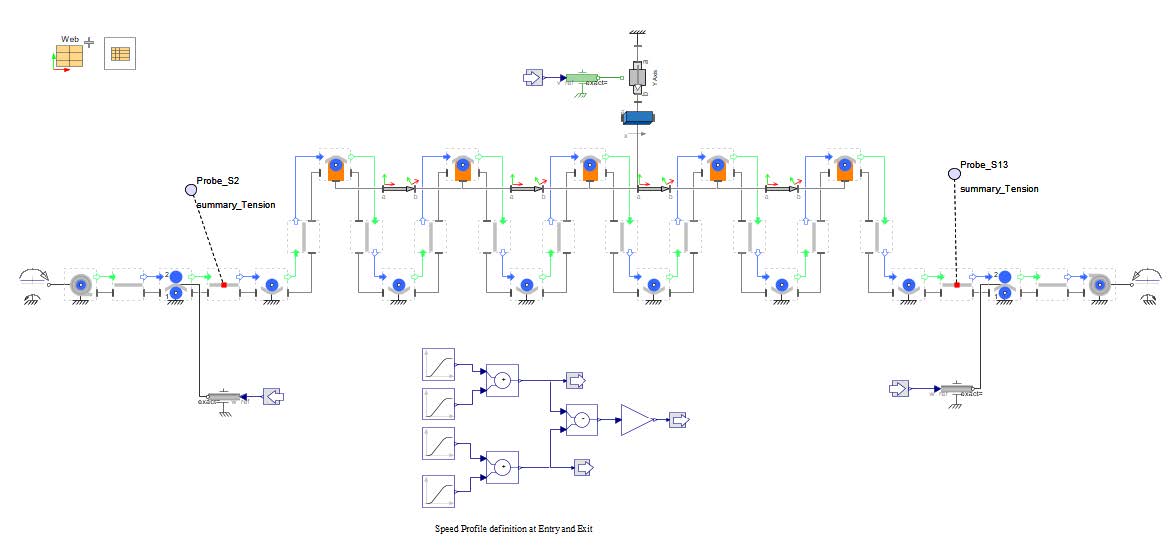

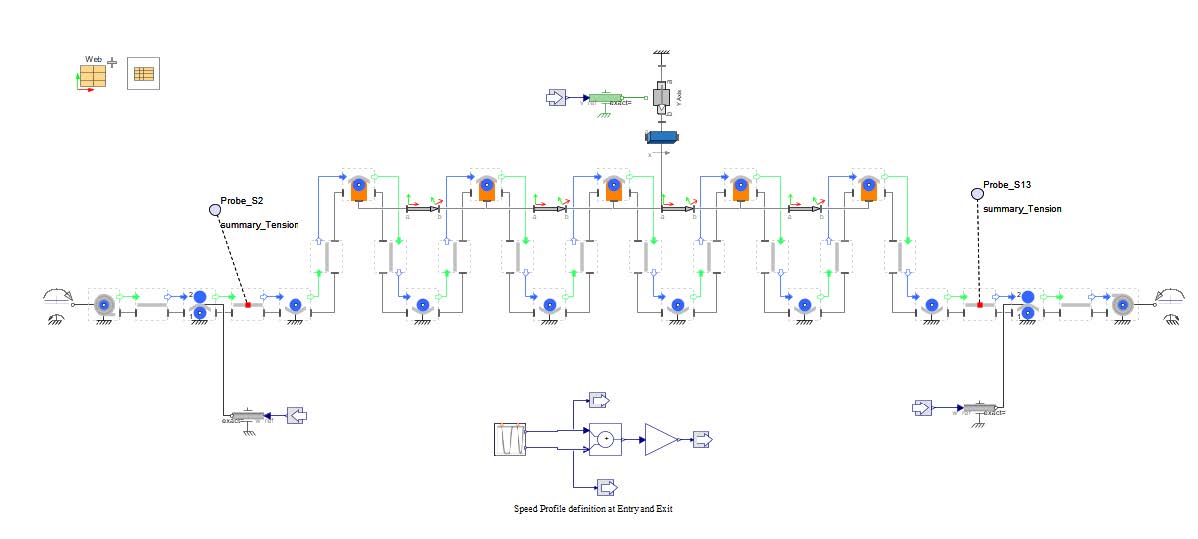

The figure below provides an overview of the model:

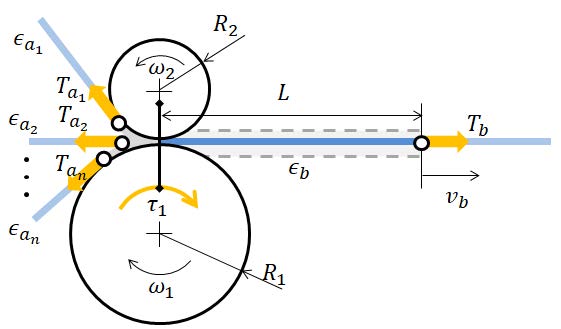

Figure 2.23: Schematic of a web line with a pull roller and actuated nip roller

Actuated Nip Roller: In the configuration illustrated in Figure 2.23, the Nip Roller is actively driven by a 1D mechanical Rotational Speed driver, which directly controls the rotational speed of the roller. This component is responsible for applying a defined speed profile to the nip roller, making it the primary drive element within the web handling system.Complementing the primary drive, a torque controller is linked to a Pull Roller , which acts as an auxiliary drive. This auxiliary roller does not dictate the web speed but contributes additional torque to assist the system.

More detailed information regarding the various Nip Rollers can be studied in the upcoming sections of the training

Pull Roller: A pull Roller is also known as a driven Roller . This is a Roller that is actuated by a motor. There are multiple methods to implement this in MapleSim, the two straightforward methods are using a Rotational Speed driver in the 1-D Mechanical > Rotational library, or by adding a Torque driver to the Roller shown in Figure 2.23. Both of these components would connect to the 1-D rotational

flange that is located at the center of each Roller component. This actuated Roller is the auxiliary drive to the Nip Roller in this system and subsequently creates a second tension zone in the system.

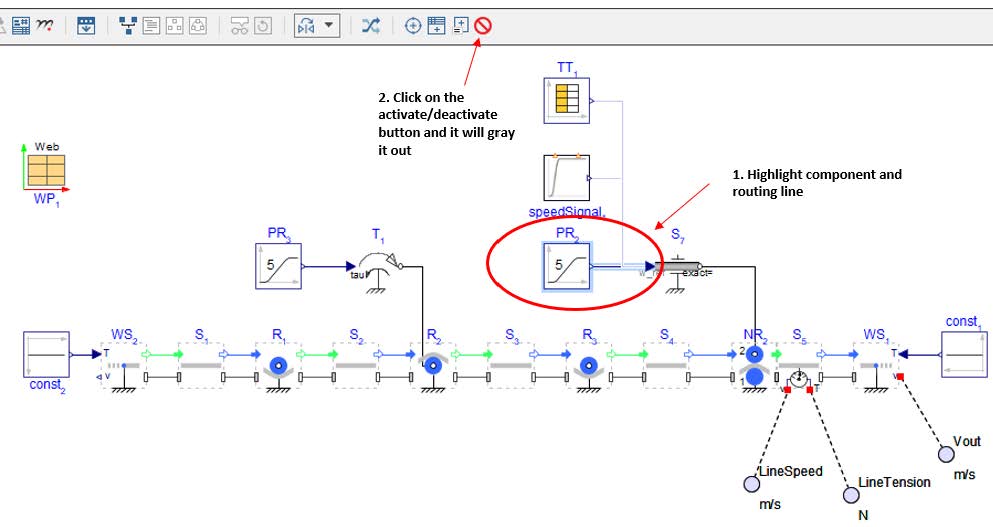

Using data through interpolation tables: When data is accessible, MapleSim interpolation Time Table component is a straightforward method to apply velocity and/or tension profiles to a web line. The data can be attached to the model in the form of an excel file (.xlsx) or .csv file and referenced by the component. It is vital that the first column of data is time in [seconds] and that the simulation time set in MapleSim match the time in the table in order to obtain accurate results. Using the model in Figure 2.23, deactivate (shown in Figure 2.24) the Poly Ramp and activate the Time Table for the input to the Speed Driver .

Figure 2.24: How to activate/deactivate components in MapleSim

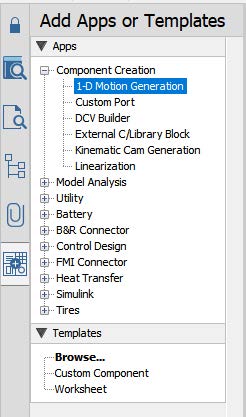

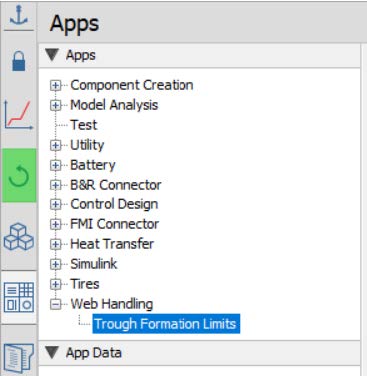

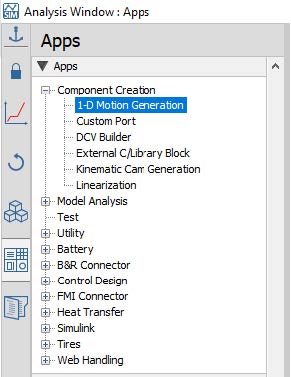

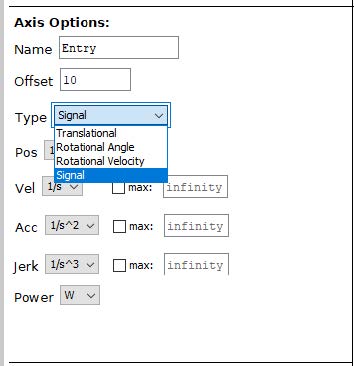

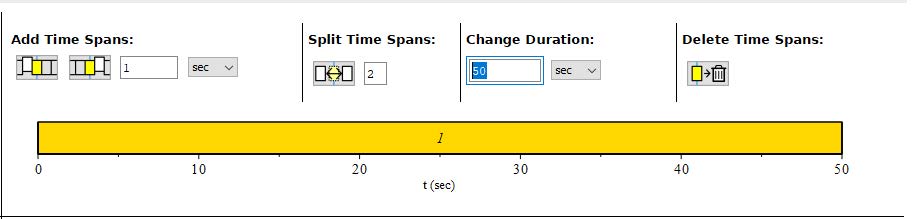

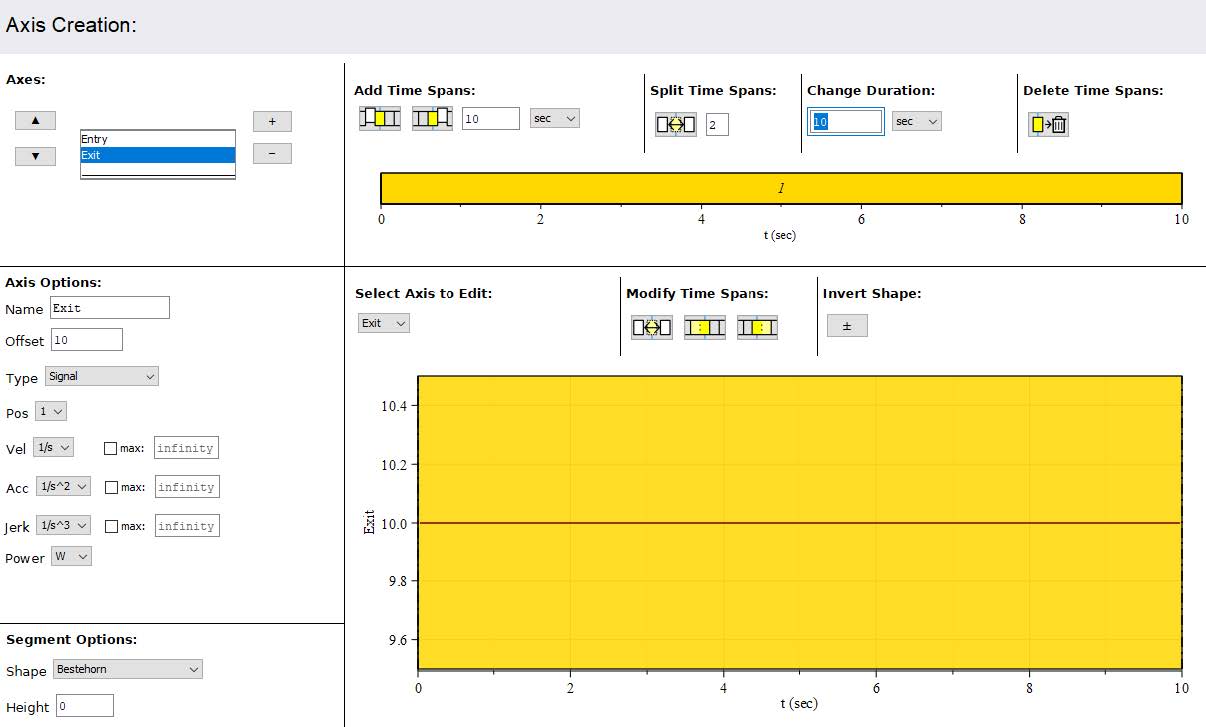

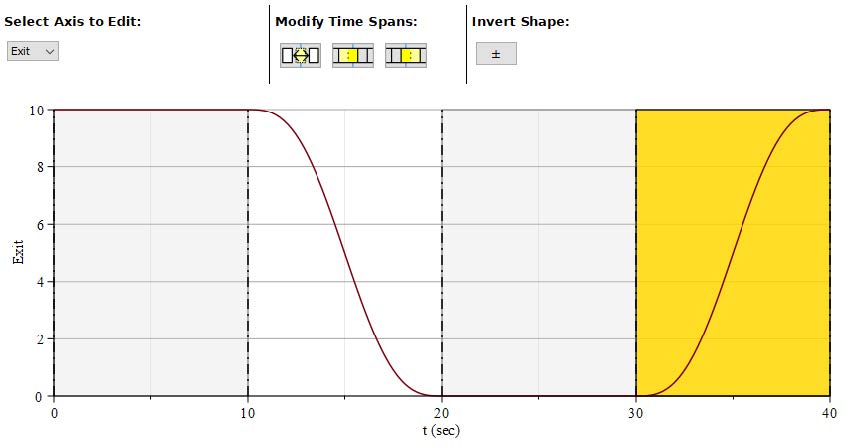

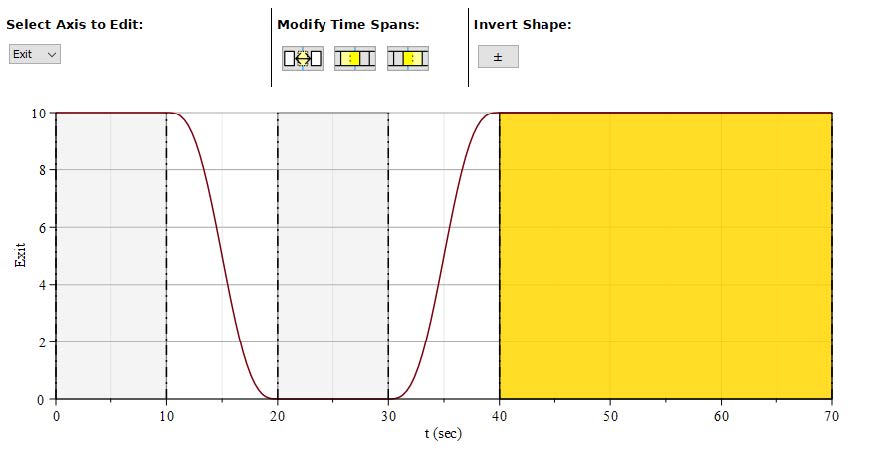

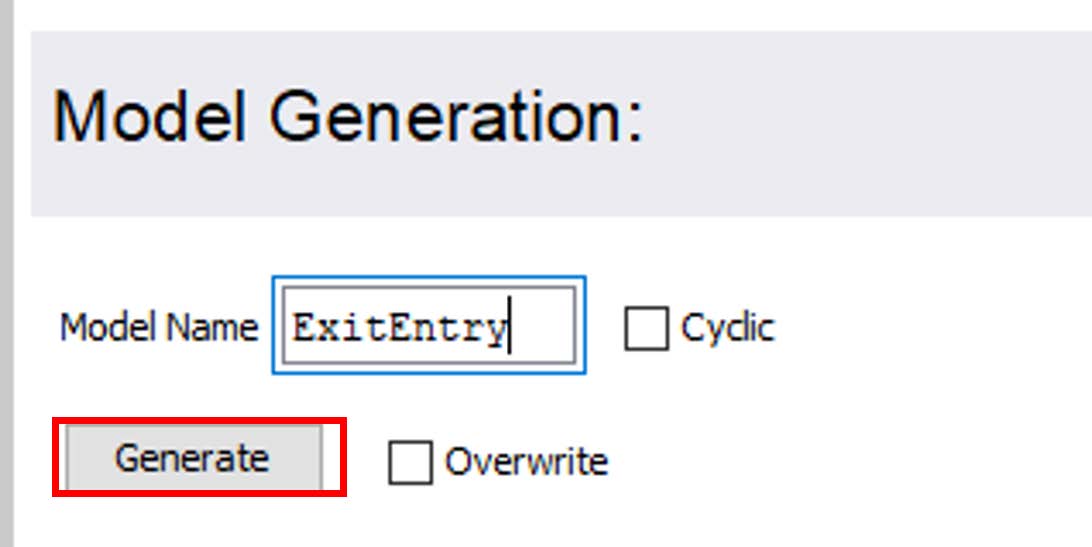

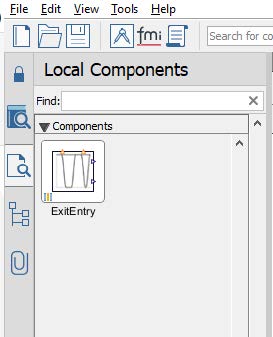

1D Motion Generation app: The 1-D motion generation app can also be utilized to create unique curves as a signal input for the velocities of the web line. This app can be found under the Add Apps or Templates > Component Generation (Figure 2.25). Creating motion profiles in this app are explored in a separate training chapter dedicated fully to the app.

Figure 2.25: Location of 1D motion app

More detailed information on how to use the 1D motion generation App will be explained in the upcoming chapters.

Now that we’ve explored how to introduce tension and speed control into a web handling system, we can move forward by implementing tension zones within a more complex, larger-scale model. A tension zone refers to any segment of web located between two independently driven axes, such as pull rollers, actuated nip rollers, or other types of controlled rotational components.

In the previous example, we added an auxiliary drive, which effectively divided the web line into two separate tension zones. Each zone operates independently in terms of its tension profile, governed by the relative speeds of the drives at either end of the zone. If additional tension zones are required, you can simply introduce more driven or pull rollers, each configured with its own speed input. By adjusting the speed of each roller appropriately, you define the tension gradient across the web spans between them.

The tension in a Web Span arises from the difference in linear velocity between the upstream and downstream components—whether they are rollers, drums, or web sources/sinks. When one driven component rotates at a slightly higher speed than another, it stretches the web between them, creating positive tension. Conversely, if the downstream component is slower, it can reduce the tension or even introduce slack, depending on the web’s mechanical properties and material behavior.

The figure below provides an overview of the model that will be built in this section:

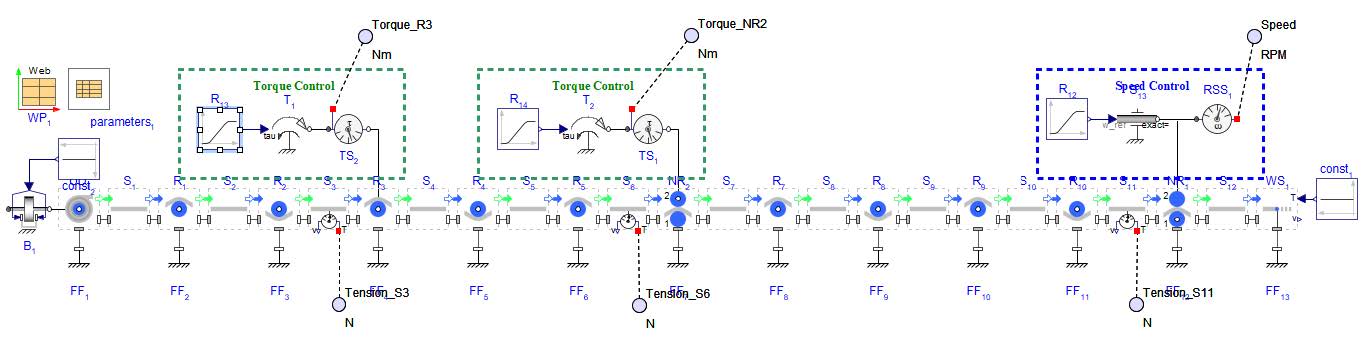

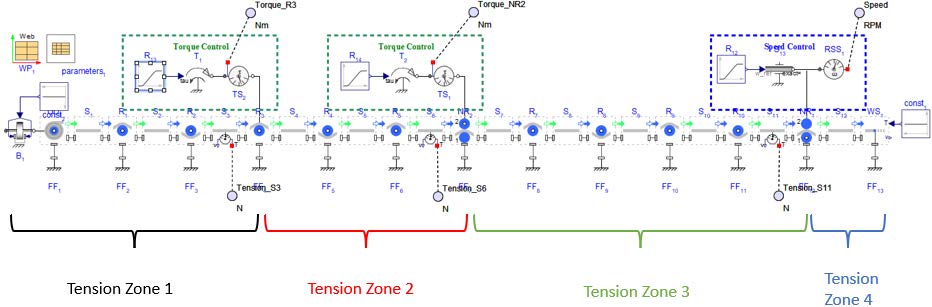

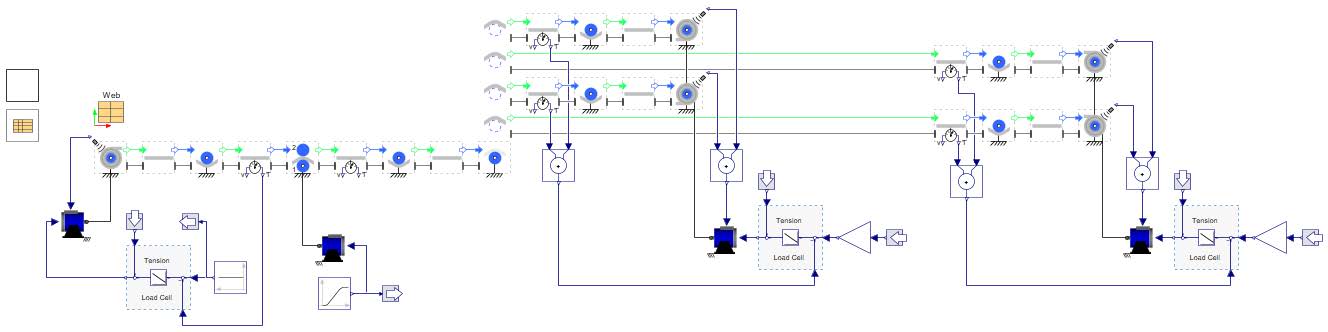

Figure 2.26: A Multi drive web line system to explore tension zones

The main drive for this example model is connected to the Nip Roller on the far right labeled NR1 . This is speed controlled and as such controls the speed of the web. It has a input of 20[rad/s] and 10[s] of ramp up.

There are two additional auxiliary drives to the system, each of which are torque controlled and thus reduce the web tension downstream. Each section of web line between the actuated rollers is a tension zone. It can be broken down into the tension zones as seen in Figure 2.27.

Zone 1 - Starts with the Unwind Drum to the first driven Roller, R3

Zone 2 - From R3 to the second actuated Roller which is a Nip Roller, NR2

Zone 3 - From NR2 to the last Nip Roller, NR1

Zone 4 - NR1 to the Web Sink (since this example ends with a truncated line, the end of the zone would be at the next location of actuation or the Wind Drum for the system).

Figure 2.27: Tension zones highlighted for multi drive example

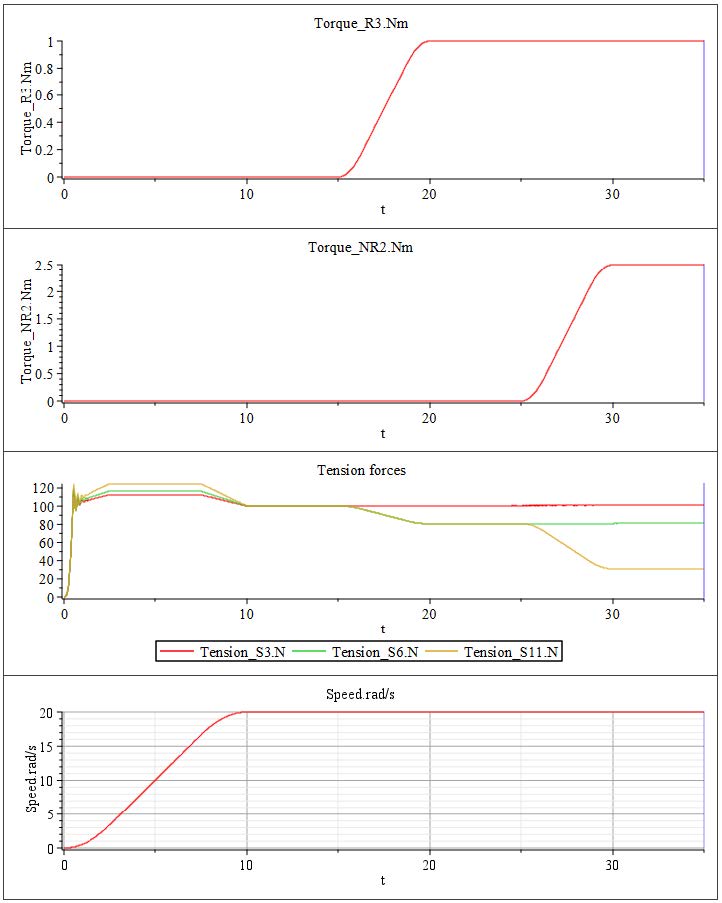

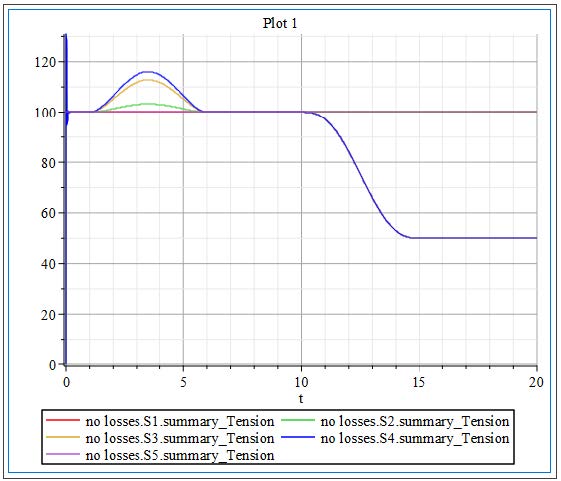

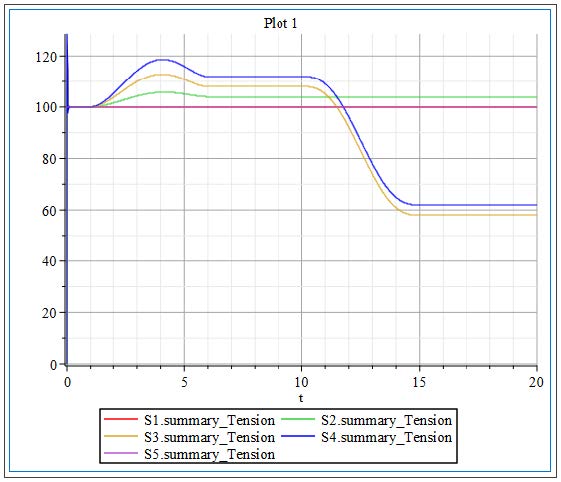

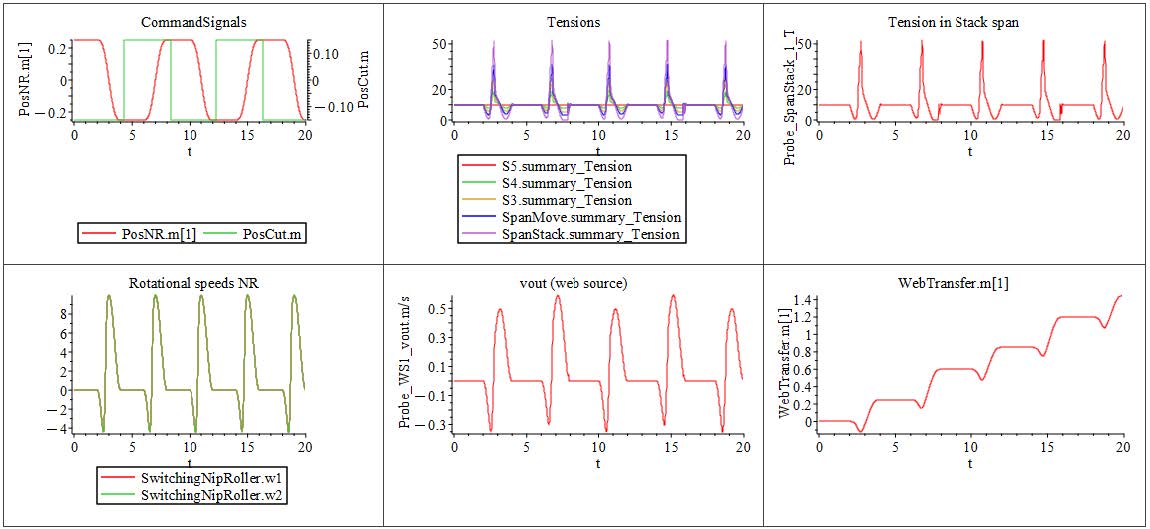

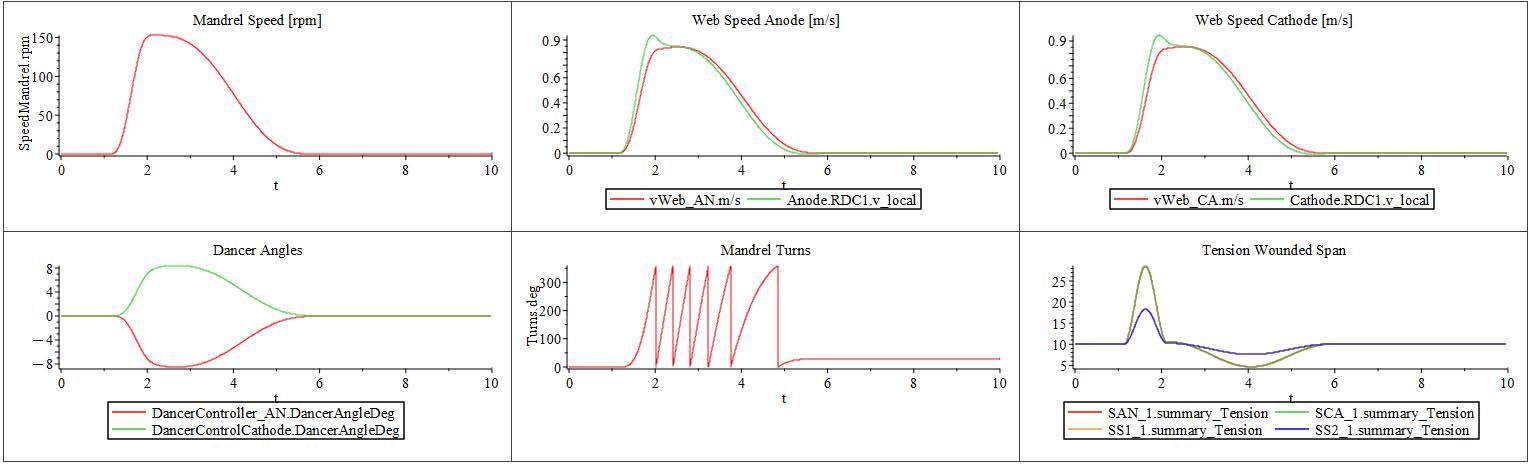

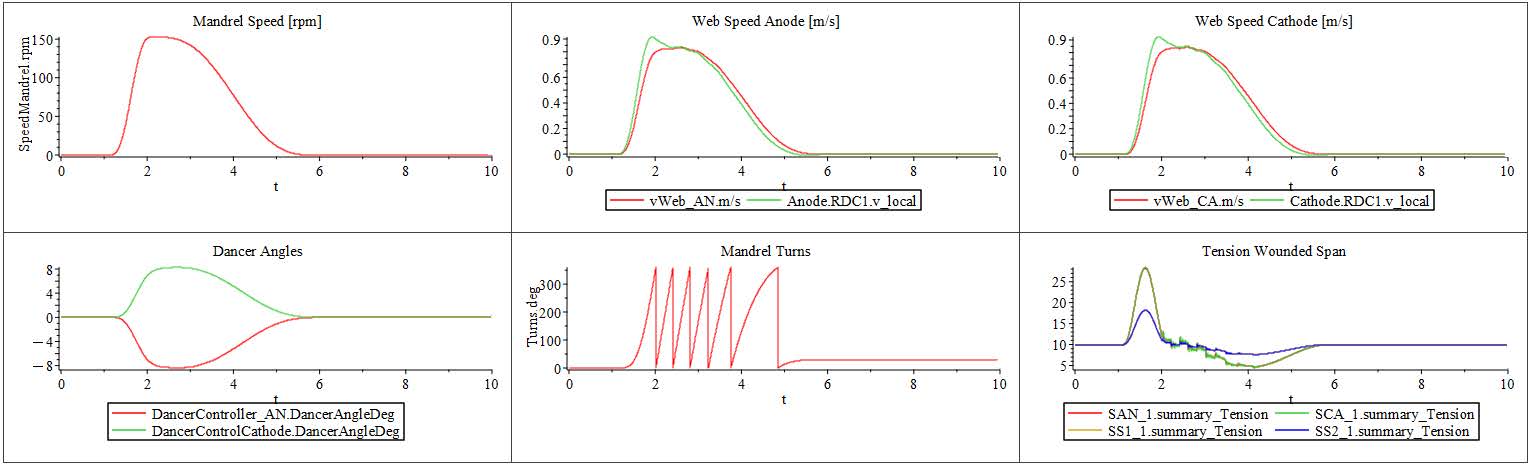

Looking at the plotted results seen in Figure 2.28, there is a noticeable affect of each driven Roller on the web tension. The resulting simulated torques and speed of each driven Roller are stacked on top of each other along with the tensions of some Spans , allowing for ease of analysis.

Figure 2.28: Results of multi tension zone system

0 - 10 [s]: The primary drive for the line (Nip Roller 1 with Speed Driver ) is started. The velocity is increasing over the span of 10[s], reaching the target speed of 20[rad/s]. During this span of time, the web line is initializing and accelerating. There are small spikes in the tensions as the web overcomes the Roller inertias during the acceleration.

T = τ/R (2)

20 - 35 [s]: At 25[s] the second auxiliary driver Nip Roller 2 is actuated applying an additional torque to the line of 2.5[Nm]. This further reduces tensions in the line and highlights the three tension zones that have been created. The line from the Unwind Drum to R3 remains constant at 100[N], then the tension decreases by 20[N] between R3 and NR2 . The last tension zone of the line has an additional decrease of 50[N] in addition to the previous decrease of 20[N] at t=20[s].

This results in a total decrease of 70[N] down to a value of 30[N] affecting the line from NR2 to the NR1 .

This example highlights the ability to control various tension zones in one web line by utilizing a few actuated Rollers and Nip Rollers . This allows for various decreases in web tension downstream.

This section explores two methods that employ an alternate way of constructing a web line. One method is by building a section of web line that goes from right to left and another is by utilizing Maple to input configuration settings for web lines.

The figure below provides an overview of the model that will be built in this section:

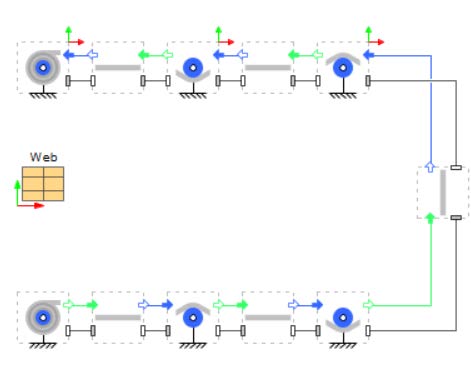

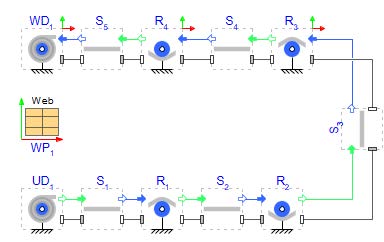

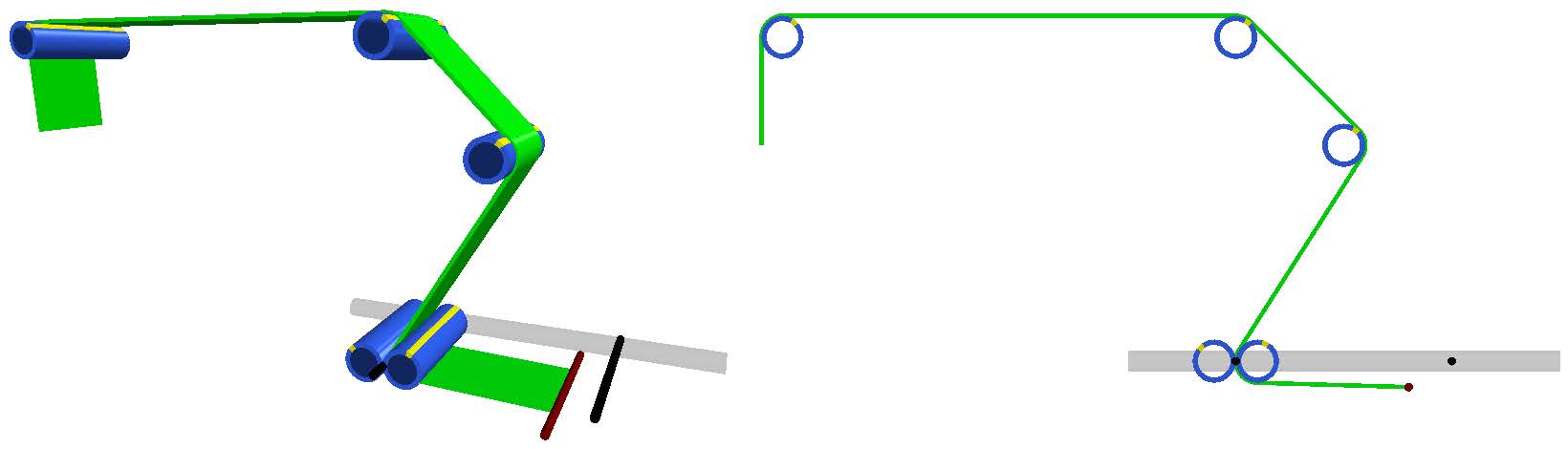

Figure 2.29: Web line Reverse Model Layout

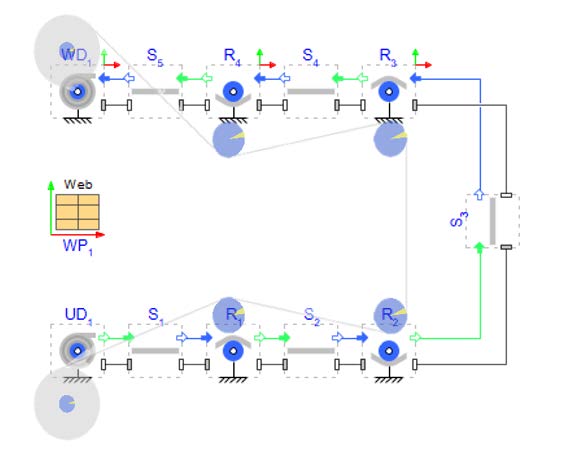

Up until now each web line has been modeled moving in the direction of left to right but not all web lines are constructed in just one direction. This section will discuss how to create web lines that move from right to left and incorporate portions that also move from left to right. The model that will be built will reflect Figure 2.30. There will be an Unwind Drum that feeds into a configuration of rollers moving from left to right then the line will make a 90 degree turn and change direction to be moving from right to left into a Wind Drum.

Figure 2.30: 3D view of the web handling machine

Open a new MapleSim document and save it as “WebLineReverse.msim”. Start with the lower path first, this is similar to creating the model in the first section. Place and connect the required components like the model structure specified in Figure 2.31.

Figure 2.31: First part of the model structure

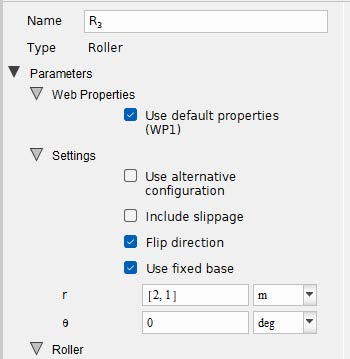

Now starts the section of web that runs in the opposite direction (right to left). A good way to model it is using the Flip Direction box within the Roller component as seen in Figure 2.32. This will place a coordinate frame at the top left corner of the Roller icon as an indication that it is flipped. This indicates that the web is now traveling from right to left (Figure 2.33).

Figure 2.32: Location of Flip Direction Box in component

![]()

Figure 2.33: Roller Icon with flip direction box checked

Because of the flip direction box, the components do not have to be rotated. However, to match the direction of the line with what is on the canvas, the components can be flipped horizontally (right click and flip horizontal or CTRL + H). Doing one flip horizontal in combination with the Flip Direction box will change the web line direction from left to right to be from right to left.

Add the Span S3 and connect it with Roller R2. Optional: Rotate the span once counterclockwise.

Add the Roller R3, check the box for Flip Direction, also check the box for Use Fixed base. Connect it with Span S3. Flip the component once horizontally.

Repeat the last step with Span S4, Roller R4, Span S5, Wind Drum WD1.

Define the positions in each Roller Fixed base according to the following table:

Roller |

UD1 |

R1 |

R2 |

R3 |

R4 |

WD1 |

x [m] |

0.0 |

1.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

1.0 |

0.0 |

y [m] |

-0.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.5 |

Connect all components and change whether the span is on top of or under the Roller by toggling on or off the Use alternative configuration parameter for the corresponding Rollers as can be seen in Figure 2.34.

Figure 2.34 shows the model structure of the entire model.

Figure 2.34: Entire model structure

Click ‘Run Simulation’ ( ![]() ) and check the 3D view! There are no probes in the model because the focus is to create the model structure. By having this option to change the direction of the web path, it provides a more intuitive and more accurate visual representation of the web line. Figure 2.35 shows how the model orientation on the MapleSim canvas now matches the 3D visualization.

) and check the 3D view! There are no probes in the model because the focus is to create the model structure. By having this option to change the direction of the web path, it provides a more intuitive and more accurate visual representation of the web line. Figure 2.35 shows how the model orientation on the MapleSim canvas now matches the 3D visualization.

Figure 2.35: Comparing model structure and 3D view

Another example of a reverse, or right to left web path model can be found in the MapleSim example palette under Help > Examples > Web Handling Examples > Right-to-Left Web Line . See Figure 2.36.

Figure 2.36: MapleSim model of a right to left orientated web line

The following sub section captures the main parts of most Web Handling simulation projects in MapleSim. The required information is broken down to three (color-coded) levels. Every next level needs the information of the level before.

Level 1 model: This is the initial model capturing the web line basics. It is useful to study the modeling capabilities and to establish a plan for adding the required detail/fidelity for validation and focused parameter/design studies in the subsequent phases.

All axes: Pull Rollers, Idle Rollers, Nips, and Wind/Unwind drums:

Axes coordinates: Essential! MapleSim assumes that the web path is in the XY plane (Z is perpendicular to the plane of the machine)

Diameters: Essential! For simple cases (or for a first-pass model), diameter, inner diameter, length, and material density can be used to calculate mass and inertia of the rollers (and wind/unwind cores).

Length: Is used in visualization.

Inner diameters: Is used in visualization.

Dancer:

Force: Essential! With applicable units.

Position: Essential!

Web properties:

Width: Essential! Is needed also for visualization.

Thickness: Essential!

Controllers: Basic information about the control structure is required. The initial model (Level 1) is created with built-in components.

Level 2 model: The added detail in this phase would be required to ensure the model can be validated against the available measurements through capturing most of the important dynamic features of the web line.

All axes: Pull Rollers, Idle Rollers, Nips, and Wind/Unwind drums:

Density: For simple cases (or for a first-pass model), diameter, inner diameter, length, and material density can be used to calculate mass and inertia of the rollers (and wind/unwind cores).

Inertia and Mass: For more complex shapes, users can choose to enter mass and inertia directly. This is not needed if cylindrical geometry is assumed. A good estimate of roller inertia is important to simulate the effects of web acceleration/deceleration on tension.

Bearing drag: In many cases, this can be ignored. It is more important for low tension usecases.

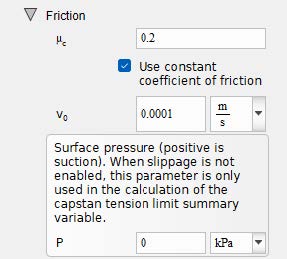

Surface coefficient of friction: If slippage is included in the model, the friction value is an essential parameter (but it may be possible to infer its value from system measurements). If slippage is not included, the friction value is only used to assess the feasibility of the calculated upstream/downstream tension ratio for each roller.

Dancer:

Mass: Required! The total mass (excluding the idler) of the moving parts of the linear dancer is needed to model the effect of acceleration/deceleration (including gravity).

Web properties:

Modulus of Elasticity: When the web is stiff and/or under low tension (i.e. When strains are very small), the overall stiffness of the spans play a small part in the simulation results (unless we are concerned with effects like resonance).

Poisson’s ratio: Similarly, the Poisson’s ratio is important when dealing with stretchy material.

Density: It is needed to calculate the correct inertia of wind/unwind drums but in general it is only a concern for heavier webs or in much more precise conditions.

Sensors:

Load cell: Required! All tensions are available in simulation. Here we just need to know where the load cells are located on the machine. It is important to include the units used in display and the units used in feedback to the controller (if different).

Encoder: Required! All roller speeds are available in simulation. Here we just need to know where the encoders are located on the machine. In simulation we can use "web speed" or "roller surface speed" if there is significant slippage. It is important to include the units used in the display and the units used in feedback to the controller (if different).

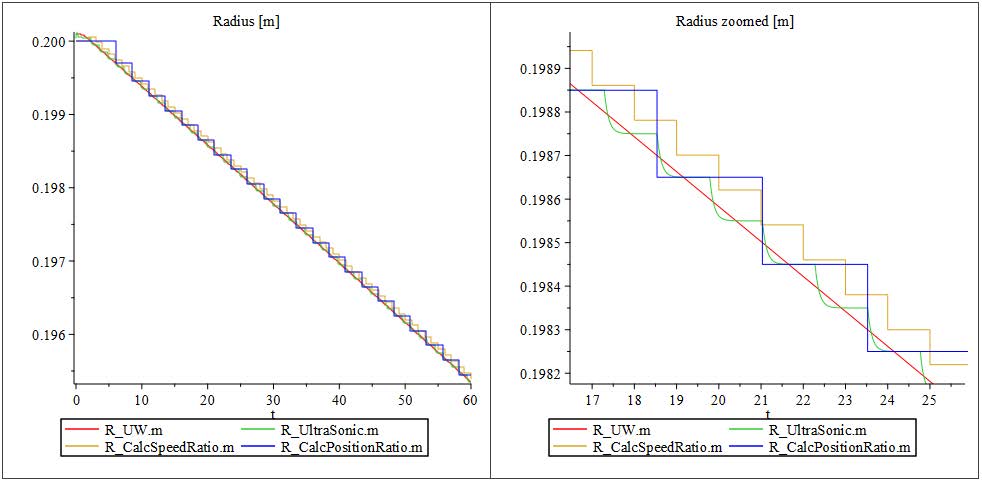

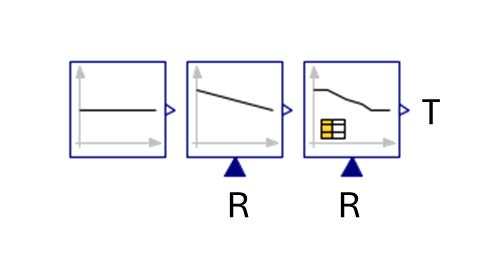

Roll radius: Roll radius is available in simulation. It can also be recalculated from speeds. Information on the actual sensor is needed to replicate the signal used in any controller for higher simulation accuracy.

Level 3 model: Detail study of the system behavior using the Level 2 model may necessitate expanding the model with additional features.

All axes: Pull Rollers, Idle Rollers, Nips, and Wind/Unwind drums:

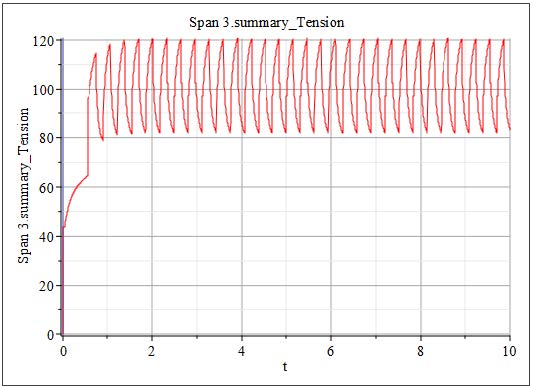

Eccentricity: Optional! If the roller eccentricity effects are to be simulated the user must provide the value of the eccentricity.

Vacuum: Optional! Definition of pressure differences.

Dancer:

Guide friction: Optional! For higher fidelity modeling, guide friction (dry and/or viscous) is required. Of course, this is only implemented if known to be significant or inferred in the model validation phase.

Actuation mechanism: Optional! For higher fidelity modeling, information on the actuation mechanism is required. E.g., piston size, line pressure (or pneumatic circuit).

Actuators:

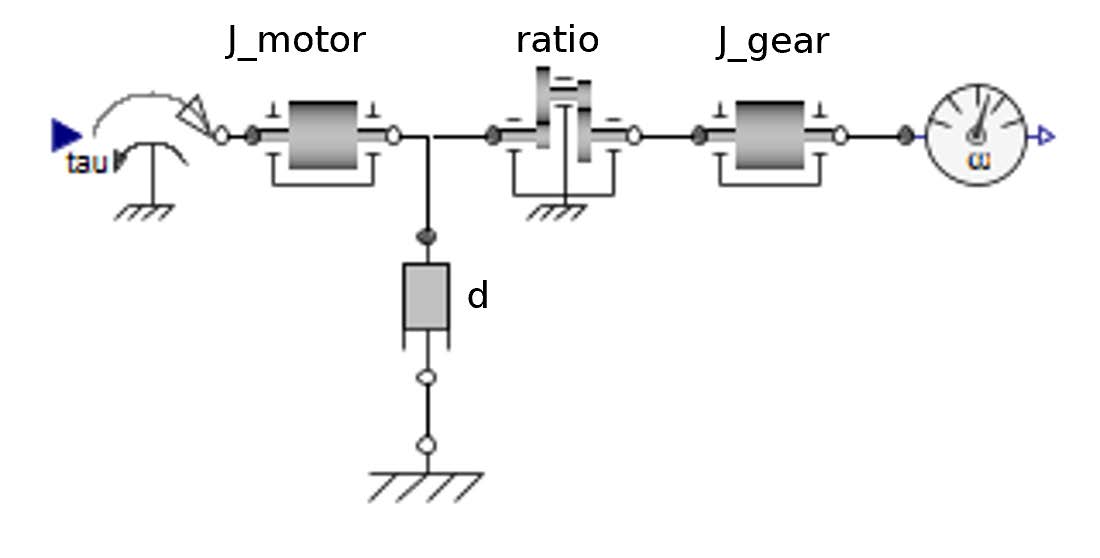

Motor dynamics: Optional! For higher fidelity modeling, motor dynamics can be included. The first step up would be to include a second order dynamics transfer function. If necessary, an underlying speed-controlled motor including drive train can be modeled.

Driveline: Optional! Motor inertia, Gear ratio and inertia, bearing losses can be added to the model.

Controllers: For Level 3 and beyond, detailed information would be needed. This includes controller transfer functions, controller parameters like constant gains or nonlinear gains, limit definitions etc.

Advanced:

Nonlinear web properties: Optional! Where required, MapleSim can incorporate stress-strain data and or Poisson-stress data for a nonlinear web.

Air Entrainment: Optional! Where required, MapleSim can include air entrainment. Required parameters will be discussed later.

A useful model is seldom the most complex model. Not all aspects of the system are relevant to the engineering questions being asked.

Accuracy of the predictions is not an absolute concept. Engineering questions may be answered adequately with approximate simulation results.

Model deviation from reality can be attributed to many different sources:

Intentional simplifications (e.g. neglecting material nonlinearity due to a lack of data)

Unknown physics (e.g. variation in the air pressure due to outside systems)

Physics not supported (e.g. material variation in MD/CD, misalignment)

Unknown/guessed system parameters (e.g. a guessed value for the bearing friction)

Here are some general modeling tips. This is an overview and the single points will be discussed in the following training chapters.

Elasticity: Start with a linear (constant) Elastic Modulus.

Material damping: Use the default material damping. Adjust as needed. In the most cases the default value is never changed.

Density: An exact value is rarely important. Example cases are modeling slack and high acceleration/deceleration motions.

Averaged values (in all directions) should be used. Non-uniformity is not modeled.

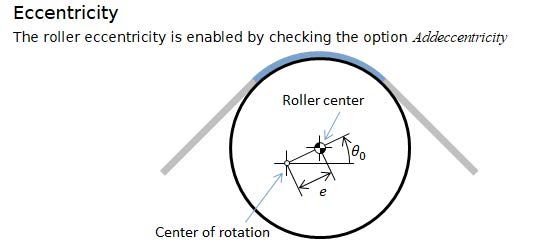

Slippage is often an issue for real machines and must be considered in simulations. But there are different levels of detail which increases the computation effort of a model. Start always from simple to more complex models. Consider all rollers in the first simulations as non-slipping rollers and check the summaryLimit result of each roller. Is there a chance of slippage? In which operations? Can it avoid with changed controller settings (e.g. start up ramps)? If not, slippage should be actively calculated with the checked feature of the considered rollers. High speed applications can be influenced from air entrainment which is the next level of detail.

Bearing losses can normally be ignored. The default setting is zero. It can play an important role for applications with low tension levels of with a lot of idle rollers. In this case it is easy to highlight all rollers and change the value for all of them in the same time.

Ideal rollers without imbalance or eccentricity are the default rollers in a model. Add disturbances if the task it to analyze the influence of such disturbances.

Default –> Stepwise winding/unwinding considers the impact of the layer change during winding or unwinding.

Default –> Eccentricity models the same effect as in rollers.

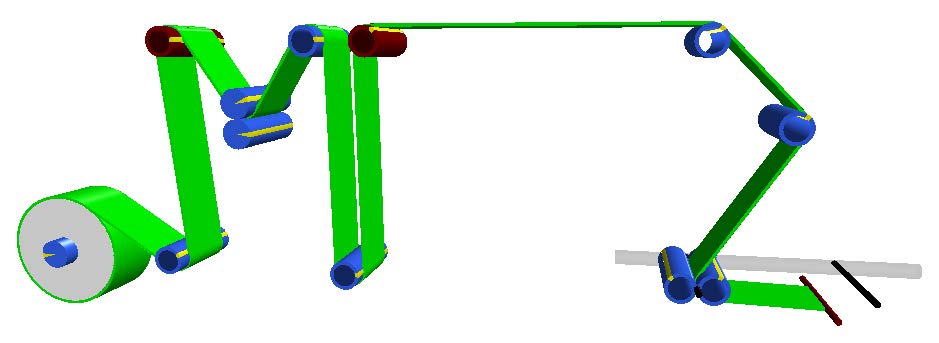

MapleSim provides the flexibility to model moving rollers in combination with other dynamic mechanical components (such as levers), to define their direction of motion collectively referred to as dancers. This enables users to design and simulate a wide range of dancer systems, including linear and rotational dancers. These dancer mechanisms can be modeled as either passive systems, driven solely by gravity or mechanical constraints, or as active systems, actuated by technologies such as pneumatics, hydraulics, or electric motors. These dancer models are particularly useful for tension control applications within roll-to-roll (R2R) processes. They can dynamically respond to changes in web tension, compensate for disturbances, and maintain stable operation during transient conditions such as machine start-up or shutdown. Through simulation, MapleSim allows users to extract a variety of critical measurements depending on the model configuration. These include:

Web tension across individual spans

Span lengths and their variation

Roller dynamics and position changes etc.

Dancers that are actuated often are actuated through pneumatics - force from a pneumatic cylinder, or torque from an electric motor. Both forms of actuation keep a desired tension on the web around the dancer roller.

In this first example we will build a simple rotational dancer in MapleSim.

The figure below provides an overview of the model that will be built in this section:

Figure 3.1: Model schematic of simple dancer

Open a new MapleSim model and save as “SimpleDancer.msim”

Add the following Web handing Library components to the canvas:

Web Properties - W =0.2[m]

1 Web Source

4 Spans

3 Rollers

1 Web Sink

in Web Handling > Primitives : 1 Fixed Frame and 1 Revolute

Add the following Signal Blocks to the canvas:

1 Constant block

2 Poly Ramp blocks

1 Sine Source block

1 Add block

Connect all the components on the canvas as can be seen in Figure 3.1 below

For the various components in the model (from right to left) fill in the corresponding parameters:

Constant - k =100

Web Source - Check Use Fixed Base use default position r =[0,0]

Check Use Fixed Base

L=0.25[m]

base position for Roller 1 : r =[0.5,0][m]

base positioin for Roller 3 : r =[0.9, 0][m]

Check Use alternative configuration

Di=0.15[m]

L=0.25[m]

Under Frame section enter frame mass mf =10[kg]

Check Add Frame Offset

For frame offset, set to rf =[-0.3,0][m]

Revolute - Change IC to be Strictly Enforce keep the IC values as default (Both 0)

Fixed Frame - position r =[1,-0.7][m]

Web Sink - Check Use Fixed Base and input position r =[1.4,0]

Sine Source - A=0.2 and T0=4[s]

Click ‘Run Simulation’ (![]() )!

)!

Figure 3.2: 3D view of a simple dancer model

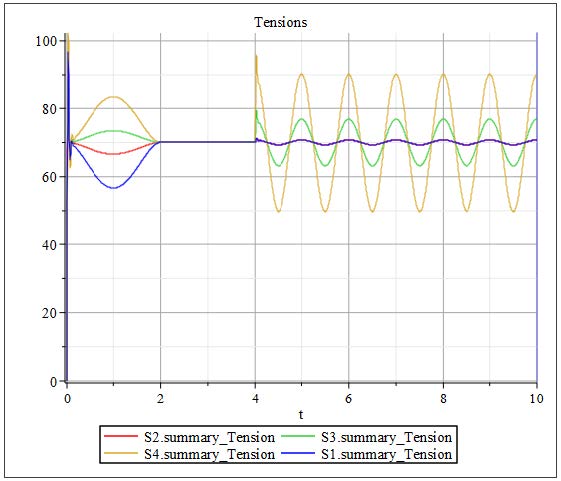

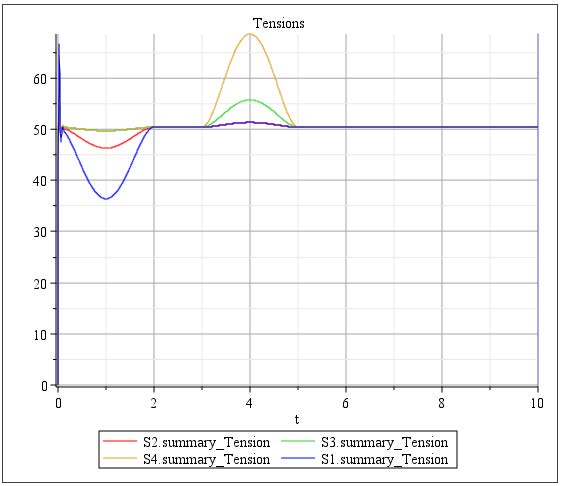

By introducing a Sine Source into the web line, there are some disturbances that will affect the tension as can be seen in Figure 3.3

Figure 3.3: Simulation results of tensions from simple dancer model

The tension plot reveals key insights into the system’s dynamic behavior. During the first 2 seconds of the simulation, the acceleration of the web line overcomes the inertia of the rollers, resulting in noticeable fluctuations in tension across the spans. This is a typical transient response as the system adjusts to the initial motion. By the 2-second mark, the line reaches a steady velocity, and as a result, the tensions in each Span stabilize, converging to a nearly constant value of approximately 70 [N].

At 4 seconds, a disturbance is introduced in the downstream velocity, which significantly impacts the tensions, particularly in Spans 3 and 4. The dancer, which is free to rotate about its pivot point, plays a crucial role in mitigating these effects. Its ability to pivot allows it to absorb and compensate for the tension fluctuations caused by the velocity disturbance.

Specifically, when the downstream velocity signal peaks, the web is pulled more strongly, causing an increase in tension and prompting the dancer arm to pivot upward. Conversely, during drops in velocity, the tension decreases, and the dancer arm moves downward to maintain balance. This dynamic motion helps regulate upstream tension. As a result, Spans 1 and 2 experience smaller variations in tension compared to Spans 3 and 4, highlighting the dancer’s effectiveness in buffering disturbances and maintaining tension stability on the upstream side.

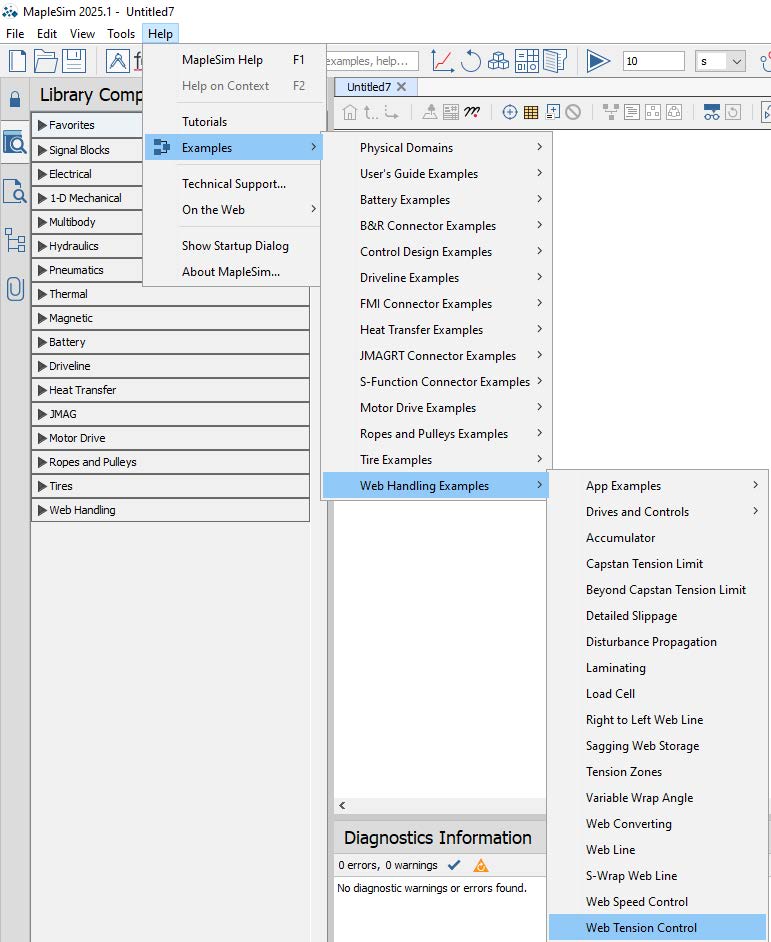

An example "Web Tension Control" can be found in the MapleSim example palette under Web Handling category. This example model demonstrates feedback control for a dancer arm.

Figure 3.4: Location of example in MapleSim

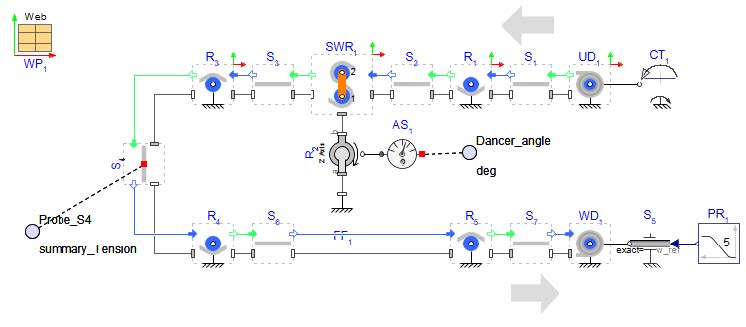

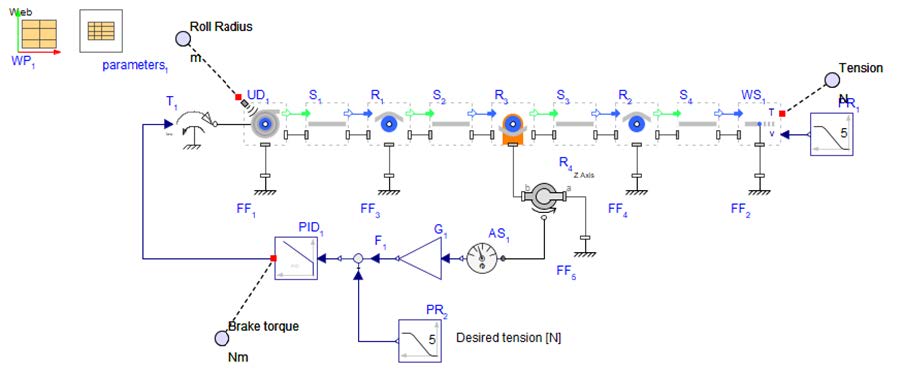

The model shown in Figure 3.5 incorporates a controller that uses feedback from the dancer arm angle, combined with a predefined tension input, to regulate the torque applied to the unwind drum. Additionally, the revolute joint in this example is configured with specified torsional stiffness and damping, as well as angle compensation to account for the weight of the dancer arm.

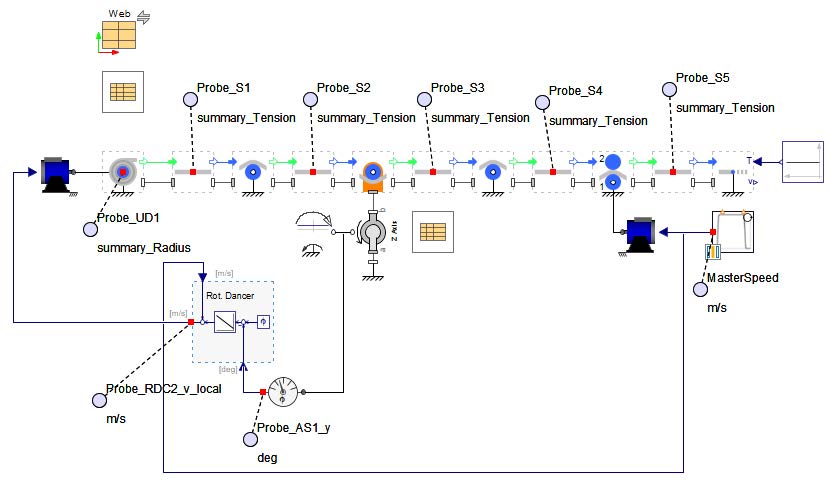

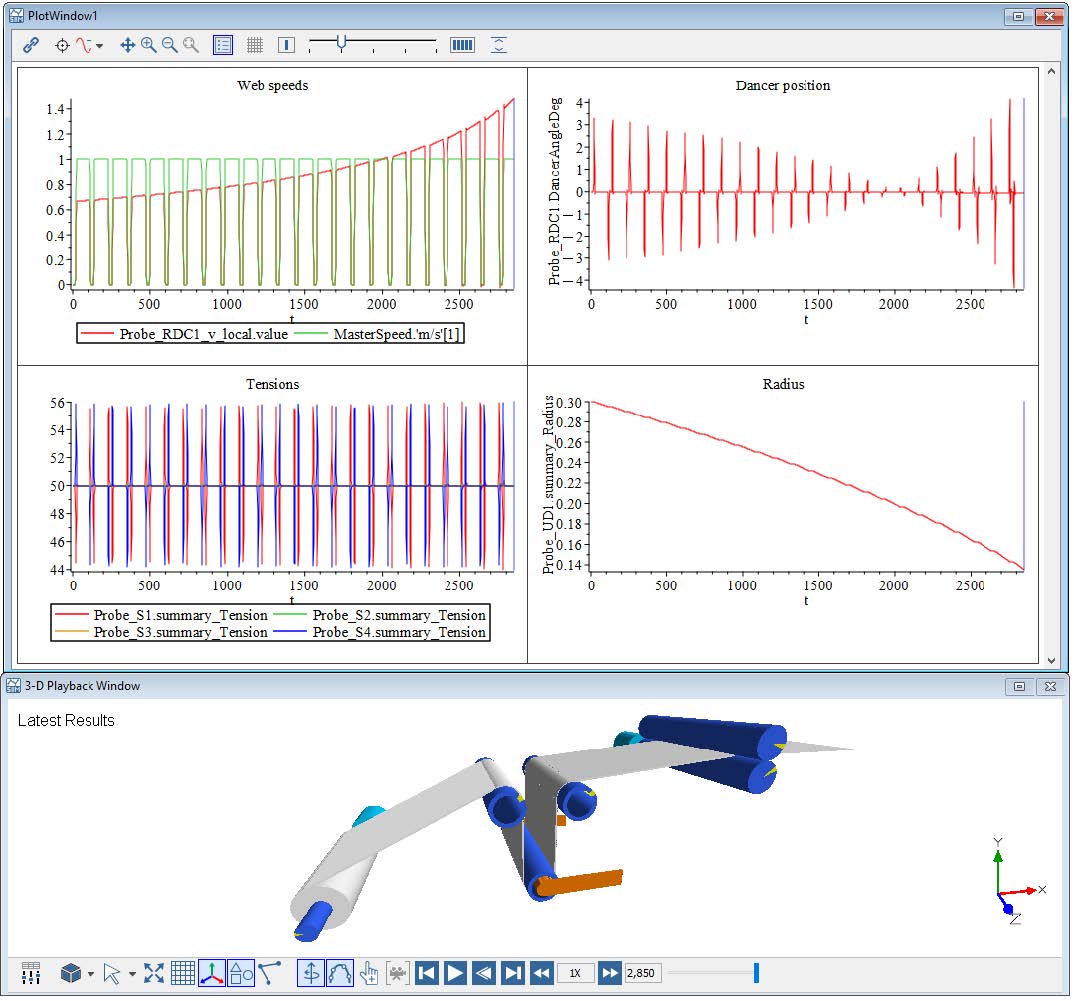

Figure 3.5: Tension Control model schematic

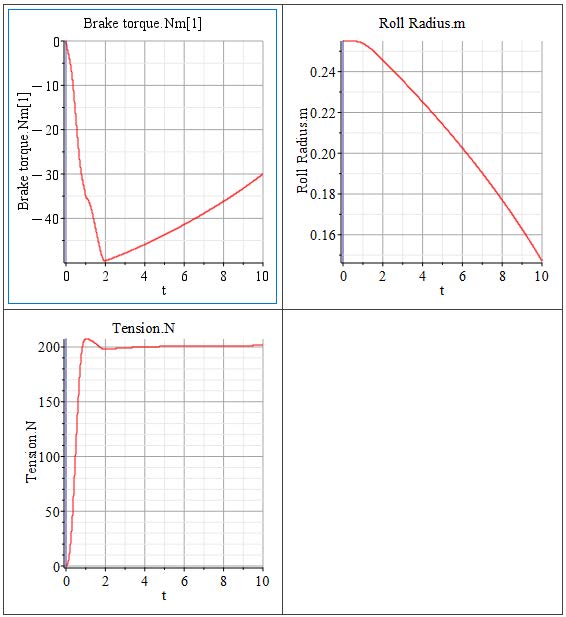

The simulation results shown in Figure 3.6 illustrate the system maintaining a target tension of 200 [N]. The braking torque is regulated by a PID controller, using the dancer arm angle as feedback to keep the web tension at the desired level. The output tension exhibits minor fluctuations around the 200 [N] target, reflecting the dancer arm’s continuous adjustment to stabilize the unwind web tension.

Figure 3.6: Simulated results from Tension Control dancer model

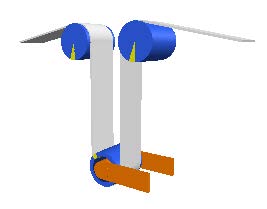

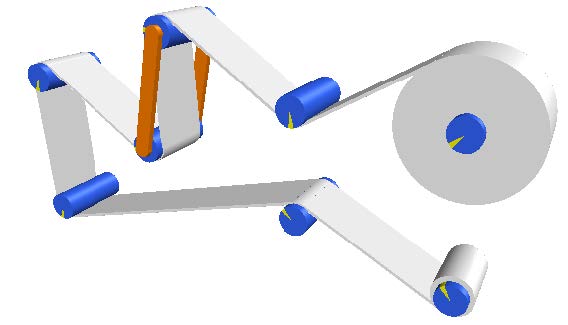

A rotational dancer is made up of two connected, movable rollers that pivot around a central point. In MapleSim, this is modeled using a Revolute joint from the Web Handling > Primitives , connected to a Fixed Frame , allowing rotation around the center point between the two Rollers that form the S-Wrap Roller .

The figure below provides an overview of the model that will be built in this section:

Figure 3.7: Structure of a rotational dancer model

The Web Sink uses either speed input or tension input signal, for this model the Web Sink will use the Tension input mode. There is a constant tension of 100[N] with an additional sine source disturbance.

This disturbance is activated after 3[s].

This model is using a feature of the WebHandling library that assigns color to the web based on a minimum and maximum tension value. The option (Use tension) can be selected in the WebProperties component under the section Visualization . The user can define a color and a value for the minimum and maximum limit - in this example Green (80[N]) and Red (120[N]).

Now, Click ‘Run Simulation’ (![]() )!

)!

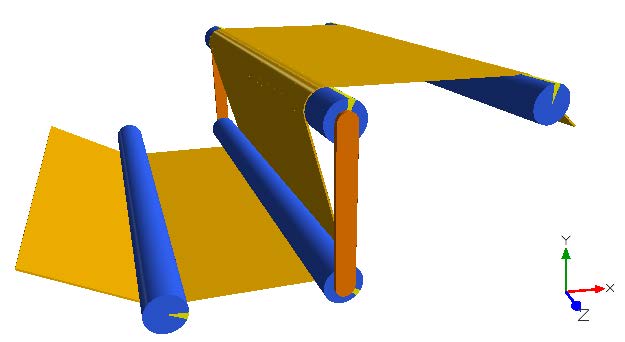

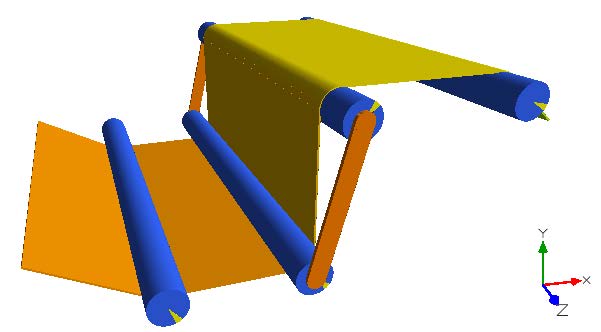

First look at the 3D Animation view Figure 3.8. Based on the disturbance, the color of the web changes.

Figure 3.8: 3D view with coloring of the web spans

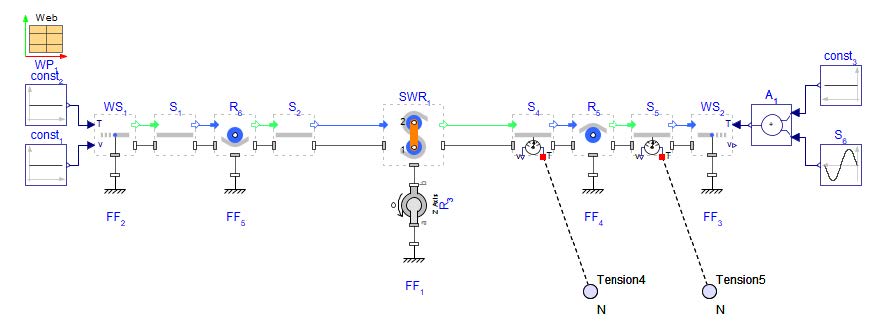

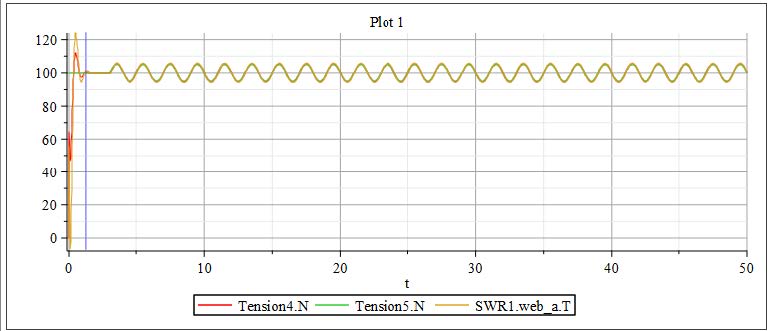

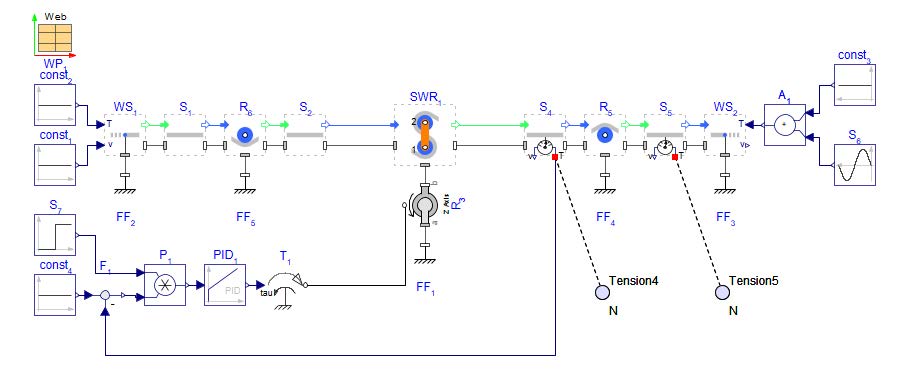

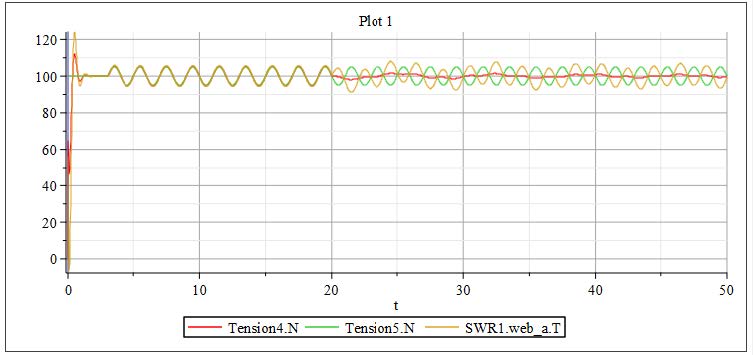

The model includes two probes (Figure 3.7) that measure the tension in Spans 4 and 5. Additionally, the tension within the Span located between the two rollers of the S-Wrap Roller is captured and displayed in the results window. Figure 3.9 presents the tension results for each span, labeled as Tension4.N, Tension5.N, and SWR1.weba.T . After the initial startup phase, the tension remains steady until 3 [s], when a disturbance is introduced—resulting in visible sinusoidal fluctuations across all three tension signals.

Figure 3.9: Tension diagram

Now we will control the dancer and reduce the disturbance in the Span 4 by implementing a control in the model.

However, we strongly encourage to go through the steps to built the model from scratch. The below figure shows the outline of the downloaded model. Figure 3.10 shows the model structure.

Figure 3.10: Structure of a controlled rotational dancer model

To build the above model, lets first start with the base model used in the previous section without the controller added Figure 3.7.

Add a Torque component from the 1-D Mechanical > Torque Drivers palette and connect it to the Revolute .

Add a PID controller, a Feedback , a Step and a Constant from the Signal Blocks > Common palette.

Add a Product from the Signal Blocks > Mathematical > Operators palette. Normally this is not needed but in this case it is used to activate the controller at a prescribed time. This allows for comparing the model results in the state that it was in previously to the controlled state that is being built in this model.

Change the following parameters:

Constant : k = 100[−]

Step : T0 = 20[s]

PID : k = 100[−]

PID : Ti = inf[s]

PID : Td = 0[s]

Connect the components as shown in Figure 3.10 and close the control loop.

Click ‘Run Simulation’ (![]() )!

)!

The 3D Animation (Figure 3.11) shows that the controller works well. Span 4 has nearly the same color after the controller is applied, after 20 [s].

Figure 3.11: 3D view with coloring of the web spans

The curves in the diagram depicted in Figure 3.12 show the disturbance reaction starting at time 3[s] and the result of the controlled dancer at time 20[s] at which point the controller damps the tension seen in Span 4.

Figure 3.12: Tension diagram

Another example that is similar to the previous two examples an S-Wrap Dancer. This example is available to be explored for self-study in the MapleSim example palette under Help > Examples > Web Handling Examples > Right-to-Left Web Lines.

Figure 3.13: 3D view of S-Wrap dancer example in MapleSim

Accumulators—also known as buffers—function similarly to dancers, but their primary purpose is to store or release web material during line operation. This enables flexibility in handling varying speeds between sections of the web line, such as between the process and the winder. Unlike dancers, which primarily regulate tension, accumulators manage material flow and help maintain continuous operation. They can be either passively driven by gravity or actively driven using motors or other actuators.

MapleSim enables full customization of motion profiles, tension measurement from the accumulator’s entry to its exit, and visualization of the carriage’s movement. Additionally, you can explore the impact of bearing drag, detect potential web-to-roller slippage, and analyze other key dynamics within the accumulator system.

In the following example a simple accumulator will be built as shown in Figure 3.14.

However, we strongly encourage to go through the steps to built the model from scratch. The below figure shows the outline of the downloaded model.

Figure 3.14: MapleSim schematic of a simple one roller accumulator.

Download a start model for this section SimpleAccumulator_start.msim

The schematic of the downloaded model is shown below. We are now going to make this model function as an accumulator.

Figure 3.15: MapleSim schematic

CLick on the Roller R2 and uncheck the Use fixed base option.

Insert a Fixed Frame and Rigid Body and Prismatic. from Web Handling > Primitives and make the connections as shown in the Figure 3.14.

Change the Prismatic Axis from x-axis to y-axis.

Set the IC in the Prismatic to Strictly Enforce and keep the initial conditions at s0=0 [m] and v0=0 [m/s].

Change the Fixed Frame position to r = [0.7,-0.2]m. Connect the Fixed Frame to the Prismatic .

For Roller 2 , Set the frame mass in Roller 2 to be mf =0[kg] since this is a hanging Roller and there is no frame attached. Ensure Roller frame mass is properly accounted for when there is a hanging Roller in a system, i.e. mass=0[kg]

The signal input to Web Sink velocity needs to be updated to the following:

top Sine Source block needs to be replaced with Poly Ramp component, PR2 and update the following -

height =1.3

T0=3 [s]

bottom Poly Ramp component PR3 -

height =1.3

T0=10[s]

Click ‘Run Simulation’ (![]() )!

)!

Figure 3.16 shows the tensions in each web span . The results can be broken down into various zones based on what is happening in the system.

Figure 3.16: Plotted tension results of simple accumulator system

Question: How does changing the value of the mass in the Rigid Body affect the tensions of the system?

Accumulators are usually larger systems that consist of more Rollers and more elaborate frames or carriages as can be seen in Figure 3.18. There are two examples of larger accumulator systems. The first is a passive buffer.

The below figure shows the outline of the downloaded model.

Figure 3.17: Model overview

Figure 3.18: 3-D view of passive accumulator

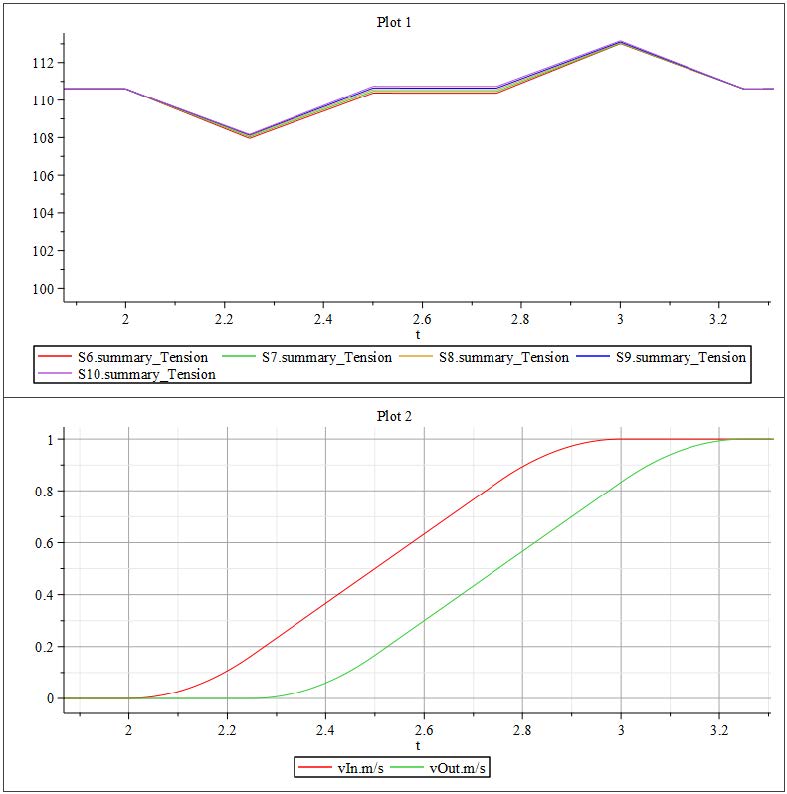

Figure 3.19: Zoomed in results of tension and velocity plots from Passive Buffer model

Figure 3.19 shows a zoomed in section of the simulation results for tension and input/output velocities. There is a noticable reaction in the Span tensions in this system to web line velocities. The acceleration at t=2[s] result in lower tensions as the velocity of the line increases. The downstream velocity is offset by 0.25[s] and once the output velocity increases at t=2.25s, the tensions in the Spans increase. The tensions increase until the velocities become constant, resulting in constant tensions.

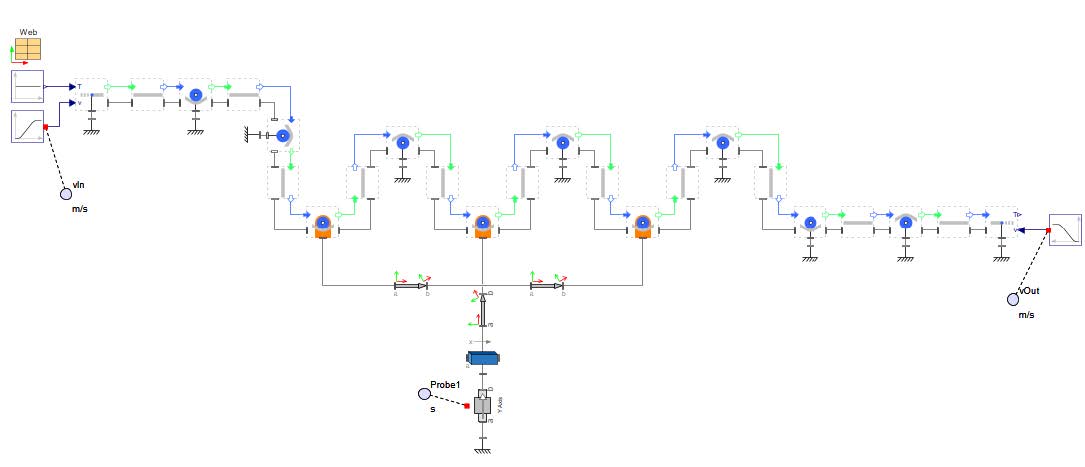

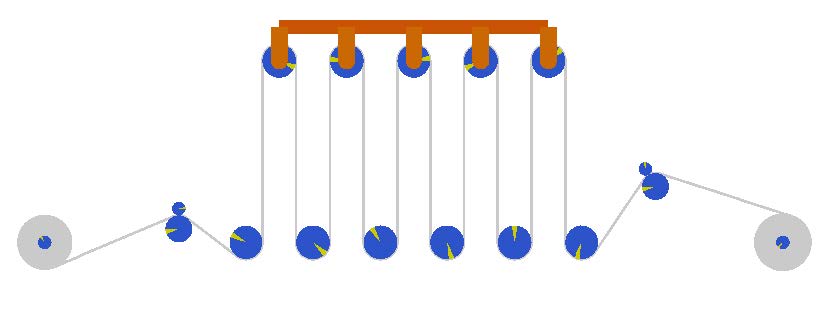

The second example is found in MapleSim Example Palette available for self-study (the first model listed under Web Handling Examples titled “Accumulator.msim”). This is a more detailed example of a driven accumulator, as can be seen in Figure 3.20. The line has two driven Nip Rollers at either end of the accumulator that are motor driven with input/output speed profiles (created using the 1-D motion generation app). There is a detailed breakdown of the MapleSim model on the canvas for that example.

Figure 3.20: MapleSim Example of a more complex accumulator system

A few examples will be covered under the topic of web converting: Laminating - taking multiple webs and merging them into one web, Converting - the actual converting of one web to another web utilizing conservation on mass (e.g. glue is added to a cardboard web), and Discontinuous changes that has an in-going web of specific properties and an outgoing web of another property without the conservation of mass (e.g. part of the web may have been cut away).

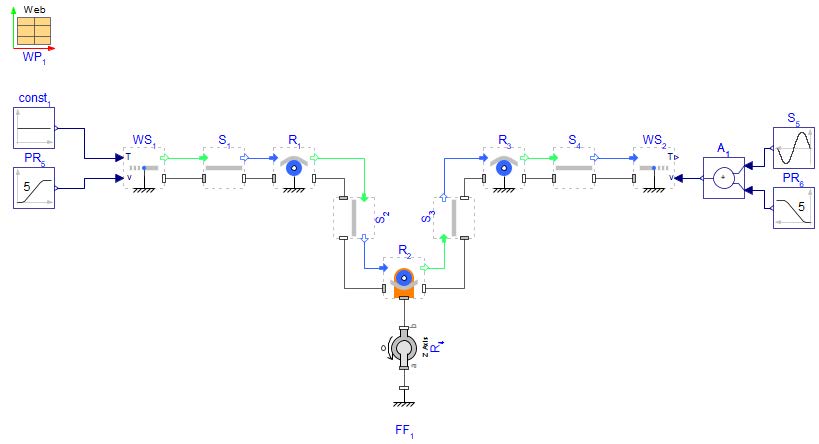

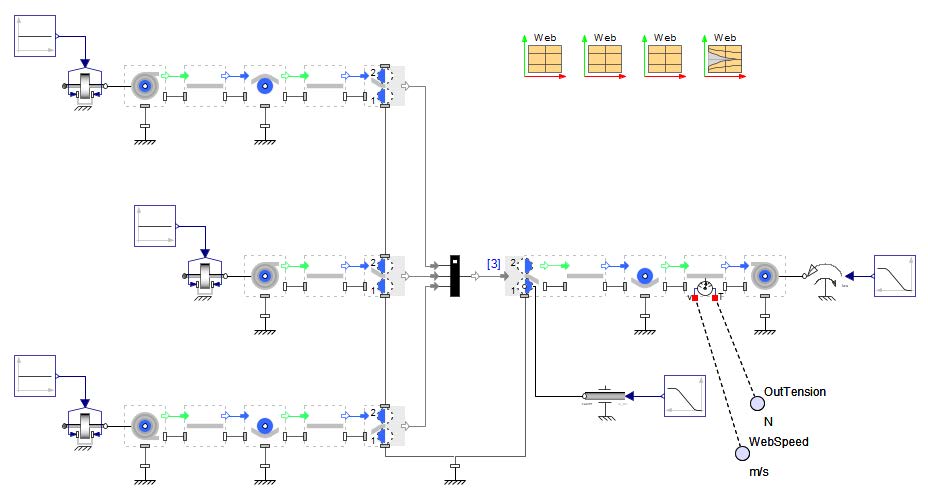

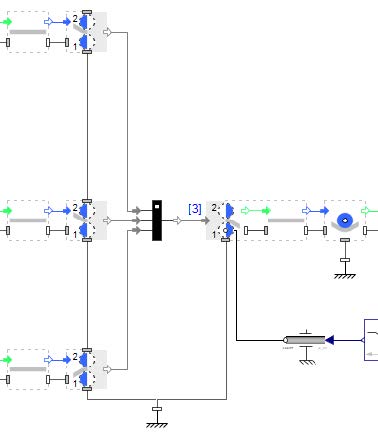

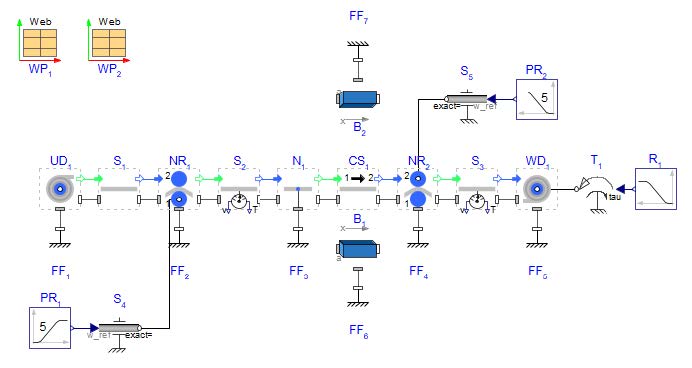

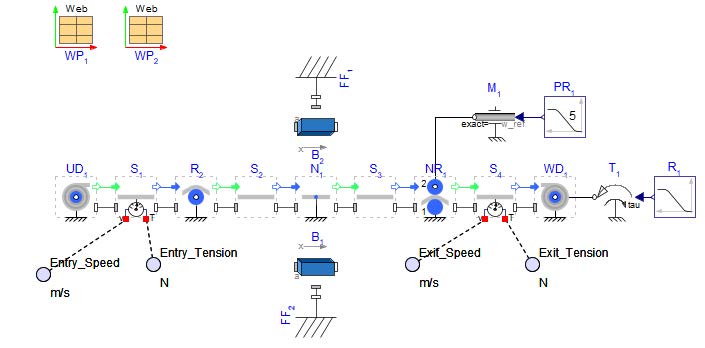

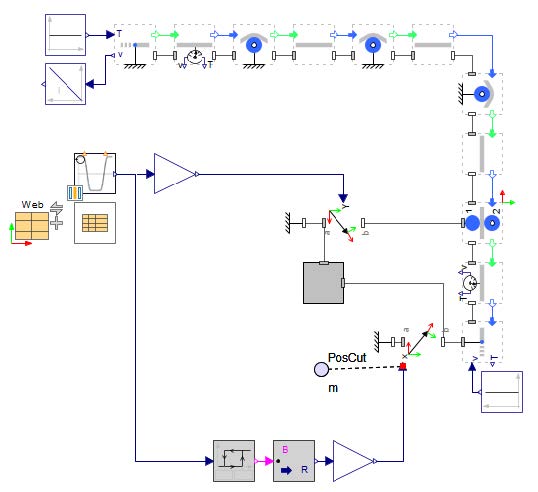

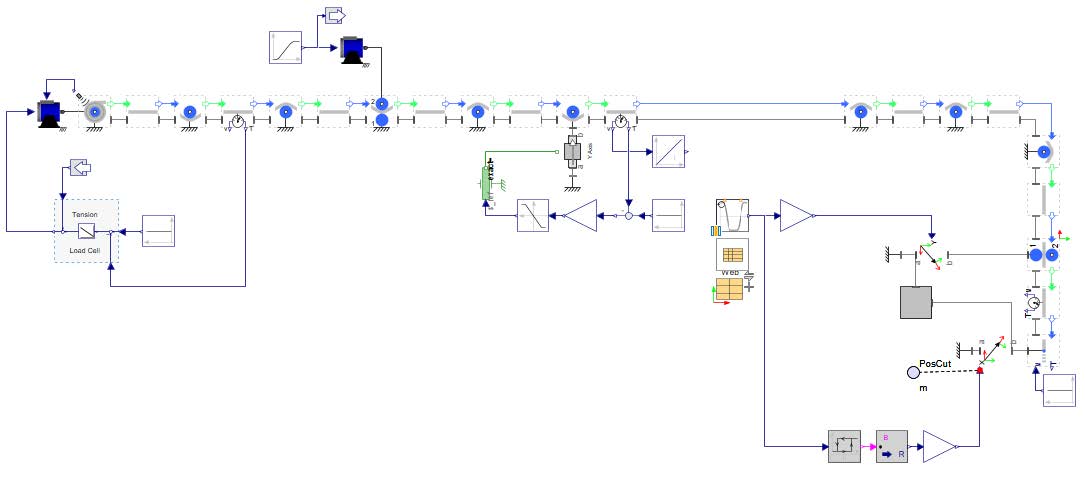

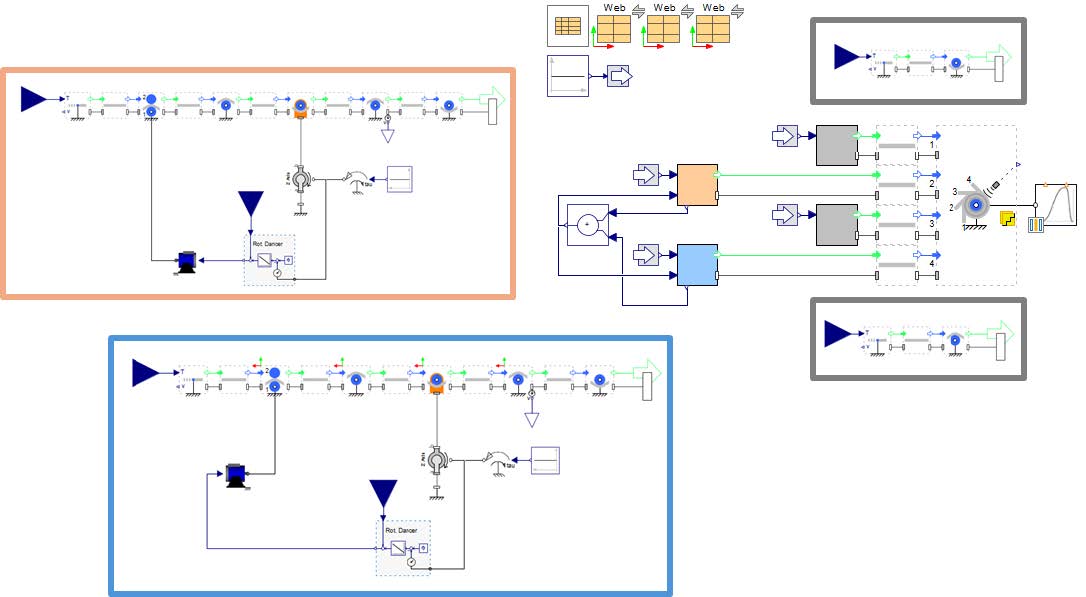

In this section the built-in MapleSim example model “Laminating.msim” is discussed to get a deeper look at the components used and its parameterization. This model contains three separate lines as input to the laminating point, shown in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1: Structure of the laminating model

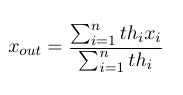

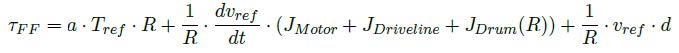

There are three Web Properties components to define the web properties of each line. The laminated web needs a definition of its properties as well, this is defined in the component called Merged Web Properties located in Web Handling Libaray > Laminating . This new component calculates a merged value of each parameter from the input webs. A definition of the merged webs is needed for this component, such as: MergedWebProperties = [WP1, WP2, ...]. The order in which the individual Web Properties are entered into the Merged Web Properties should correspond to the order of the actual web. The formulas for the component are written out in the associated Help page. The main formula for the parameters is written in equation (??) where x is a place holder for a parameter and i is the the i-th incoming web.

Figure 4.2: Merged Web Equation

Figure 4.3: Structure of the laminating part in the model

The lamination process is modeled by several components. The last Span of each in going web line must connect with a separate Multi Web Roller In component as shown in Figure 4.3. The output signal of each Multi Web Roller In component is the input signal of the Multi Web Roller Out . This element expects a vectored input signal (see the printed [3] in Figure 4.3). A solution for that is the use of a Web Multiplexer component. The Multi Web Roller Out contains a roller pair with a span section (Figure 4.4). This component needs information about the Web Properties of the incoming and the outgoing merged web. A Roller or Web Sink component must be connected after the Multi Web Roller Out before attached to another Roller in the system.

Figure 4.4: Scheme of the model approach of the Multi Web Roller Out

The Unwind Drum is connected with a rotational Brake from the 1-D Mechanical > Rotational > Clutches and Brakes package. This leads to a tension force on the outgoing web of the Unwind Drum. The Wind Drum is driven by a Torque source from the 1-D Mechanical > Rotational > Torque Drivers package. This allows for pre-tensioned of the web line within the first second of the simulation.

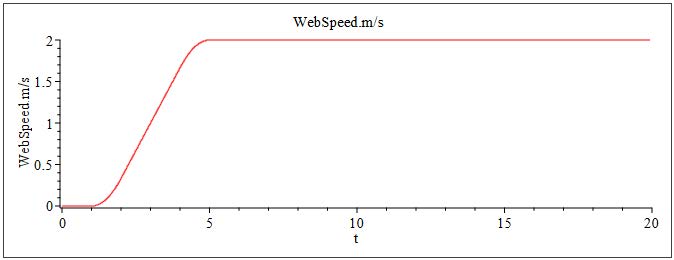

One of the Rollers within the Multi Web Roller Out is driven with a speed driver. The drive startup for this example model happens from 1 to 5[s] as shown in Figure 4.5.

Click ‘Run Simulation’ (![]() )!

)!

Figure 4.5: Results: Plot of the web speed

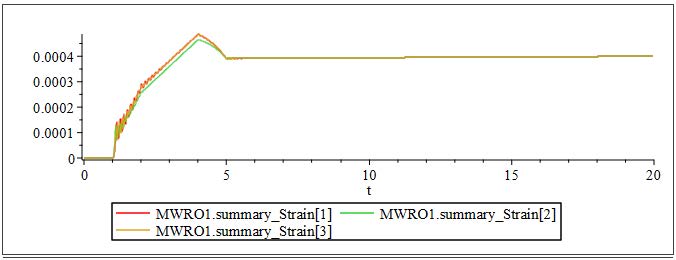

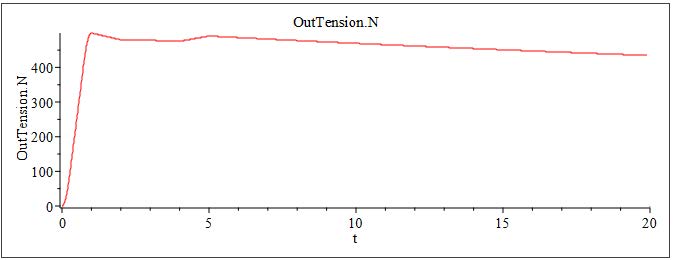

Figure 4.6 presents the curve of the strain of the in-going web lines at the lamination point. There are some observable oscillations during the startup phase. After start up time of 5 [s], the web line obtains a constant speed. The strain increases slightly over time as the radius of the Unwind Drum components decrease. On the other side (Wind Drum ), the tension in the Span (Figure 4.7) decreases after the startup phase. This decrease is due to the constant torque Wind Drum drive and the increasing radius.

Figure 4.6: Results: Plot of the strain of the in-going web lines

Figure 4.7: Results: Plot of the tension of the last span

Converting web is when a web undergoes a change in material properties while still conserving mass. Some examples are: calendaring (when a single material is squeezed), flutting (when a single material is ridged), or drawing (plastic deformation). The example model that will be analyzed for this section is from the MapleSim example platte called “WebConverting.msim”, open from the help menu in MapleSim. Schematic shown in Figure 4.8.

Figure 4.8: MapleSim canvas schematic of web converting example

As mentioned in the introduction to this chapter, web converting considers a web of specific properties, and then converts it to a web of new properties. As such, the model needs two Web Properties components and each Span, Roller, Wind/Unwind drum, Web Source, Web Sink etc. needs to be referenced to the correctly intended Web Properties to achieve desired results. A component called a Converting Span should be used in the location of the web line where one web property is converted to another web property. This component can be found in Web Handling Library > Webs. In Figure 4.8, there is another component used called a Node also found in Web Handling Library > Webs. The Node component models an ideal (zero radius) roller with an optional speed input (not used in this model). The Node in this example allows for a defined point in the web line and is used to set the length of the Converting Span range.

Figure 4.9: 3D visualization of converting web model

In Figure 4.9, the modulus of elasticity and the thickness of the web is changed - the web enters with web properties of WP1 in blue and exits with properties of WP2 in pink. The thickness of WP2 is half that of WP1 and the modulus E of WP2 is a quarter that of WP1.

Figure 4.10: Simulation results of web converting model

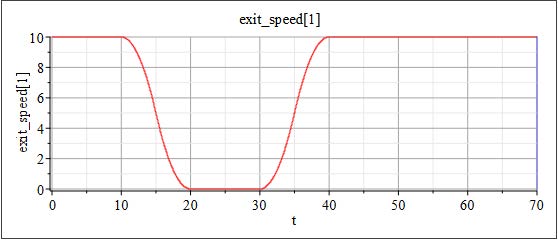

This model follows the conservation of mass as part of it’s governing equations below, as such the upstream and downstream velocities have to be adjusted to obey the equations. From Figure 4.10, the exit speed is twice that of the entry speed.

Figure 4.11: Conservation Equation

Discontinuous change is when any material is added or removed from the web without laminating, this would include processes such as drying, printing, adding glue, cutting, stamping, etc.

Figure 4.12: MapleSim schematic of web cutting model

In this example (Figure 4.12), a web is being cut. The width of the web is reducing from 0.2 [m] to 0.1 [m]. A few assumptions and simplifications to note: there is no actual cutting action being modeled, there is no affect from the scraps, the model does include visualization of cutting bricks (boxes shown in Figure 4.13) but it is purely visualization, and asymmetrical cutting is unable to be modeled at this time. Only the mechanical properties of mass per unit length and stiffness, due to change in width, change from one Web Property to the other.

Just like the examples above, there will need to be multiple Web Property components used for the number of changes to the web that will be occurring in the modeled section of web line. This example only changes properties once so there is only WP1 and WP2. If the width is change as it is done in this example the parameter Width option of span S3 has to be changed to Downstream.

Figure 4.13: 3D visualization of web cutting model

It can be seen in the tensions seen at the entry Span 1 increases while the exit Span 4 decreases. This comes from the lack of tension control in the web line as well as the changing radius of the drums.

Figure 4.14: Simulation results from web cutting model

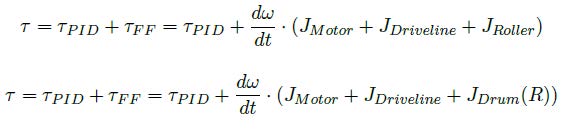

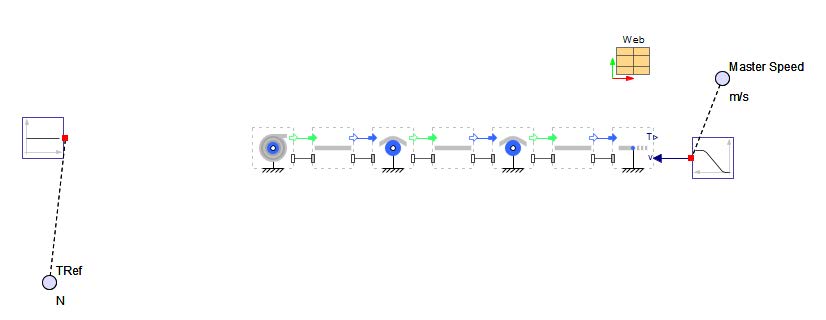

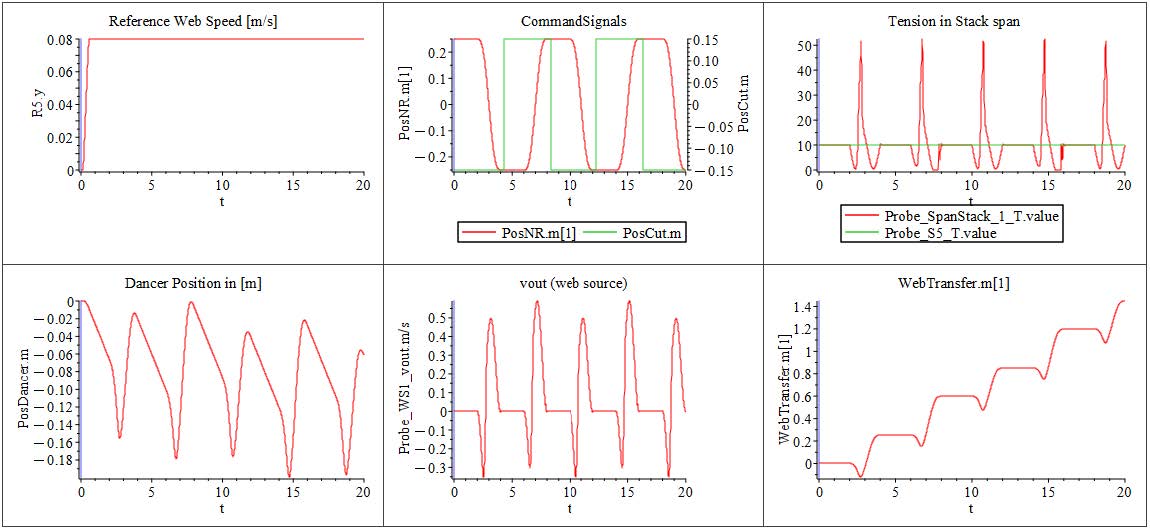

The Web Handling: Drives and Controls sub library offers a straightforward approach for defining speed profiles and implementing tension control loops in roll-to-roll processes. It allows users to efficiently organize the web line model and supports the testing and fine-tuning of control parameters in a clear and structured way.

A common method used with PLCs for tension control involves adjusting the speed of a roller or winder. In this approach, the tension controller modifies the local web speed within the web line to regulate tension levels. Feedback for the controller may come from a load cell providing direct tension measurements, or from angular or positional sensors connected to a rotational or linear dancer system.Typically, the adjustment range for the local web speed is limited to around 5–10

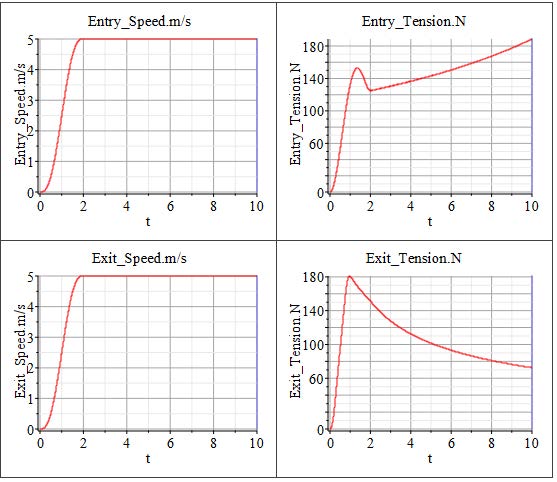

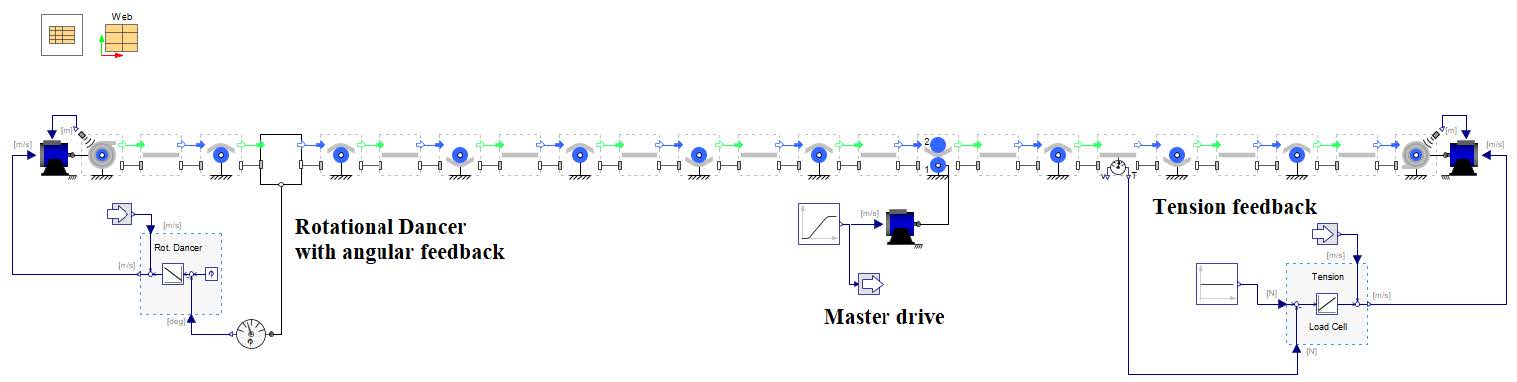

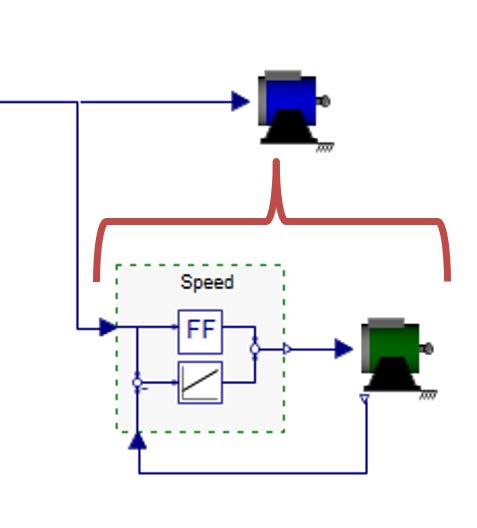

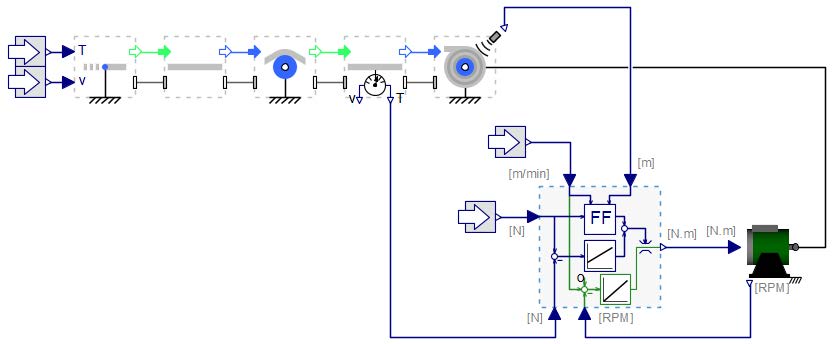

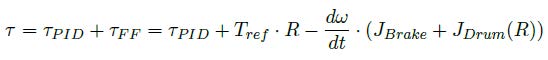

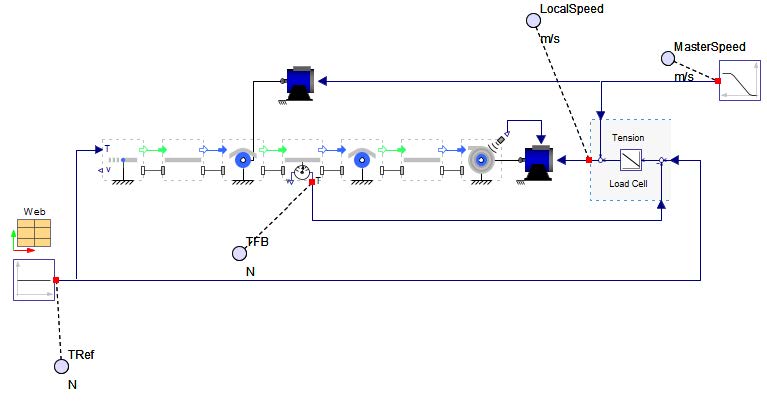

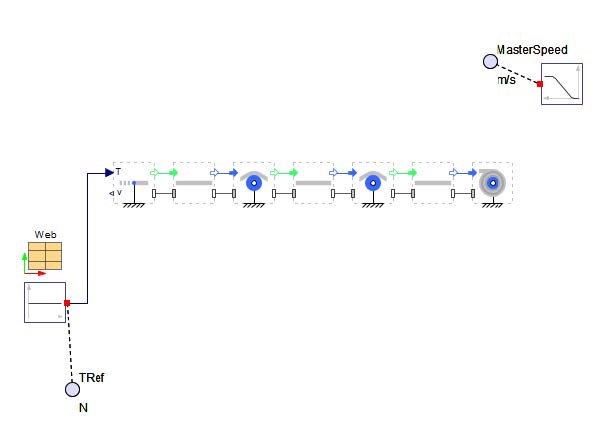

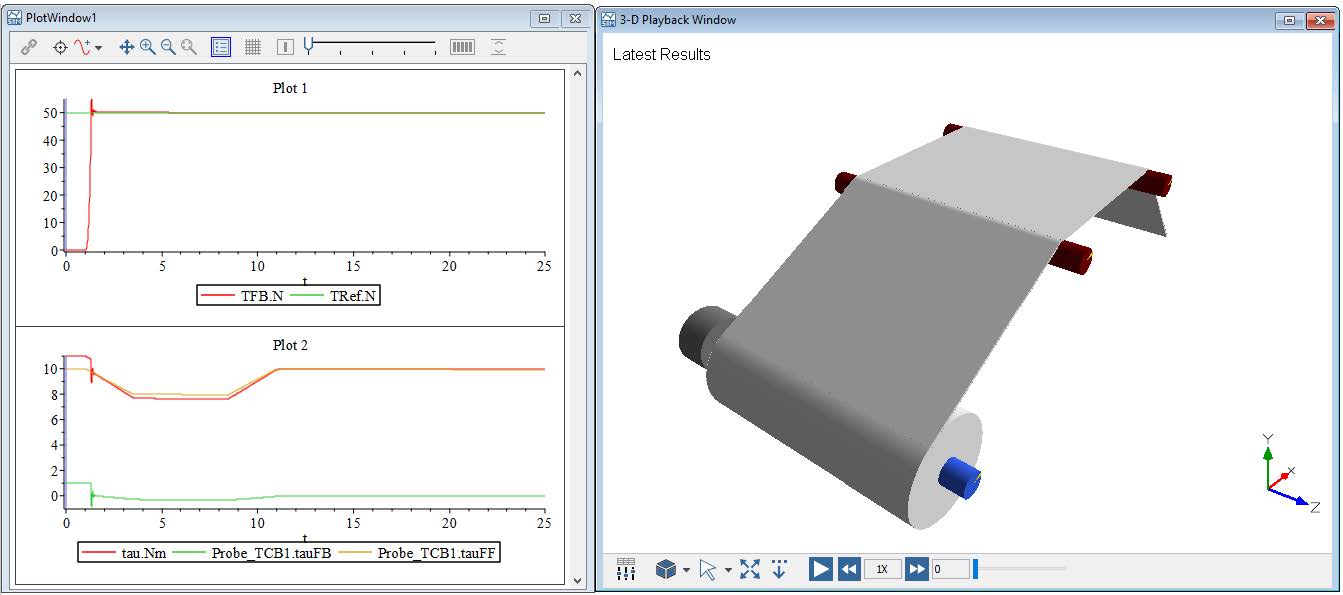

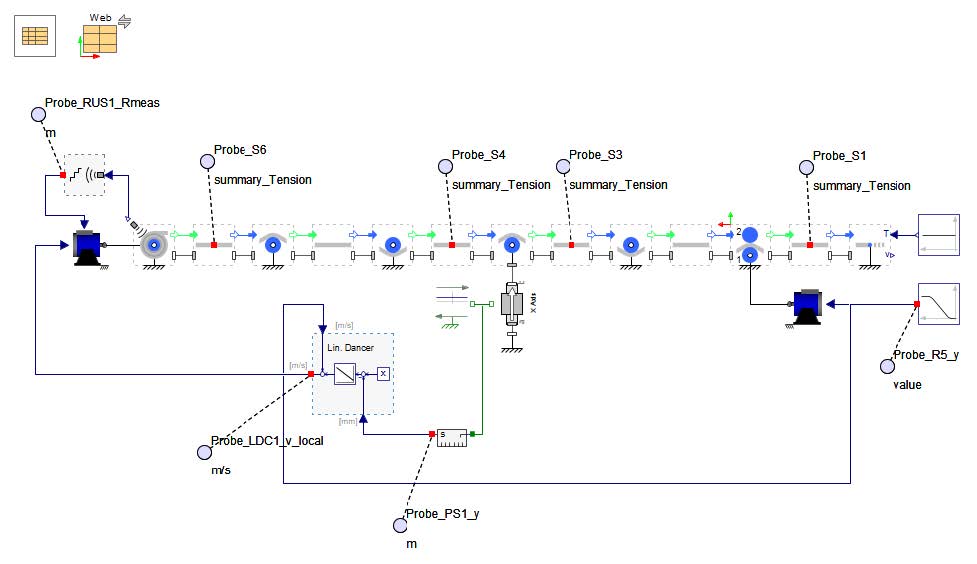

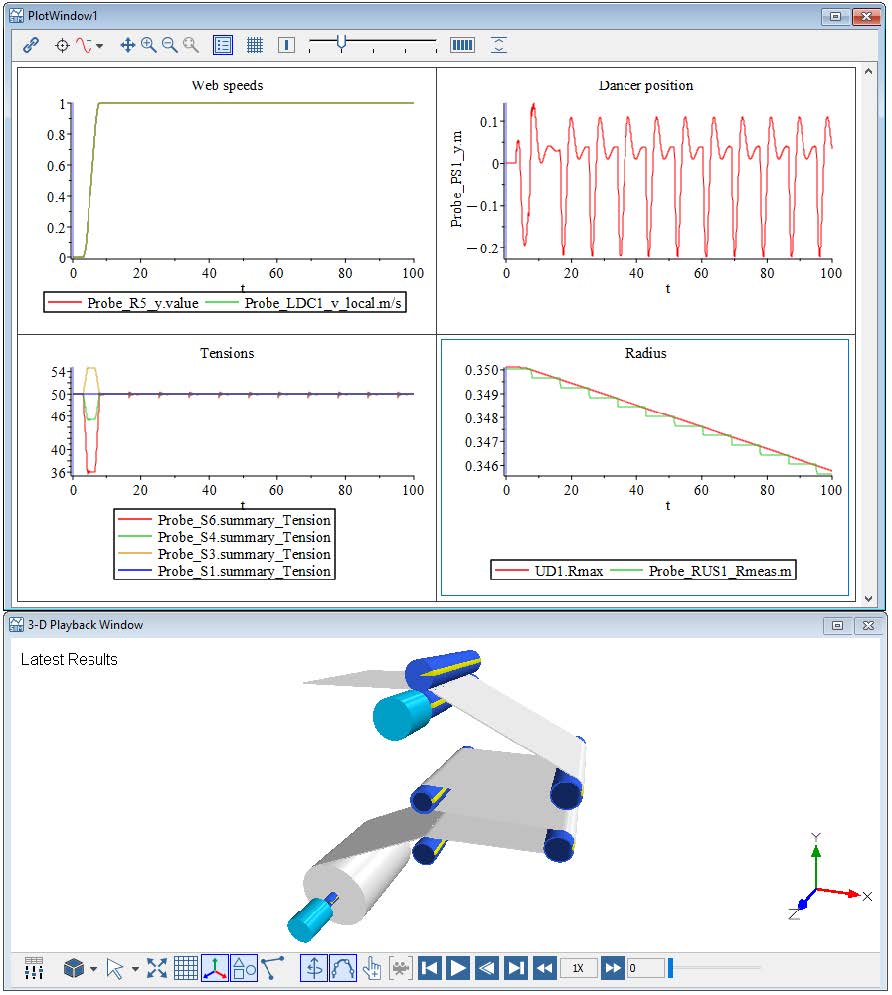

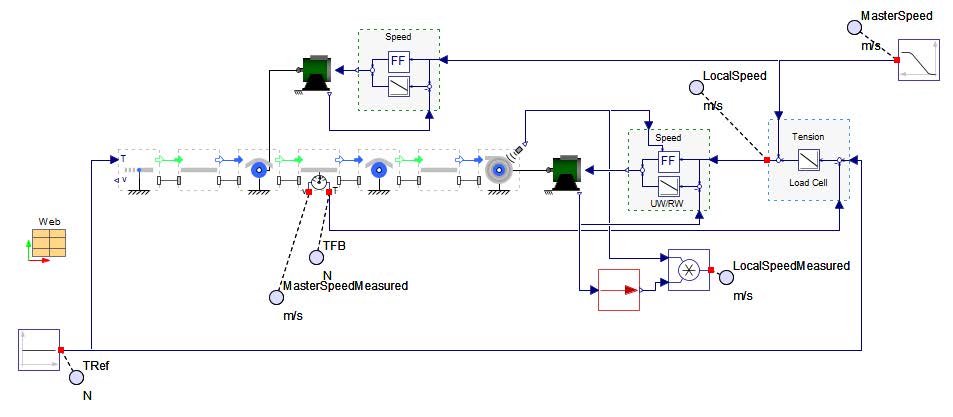

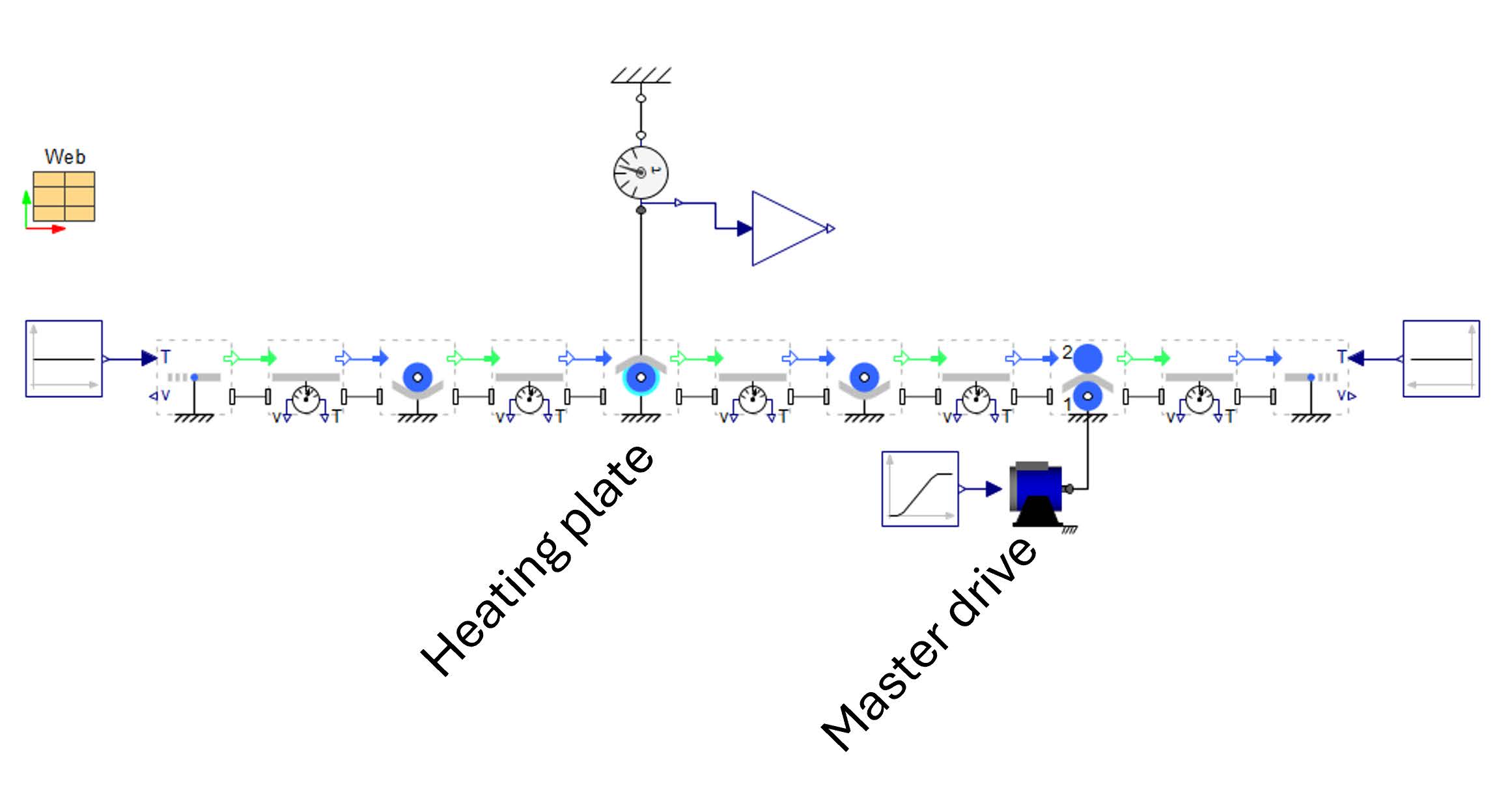

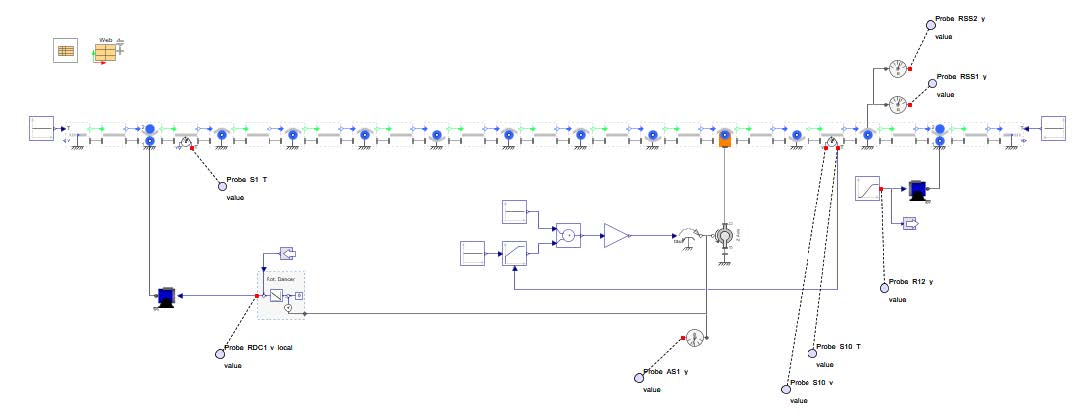

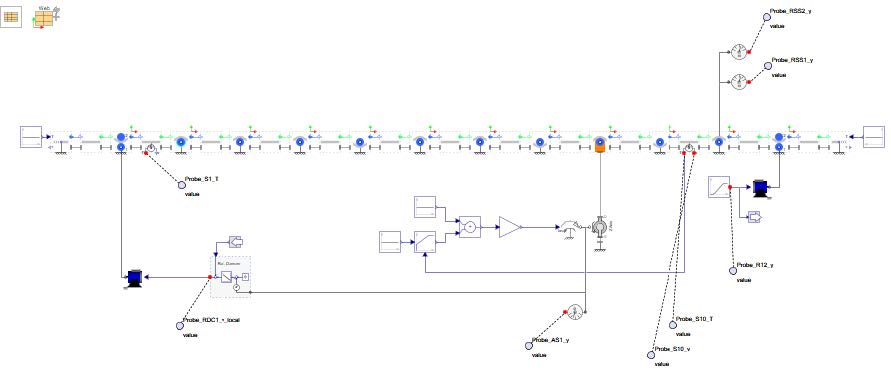

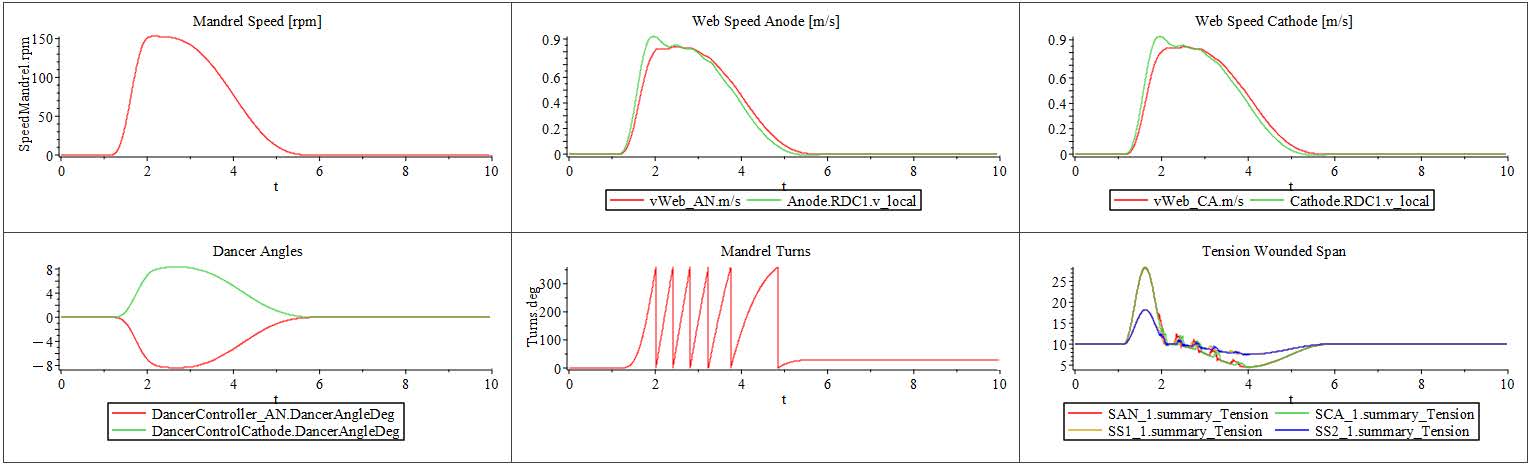

The Figure 5.1 illustrates a typical web line setup where the master web speed is defined by a master drive located on the nip roller. On the right side, the rewinder is regulated based on tension measurements, while the unwinder is controlled using feedback from the angular position of a dancer.

Figure 5.1: Control structure of a web line

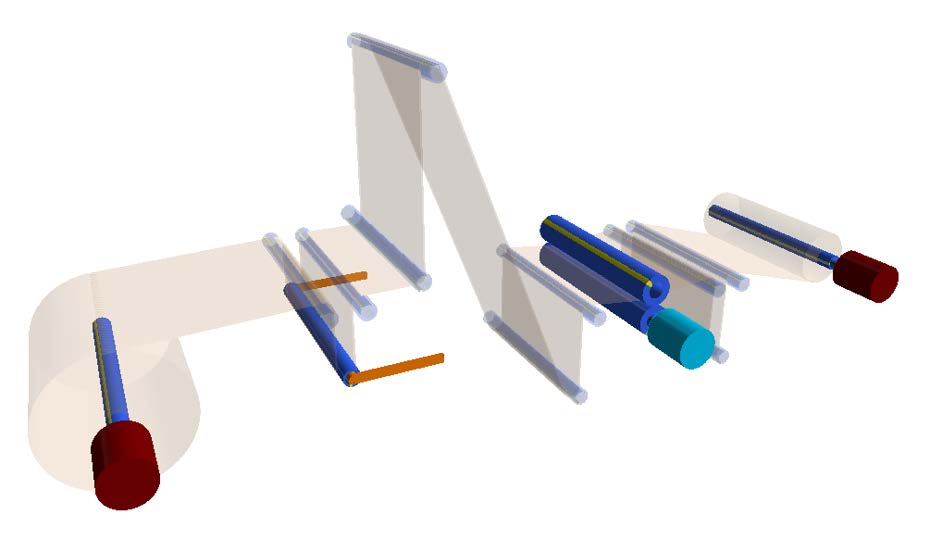

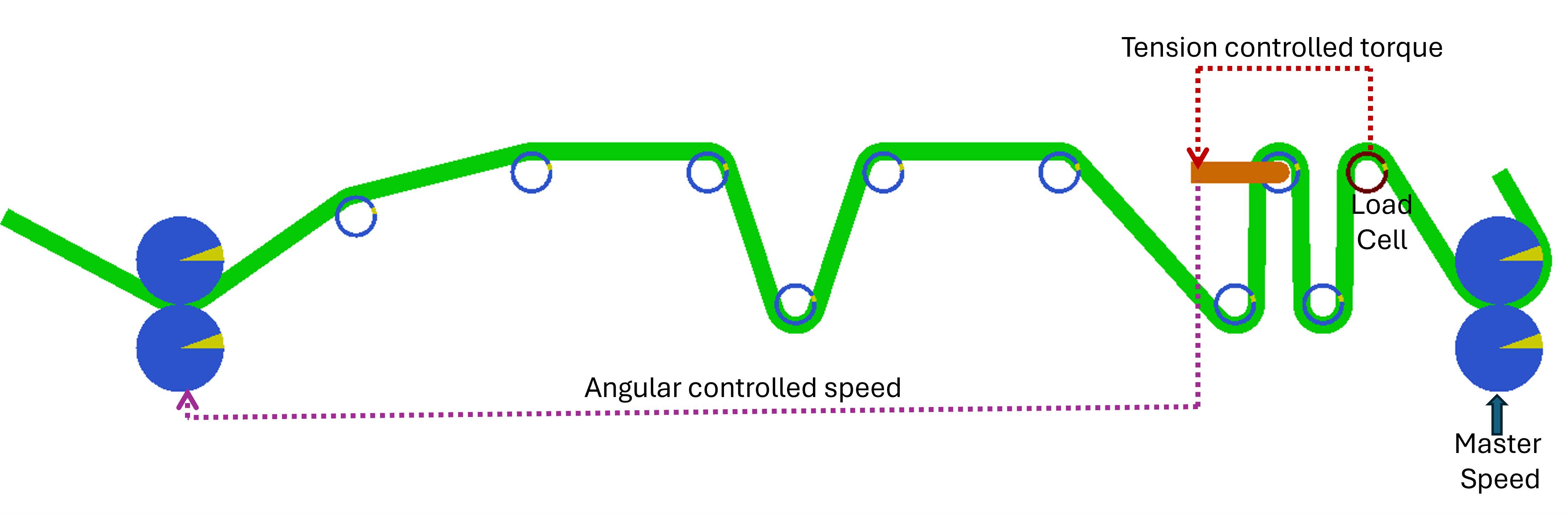

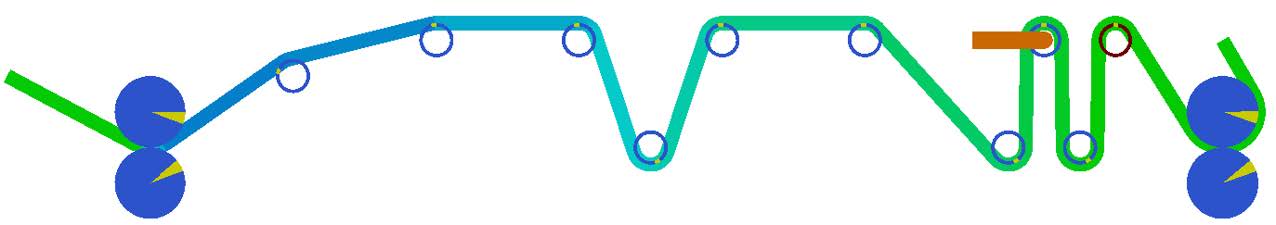

The Drives components can also be visualized from MapleSim’s 3D viewer as well. The Figure 5.2 displays a 3D representation of the example shown above.

Figure 5.2: 3D view of the web line

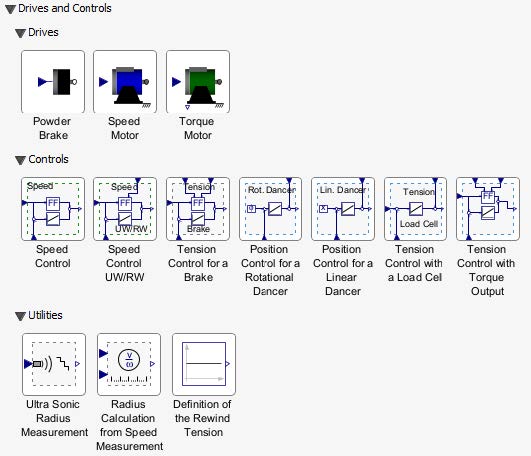

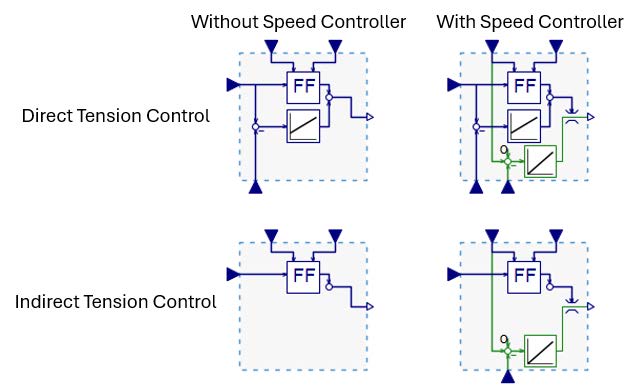

The Web Handling: Drives and Controls sub library has two categories as shown in Figure 5.3. The Drives section includes a brake component designed to model a powder brake, along with two distinct drive implementation options. In the Controls section, users can find various components dedicated to both tension and speed control. These components offer flexibility in defining the units for each input and output signal. By default, the units are set to SI standards—torque (Nm), tension (N), radius (m), and web speed (m/s), with rotational speeds specified in revolutions per minute (rpm).

Figure 5.3: Components of the sub library Drives and Controls

All components can be visualized within the 3-D Workspace and 3-D Playback Window, allowing users to view the physical arrangement of elements within the R2R web line and to illustrate the defined tension zones. While optional, this visualization feature enhances the understanding and analysis of the R2R system layout. For accurate representation, the x-y coordinates of the motor position, as well as parameters such as roller length, motor length, and motor diameter, must be specified. Additionally, users can customize the color of components for clearer differentiation and visual clarity.

The Powder Brake component represents a simplified model of a brake system, typically used along with an Unwind Drum to generate tension in the web. This component requires a specified torque input at the tau port, which can be supplied via a reference signal or through an external control loop, such as a tension controller. The model also includes an internal inertia to represent the physical characteristics of the brake mechanism.